Nepal has a sizeable working-age population between the ages of 15 and 64 that represents 65% of the total population. This population dynamic has the potential to transform the economy in what economists call a demographic dividend. This concept refers to the potential economic benefits when a country’s working-age population, defined globally as people aged between 15 and 64 years, outnumbers the non-working-age population.

According to the UN estimates, although the share of the working-age population will continue to rise in the next two decades, the share of the population aged 15–24 will gradually decline with an increase in the population aged 65 and above. This shift can impact the window for a demographic dividend in the absence of relevant policies supporting education, health, and opportunity that support societies navigate this demographic transition to positive end outcomes. As the proportion of the working age population is forecast to peak at 70% in 2048, followed by a gradual decline, the window of opportunity in parallel diminishes.

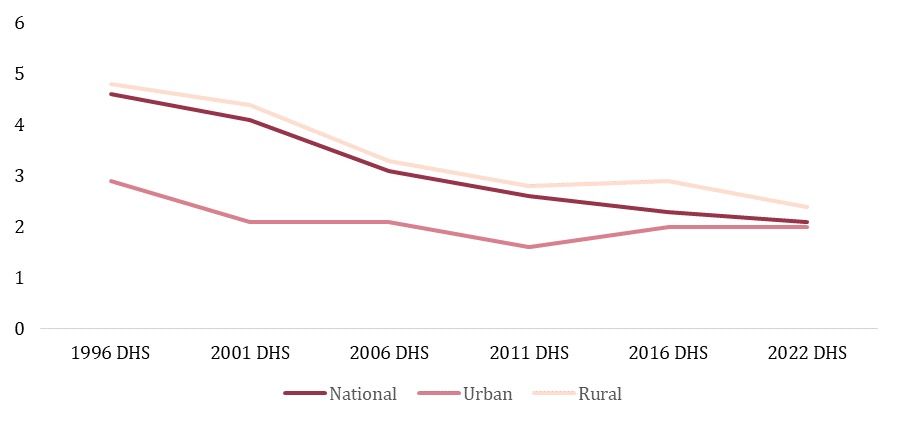

These projections also point to another associated population trend that relates to population ageing. As the share of the working-age population gradually declines, the proportion of the elderly population aged 65 and above increases. Nepal will reach this position in 2024, with the elderly population representing a 7% share of the overall population and “aged status” by 2058 with 14% share. This phenomenon is compounded by the overseas migration of youths as well as declining fertility rates that have dropped from 4.6 children per woman in 1996 to 2.1 in 2022, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Total fertility rate (1996 to 2022)

Source: Nepal Demographic and Health Survey

A Policy Challenge of our Times

This trend of ageing populations and declining fertility is impacting a growing number of countries where the growth of the proportion of elderly is outstripping the number of births and new younger generations. This is now a common population trend across the globe, not only in the OECD countries, as has historically been the case since the 1960s. Today, approximately 50% of the global population lives in countries where fertility levels have fallen below the replacement threshold. These countries all have important policy choices to make.

These policy decisions must consider the impact of these changes on a range of government services, the economy, and public finances that are far reaching as population dynamics shift. They also need to be grounded in the assumption that there are a range of issues in deciding when to have a child, including financial security, the costs involved, career development for women, child care support, and the overall family policy environment. As women increasingly become a key part of the workforce and society’s priorities change, fertility becomes an ever more important public policy discussion. This can too often focus on trying to stimulate growth in birth rates by drawing on top-down incentives such as tax breaks for families with children rather than utilizing the full range of evidence-based socio-economic tools at our disposal. These generally have resulted in more successful outcomes by creating a women-friendly social environment and guaranteeing the rights of women and girls. That being said, no single country has managed to reverse this trend fully through government intervention, despite a variety of initiatives being introduced. There are many lessons to be learnt.

Three main pillars to prepare for transitions

What do we know about how best to manage this transition in our populations? Learning from case studies across the world, there are three main policy approaches for a successful transition:

- It is crucial to recognize as societies, families, and individuals, including men and women, change, it is important that at all levels policies are able to flexibly respond to the diverse needs of the lives of families and individuals. Shifts in how women and men participate in public and private spheres of life and the economy impact decisions about family life in profound ways. As women have increased access to education and opportunity, decisions about having a family are more often balanced with other considerations. Societies evolve and change rapidly, and we need to analyse and anticipate these changes to respond quickly when they occur so that policies are timely and anticipate future trends in population rather than being reactive. It is vital to be prepared for the future in terms of population dynamics.

- The most effective way to deal with concerns about the changing fertility rates is to ensure gender equality and empower young people in both spaces, public and private. There continues to be an unequal sharing of work in raising children between men and women. Creating a fairer and more equal environment for raising children as well as domestic work would start to break down these inequalities. There needs to be more investment in parental leave for both men and women, and childcare costs need to be affordable for all families. Because historically women have largely been responsible for family life, even modern workplaces are not designed in a way to accommodate the family life of women and men with children. Flexible working hours and family-friendly workplaces are all too rare, apart from in small pockets of the world. Professional life and family life need to coexist, not compete with one another. A range of financial support and social protection provided by the government for young people is also crucial for them to be able to start a family comfortably in Nepal, especially in urban areas, due to rising living costs.

- Any approach needs to be evidence-based. Today in this age of digital innovation, population data is available at unprecedented levels. Nepal is no exception. To be able to make good decisions for the future of the population, evidence needs to be available for those making decisions to make informed choices on where and how to invest financial and other resources to manage the transition to a different population dynamic that promotes rights-based decisions around fertility rather than producing rarefied policies from a top-down position that have negative outcomes, especially for women.

Concluding remarks

There is no universal solution to the issue of declining fertility. Effective policies, however, look at the issue broadly and support individuals, families and parenthood rather than focusing narrowly on fertility and childbirth. This underscores the importance of investing public spending in the health, education, and well-being of families to create a family- and child-friendly society. It is important for modern family policies to remain non-coercive and fully support individual sexual reproductive rights, allowing people to make informed reproductive decisions and provide adequate supports to help the decision. Coercive or restrictive policies are neither sustainable nor the goal. Preparing for the future now, guaranteeing every individual’s access to universal access to sexual reproductive health and rights making gender equality a reality, and using evidence are, however, keys to managing a successful transition to the changes we are witnessing in population dynamics across the globe.

Won Young Hong has served as the UNFPA Country Representative for Nepal since 11 July 2022. With over 16 years of experience in international development, her expertise spans policy analysis, public administration reform, institutional capacity development, data, and youth empowerment. A national of the Republic of South Korea, Ms. Hong holds a Master in Public Policy from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.