One of the oldest routes between Nepal and China, the Korala border exemplifies the evolving relationship between the two countries. Once an open border bustling with nomads, trade, and cultural exchanges, it has transformed into a regulated border that underscores the disparities between Nepal and its northern neighbor. But how did this transformation take place and what is the situation of the border today? Drawing on research and insights from NEF’s recent field visit as part of our Nepal-China study, this article seeks to answer these questions.

From Open to Institutionalized: The Impact of the Mustang Incident

Located 30 kms from Lo Manthang, at an altitude of 4,650 m, the Korala border was not always as rigidly defined as it is today. Prior to 1962, the Mar-Khog Chorten, situated around 2.5 km south of the modern border marker no. 24, was used as the traditional boundary between Nepal and China – primarily as a landmark for regional trade. Even in modern times, the chorten’s historical significance persisted as Chinese authorities delivered substantial humanitarian aid post the 2015 earthquake there.

Traditionally, the region maintained an open border, allowing nomads, livestock, and traders to move freely across it. A monk from Chode Gompa shared stories of Tibetan nomads visiting monasteries in Lo Manthang around 20-25 years ago, and even royal ties linked the two regions, as evidenced by Mustang’s queens often originating from Tibet. However, with the Chinese occupation of Tibet in the 1950s and the subsequent solidified presence of the modern nation-state, everything changed.

What particularly accelerated this institutionalization of the Korala border was the Mustang Incident of 1960. Amidst the build-up of Tibetan troops and an increasing influx of refugees in Mustang, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) intensified its patrols along the Nepal-China border. On June 28, a PLA patrol encountered a contingent of Nepali officials and troops in what they identified as Chinese territory (near the aforementioned Mar-Khog Chorten) and opened fire. This event resulted in the death of Subedar Bam Prasad and the capture of 15 Nepali soldiers. Following high-level talks and extensive reporting by international media, China issued an apology and acknowledged its trespass. This incident triggered the 1961 boundary treaty and the 1963 ‘Nepal-China Boundary Protocol,’ which formally solidified the border as we know it today. The 1963 protocol was particularly important as it established 79 border markers along the 1,111 km-long border and abolished trans-frontier cultivation and pasturing, thereby erasing the fluidity of the boundary.

Korala as a Politically Sensitive Region

Prior to the Chinese occupation of Tibet, Mustang was a peripheral area for the Nepali state, valued primarily only due to the lucrative trans-Himalayan salt trade which later diminished due to the spread of subsidized iodized Indian salt. However, following the occupation, particularly after the Mustang Incident of 1960, the Korala region emerged as a point of strategic concern for both Kathmandu and Beijing. Despite the closure of the border due to political sensitivities, the region became a haven for many Tibetan refugees fleeing across the border. In 1960, Mustang also became the primary base for the CIA-funded Tibetan resistance movement – the Chushi Gandrung Army or, more commonly known as the Khampa Rebellion. While the rebellion ended in 1972, Mustang remained a geopolitically sensitive and restricted area.

This sensitivity was highlighted as recently as 1999 when the 17th Gyalwa Karmapa, one of Tibet’s most important spiritual leaders, used the Korala border to escape to India. Within a year of his escape, China constructed a border fence, further solidifying the territorial demarcation. Once again, political sensitivities triggered a magnified state presence, transforming the border from a historically fluid boundary into the rigid, institutionalized border we see today.

Tsongras and the Movement of Trade from Barter to Cash

The solidified state presence and China’s subsequent dominance in the region is perhaps most exemplified by the evolution of trade through tsongras. Originally, a tsongra was a semi-annual trade fair held for several weeks every spring and fall, where Nepalis and Tibetans gathered not only to trade but also to socialize, drink, and gamble. Until 2007-08, the location of the tsongra alternated between Nyechung in Mustang and Likse in Tibet, based on an agreement between the King of Mustang and Chinese officials. However, with the construction of a motorable road through Korala, tsongras shifted from fixed locations to mobile fairs near population centers in Mustang. Many locals viewed this as a deliberate move by China to promote dependency on Chinese goods. For this, they cite the fact that Chinese goods have flooded shops in Mustang today – a reality that even led to the Government of Nepal impose tariffs on tsongra purchases in 2014.

