Overview

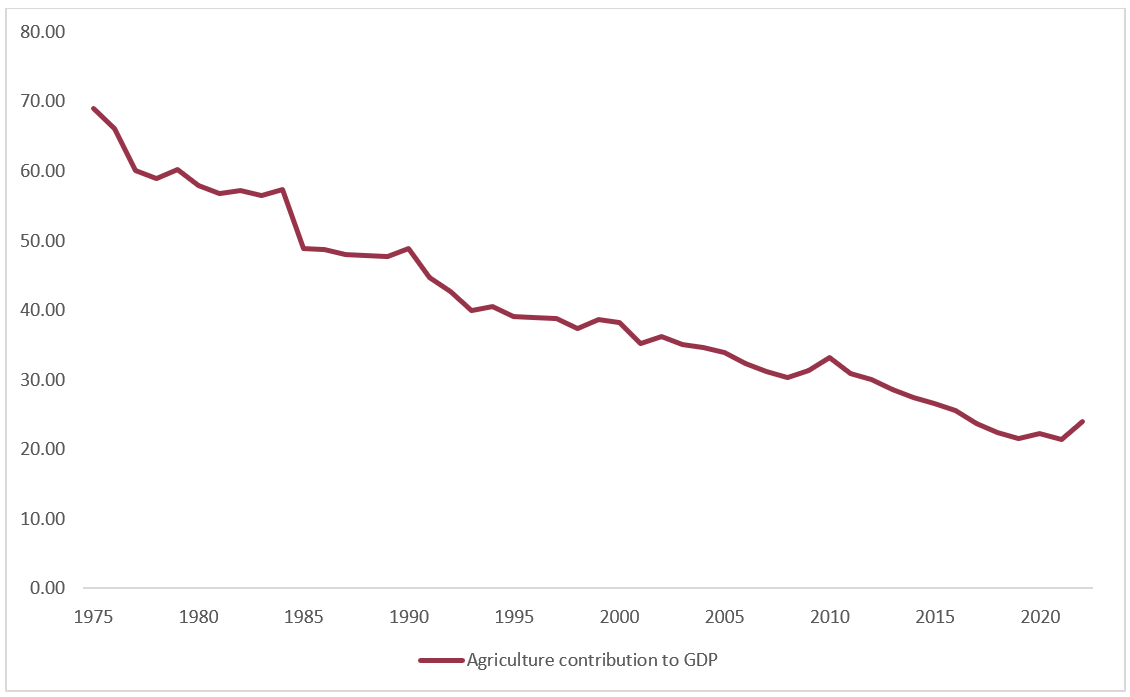

The agriculture sector in Nepal plays a vital role in the country’s economy, providing employment opportunities and contributing significantly to the country’s GDP. In 1975, the agriculture industry in Nepal accounted for 65% of the country’s GDP. However, the world’s focus shifted from agriculture to manufacturing, and Nepal’s economy too underwent structural changes, resulting in a decrease in the agriculture sector’s contribution to GDP. By 2000, the agriculture industry accounted for roughly 40% of GDP, while the manufacturing sector grew from 4% in 1975 to 9% by 2000. In 2022, the agriculture sector’s contribution to GDP stood at 23.95%, whereas the manufacturing sector contributed 14.3% to GDP. In the year 2000, approximately 75% of the total population in Nepal relied on the agricultural sector for their livelihood then, by 2022 it decreased to 66%. The shift in focus from agriculture to services, such as real estate, was driven by remittance-fueled investment in the construction industry. This trend is not unique to Nepal, many developing South Asian economies are witnessing a decrease in the agriculture sector’s share of GDP and a corresponding increase in the services sector. Countries such as India, Nepal, Indonesia, and Malaysia are experiencing faster annual growth rates in the services sector compared to the industry.

Figure 1: Agriculture Contribution to GDP

Source: World Bank data, Agriculture Sector Contribution to GDP (1975-2022)

Bottlenecks in the Agriculture Sector

Nepal’s agriculture sector has undergone significant changes over the past decade with the introduction of supportive government policies, a shift from subsistence farming to commercial farming, and the adoption of new technologies. However, despite these positive developments, the sector continues to face various limitations and issues. This article will discuss some of the bottlenecks that hinder the growth and potential of Nepal’s agriculture sector.

