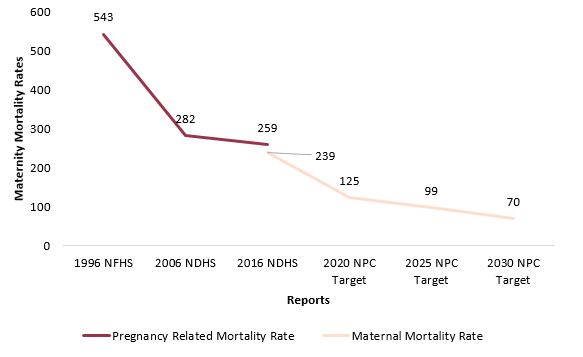

Despite significant efforts, maternal mortality remains a global challenge. In 2017, an estimated 295,000 women died from pregnancy-related causes worldwide, with a maternal mortality ratio (MMR) of 211 deaths per 100,000 live births. The vast majority of these deaths are preventable with access to proper healthcare services. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 3 on “Good Health and Well Being” aims to reduce the number of MMR to less than 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030 globally, with no country exceeding 140 deaths per 100,000 births.

Figure 1: Maternal Mortality: Progress Made and Targets

Source: The national population and housing census 2021

Nepal has set an ambitious target to reduce maternal mortality deaths to 116 per 100,000 births by 2022 and then even lower to 99 by 2025. However, in 2021, 653 women died of pregnancy-related deaths, of which 622 were classified as maternal deaths. This put the MMR at 151 per 100,000 live births. Given such high numbers, achieving this goal within that timeframe may be difficult. Moreover, Nepal faces major challenges due to insufficient access to proper healthcare facilities in rural areas, contributing to the challenges in realizing this goal. Moreover, the lack of awareness about maternal health leads to the underutilization of services even if they are accessible. This is reflected in the case of Banke district, Lumbini, which has seen 83 pregnancy related deaths over the past three years. This breaks down to 35 deaths in 2019-20, 41 in 2020-21, and 7 in the year 2022. The leading cause of death among new mothers was anemia, which is avoidable if the women receive proper pre- and post-natal care. However, many women skip checkups, especially in rural areas.

Cost-effectiveness Analysis for Better Decisions

By analyzing the costs of different tools aimed to reduce maternal mortality, health economics can guide policymakers in making the most impactful decisions. The methods like cost-benefit, cost-effectiveness, and cost-utility analyses could be used to expand access to skilled birth attendants, improve prenatal care, and build accessible emergency facilities. The cost to reduce maternal deaths and the associated financial burdens these deaths cause could be compared. This information helps policymakers in two key ways. First, it addresses what to focus on first. Particularly, should they spend more money on training birth helpers or making checkups easier to get to? Secondly, it looks at how to spend the limited budget. Specifically, how to create the biggest positive impact in saving the mothers’ lives using the resources.

While hospitals have been instrumental in reducing pregnancy related deaths, a new challenge arises as more women in rural areas deliver without getting the proper access to maternal care. Simply having a hospital birth isn’t enough. Some reasons why women in rural areas utilize the services less frequently is due to potential barriers which include the distance to hospitals, lack of transportation, and inadequate accommodations for mothers and their families. Additionally, shortages of equipment, medicine, and staff, along with the prevalence of informal payments and a growing private sector with a weak public health insurance system and high cost, could all be significant factors deterring poor women from seeking reproductive health services. Nepal faces unique challenges like geographic disparities in MMR and limited access to quality healthcare in rural areas. Rural hospitals struggle to provide timely care due to a shortage of skilled staff and equipment. This forces them to refer pregnant women to larger city hospitals, often causing delays in critical medical interventions. Tragically, some women in need of urgent care are airlifted to city hospitals only after complications arise at the local level. However, this is still time-consuming and sometimes such delays can be fatal. To address the regional differences in Nepal, inclusive infrastructure development is vital to improve access to emergency care and addressing social barriers that hinder healthcare access.

Social deterrents such as a lack of faith in public health facilities is common throughout the country especially during COVID-19 pandemic many pregnant women and mothers who gave birth lost their lives which could have been prevented with better public awareness campaigns. The reason for this was, fearing infection at hospitals, many women gave birth at home, lacking access to the timely medical care they desperately needed. Addressing these issues is crucial to ensure all women, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds, have access to the quality care they deserve. Policy makers could ensure birth preparedness, financial incentives, free delivery services and community post-partum care programs in local wards in districts.

Nepal’s Specific Considerations

Nepal’s constitution guarantees women the right to safe childbirth and healthcare related to reproduction. To make sure these rights are met, the Safe Motherhood and Reproductive Rights Act was passed in 2018. This law focuses on ensuring healthcare services for safe childbirth are high quality and easily accessible to women. According to the Ministry of Health and Population, Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2022, there’s been good progress in getting women to deliver babies in healthcare facilities all over Nepal. The number has jumped from 57% in 2016 to 79% in 2022. However, there’s still a gap, with 19% of births happening at home because of a lack of orientation on safe delivery, postpartum and neonatal care.

According to the survey “Economic Cost Analysis of NICU in Tertiary Care Centers in Nepal”, the Ministry’s Neonatal Treatment Package fails to cover health facilities. The hospitals might spend over NPR 33,000 to help the newborn children at a neonatal intensive care, but the government only provides them with NPR 8,000. This makes it hard for hospitals to offer free care, and the families end up facing the burden of costs for hospitalization, medications, and potential newborn care. This could put low-income families in a precarious position of needing to choose between a difficult financial position and proper healthcare, if not making the required care completely inaccessible due to costs.

Outlook

Unattended maternal mortality can lead to a cascade of negative consequences because healthy mothers raise healthy children, creating a ripple effect of well-being throughout households, communities, and the entire nation. If families lose their mothers, communities lose their vital members, and the nation loses its potential. By prioritizing maternal health, Nepal invests not just in saving lives, but in building a stronger, healthier, and more prosperous future for all. Technology can play a crucial role in promoting a healthy Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR) in Nepal. The “Mero Poshan Sathi” mobile app launched by the Ministry of Health and Population informs mothers and babies in promoting proper antenatal, and postnatal care practices and healthy diets. This app is a prime example of empowering women with information, helping them make better choices about their health and nutrition throughout pregnancy, childbirth, and caring for young children. Saving mothers’ lives is an investment in a brighter future for Nepal.

Regina Khanal works as an intern at Nepal Economic Forum (NEF). She holds a bachelor's degree in Business administration (with specialization in international business and digital marketing). Her interests range from academia to social work. She aspires to excel in economic domains that actively contribute to the welfare of the community, driven by her keen interest in economics.