As highlighted in Galen Murton’s research, tsongras also reflected the changes in the region through the movement of trade from barter to cash. Until the 1950s and 60s, trade between Mustang and Tibet relied largely on barter. Even into the early 2000s, exchanges were often conducted in kind, with one animal—a goat, sheep, or chyangra (mountain goat)—equivalent to a pair of Nepali-made Gold Star sneakers. This is particularly astonishing in today’s context as now, a singular chyangra costs around NPR 30,000 to 40,000 each. However, the advent of better roads, increased purchasing power driven by tourism and remittance income, and an appetite for cheap, manufactured Chinese goods, gradually shifted trade dynamics. Cash became the primary medium of exchange, symbolizing yet another step towards the region’s integration into the modern nation-state.

Figure 1. The Chinese concrete structures (on the right) and Nepali tents (on the left)

Source: Chandani Thapa

Korala Today: A Representation of Unequal Power Dynamics between Nepal and China

Today, the Korala border starkly illustrates the power asymmetry between Nepal and China, visibly marked by the contrast between the imposing concrete structures on the Chinese side and the modest tents on the Nepali side, as seen in Figure 1. Reopened in late 2023 following a closure due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Chinese side boasts essential infrastructure including customs facilities, quarantine areas, accommodations, a laboratory to check goods coming across the border, and truck parking – all hidden behind the concrete façade. In contrast, during our visit to the border in early October 2024, the Nepali side featured only 10-15 tents occupied by Nepali merchants selling Chinese products, with no visible security or supporting infrastructure.

On October 30, 2024, a Nepali immigration office at the border was inaugurated by Home Minister Ramesh Lekhak. A prefabricated 10-room post equipped with electricity and mobile phone connectivity, the immigration office is Nepal’s attempt to make this border a fully operational one like the one at Rasuwagadhi. However, within just a week of its opening, the office was shut down due to freezing temperatures, a lack of amenities, and delays in deploying staff.