1. Land Fragmentation: The nature of agricultural practices makes them vulnerable to changes in land reforms. Land fragmentation owing to changing land reforms has negative impacts on agricultural productivity – reducing the economic opportunities available to farmers. The reduced arable plot sizes are a result of inheritance laws that make the landholdings small and limiting to profitable agricultural practices. Population growth is directly related to inheritance. People wish to acquire a parcel of land not only for agricultural activities but for investment, enhancing personal prestige & status, and also for the future of their family. Dividing the land into parcels has caused the issue of land fragmentation and small land holdings. Small landholdings typically only produce enough food for the farmer and their family to survive, and the farmer would then need to invest in the necessary infrastructure to sell any surplus. Unfortunately, the returns on such investments are often insufficient causing losses to small landholders. Along with that, land fragmentation is one of the major causes of soil erosion and degrades the quality of the soil.

2. Inadequate Infrastructure development: Agriculture is a complex practice and its development rests on infrastructure development by supporting allied sectors. Nepal’s current state of infrastructure is not suitable to favor the massive commercialization of agriculture. Out of the 2.60 million hectares (ha) of land under cultivation, 1.80 million ha is irrigated, of which 1.40 million ha lies on the Terai or plains, and the remaining 0.40 million ha of land remains unirrigated, usually dependent on the seasonal rains. Additionally, Nepal has made progress in developing storage facilities for agricultural goods – there is only 35 cold storage running in Nepal with a capacity of 3000 metric tons per cold storage, which isn’t enough. The physical infrastructures that support market transactions, such as haat bazaars and collection centers, are scarce or nonexistent in rural areas, and their connections to metropolitan market hubs are shaky. There are only 210 Krishak Baazar at the moment in Nepal, and because of this farmers still prefer the informal markets to sell their products. There’s only one accredited laboratory in Kathmandu, the National Food and Feed Reference Laboratory which was established in 1961 AD as the Department of Food. Nepal does not have the sound basic infrastructure for favoring the commercialization of agriculture massively, though it has been developing at a slow pace.

3. Traditional Farming: Agriculture still relies mostly on subsistence farming—less than 10% of farm holdings sell their produce in markets. About 66% of the population is dependent on agriculture, among them, the two-thirds agriculture-dependent population is pursuing subsistence farming. The majority of farmers in Nepal continue to use traditional farming techniques, such as using livestock to clear land, livestock waste as manure, old seeds, and local labor. Due to a lack of modern farming methods, about 25% of the land remains uncultivated. While quality seeds alone can increase agricultural production by 15%–20%, most farmers in Nepal use locally available seeds retained from previous cropping seasons because of poor penetration of formal seed markets in rural areas, inadequate seed multiplication, and the lower cost of locally available seeds, resulting in less than 10% of farmers currently purchasing seeds for major cereal crops.

4. Limited access to Education and training: Agricultural education in Nepal is going through rapid expansion, but the focus has been on numbers and not quality. Currently, 20 colleges offer BSc in Agriculture, BSc in Horticulture, and BSc in Tea Science programs with an annual intake of just over 1,100 students. The country produces many agriculture graduates annually, but few become technical consultants or set up agriculture enterprises. The Ministry of Agriculture and Development (MOAD) has 378 extension offices nationwide and each office serves more than 11,000 farmers; one technician is responsible for an average of 1,500 farmers, whereas in developed countries this ratio is 1 technician per 400 farmers. Academic curricula in Nepal need to be constantly updated to address the current needs and challenges of agriculture, as technical knowledge is changing rapidly. However, many curricula developed decades ago remain largely the same and are more theory-based and lacking in diverse alternatives, making them inappropriate for agricultural communities in diverse geographical and agroecological regions.

Way forward

The agriculture sector in Nepal has tremendous potential for growth and development. However, it faces multiple challenges, such as land plotting, inadequate infrastructure, limited market access, and lack of modern technology. To address these issues, the government, private sector, and international donors must collaborate to increase investment in the agriculture sector. Prioritizing financial and technical support to help farmers adopt modern farming practices is very crucial.

One of the key areas of focus should be on improving and expanding irrigation systems, particularly in regions with seasonal rainfall. Doing so will increase crop yields and reduce dependence on rain-fed agriculture. Additionally, research and development should be prioritized to identify suitable crops, develop better varieties, and enhance agricultural techniques. The adoption of modern technologies such as precision agriculture, mechanization, and information and communication technologies (ICT) can improve productivity, reduce labor, and improve quality.

The government can also create policies and regulations that promote exports and trade, which will further boost the agriculture sector. Finally, it is essential to encourage young people to take up farming by providing training, education, and financial incentives. Overall, transforming the agriculture sector of Nepal requires a multi-pronged approach that involves investment, research, modernization, market access, and youth participation.

Kaatya Mishra is a BBA graduate with a major in Finance from the Kathmandu College of Management. Her interests lie in economic development, poverty alleviation and public policy. She is currently working as a fellow at NEF.