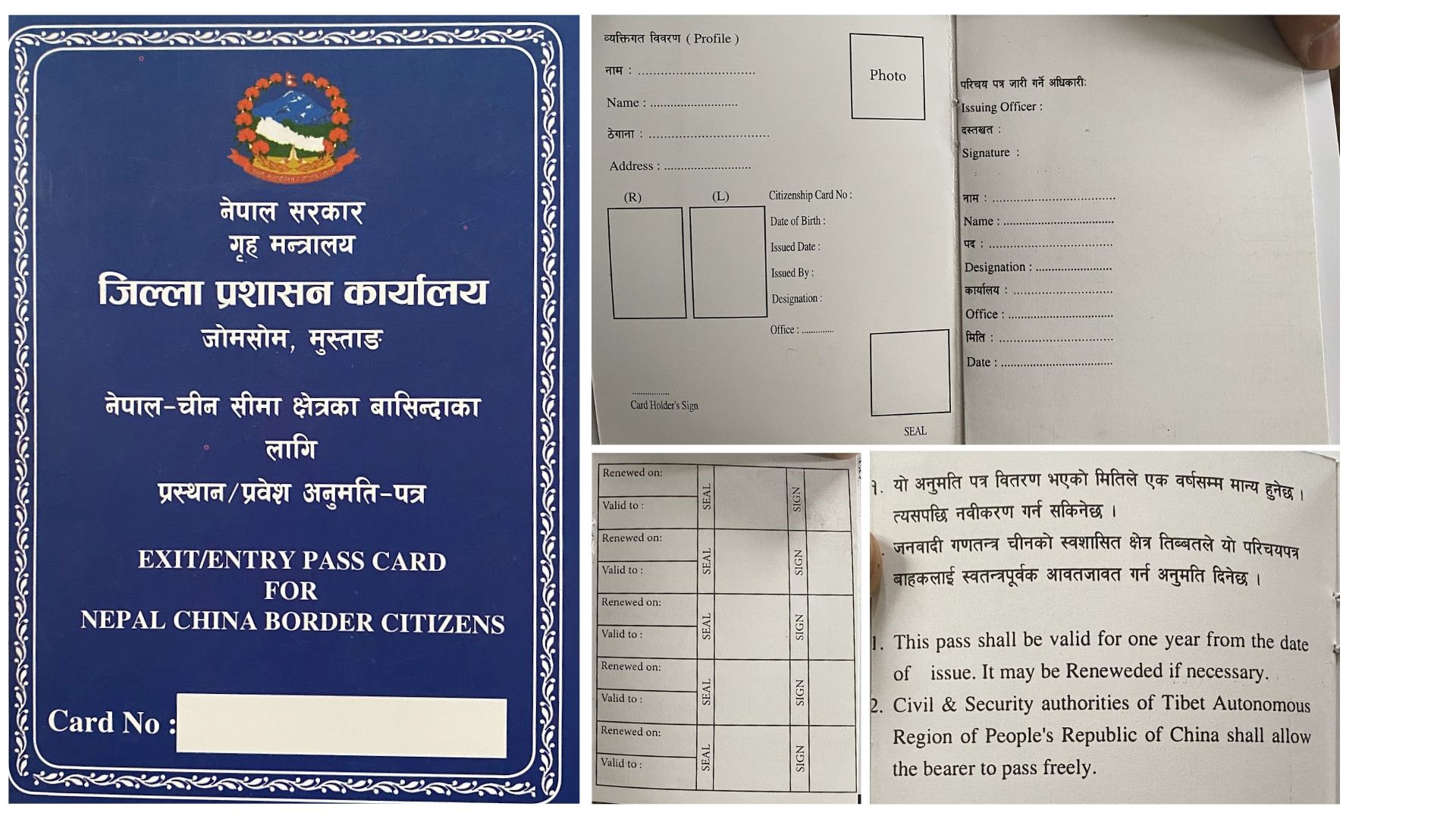

The power asymmetry between Nepal and China is also evident in border-crossing dynamics and the differing experiences of those who traverse it. As part of a 2023 agreement that reopened the border, residents from Mustang’s northernmost municipalities—Lomanthang and Lo-Ghekar– were granted permission to cross into China for trading purposes for designated hours using an annual permit issued by Mustang’s District Administration Office (Figure 2). Later that year, the policy was extended to all residents of Mustang. However, many residents we spoke to did not know about this recent development.

Figure 2. Exit / Entry Pass Card for Nepal China Border Citizens

Source: Author

Our conversations with locals from the area revealed many insights, once again highlighting the inequality between Nepal and China at the Korala border. Firstly, while many Nepalis cross the border to trade, it is very rare for Chinese individuals to come through the border; they trade only on their side of the border. Secondly, border security for Nepalis is extremely stringent. Permit holders are allowed to cross only at 9 a.m. and have to leave by 2 p.m., during which they must submit biometrics (fingerprints and Iris scans), pass goods through an X-ray machine, and ensure they are not carrying items deemed sensitive including images of Dalai Lama or Tibetan religious beads. Despite these challenges, many locals make this journey regularly, pooling resources to hire a jeep at a shared cost of NPR 15,000, as buying goods from Tibet remains cheaper due to the minimal custom duties levied much by Nepali authorities. Nepali traders bring back a variety of goods, including Chinese chocolates, electronics, chyangras, beer, juice, carpets, whiskey, wine, biscuits, cup noodles, bikes, thermoses and more. In contrast, locals reported that the Chinese at the marketplace mostly just buy Nepali instant noodles, chiura (beaten rice), rice, corn flour, and maida (refined flour).

Figure 3. Chinese goods sold at the border and in tea shops in Mustang

Source: NEF team in Mustang

Conclusion

The Korala border has long been a vital crossing between Nepal and China, as evidenced by robust trade and geopolitically significant events. However, its evolution from a fluid frontier to an institutionalized boundary, starkly underscores the inequalities between the two neighboring countries. Despite these challenges, Korala holds immense potential to be more than just a symbol of disparity. Situated as one of the lowest motorable crossings connecting the Tibetan and Indo-Gangetic plateaus, it has the capacity to become a crucial link between not only Nepal and China but also China and India through the Kaligandaki Corridor and the Siddhartha Highway. While China seems to be prepared for this possibility due to their extensive infrastructure at the border, it is Nepal that must take this as an opportunity to assert its agency and recalibrate ties with its northern neighbor. As a start, at the very least, it must take measures to improve the condition of the immigration office at the border.

Suyasha Shakya holds a Bachelor's degree in Economics (Honors) from Ashoka University along with minors in International Relations and China Studies. Prior to joining Nepal Economic Forum, she worked as an intern at the Rwanda Development Board (RDB). Given her thesis on 'The Impact of Nepali Migration on Nepali Identity', she is interested in migration, public policy, and governance.