On July 8, 2025, a devastating flood at the Rasuwagadhi border killed 11 people, left 18 missing, and washed away the Nepal-China Miteri Bridge, a major trade link between the two countries. The disaster also exposed something less visible but equally important: the limited nature of Nepal’s land connectivity with China—and how little this reality is understood by most.

Nepal shares a 1,414 km border with China, as per a treaty signed in 1961. Due to a variety of geographic and geopolitical reasons, however, the northern border is far less utilized and familiar to the general public than the open southern border with India. Officially, as per an agreement in 2024 between the two countries, 14 traditional border points were reopened between Nepal and China, but only six currently serve as key trade points. Of these, only two are significant for trade and travel, namely Rasuwagadhi and Tatopani. Unfortunately, the lack of an official, up-to-date source on the border, makes it difficult to track the oft-changing status of these border points, further contributing to the limited knowledge about them.

If Nepal is to strengthen its relations with China, it must first establish a clearer understanding of its existing connections and how we can improve them. Today, much of what we know about the border comes, not from the government, but from the painstaking work of researchers like Buddhi Narayan Shrestha, Amish Mulmi, Galen Murton, Sam Cowan, and Samar SJB Rana. However, while their research and writing have shaped our understanding of the border and its complexities, the insights are scattered across various sources. This article is an attempt to build on that foundation and provide a clear, up-to-date guide on Nepal-China border points that we will aim to update according to changes at the border.

Historical Context of the Modern Border

The demarcation of the modern border between Nepal and China began with the 1960 Sino-Nepal Boundary Agreement. According to the agreement, the traditional customary line between Nepal and Tibet was agreed as the basis for a boundary treaty, and a Nepal-China Joint Boundary Committee was established to delineate the entire border. Following surveys and field trips by the committee, a Boundary Treaty was finalized in 1961 with most disputes resolved through mutual cooperation by 1962. This led to the signing of the 1963 Border Protocol which finalized the border demarcation and was renewed three more times.

While the two countries had multiple traditional border points following the agreements, these were largely geographically inaccessible with inadequate infrastructure. Thus, out of these border points, six ports were given priority and only two, i.e. the Tatopani and Rasuwagadhi border points, were the most-used passes due to their accessibility even during winter months. This was reflected in the agreement signed in 2012 regarding the management of ports in Nepal-China border areas. The agreement gave priority to six ports—designating three as international ports and three as bilateral ports. Despite this, until 2015, the only major trade route on the Nepal-China border was the Tatopani-Zhangmu border, where 69% of exports and a quarter of imports passed through before the 2015 Gorkha earthquake, with the rest of the trade occurring through air and sea routes.

Unfortunately, progress from the 2012 agreement came to a halt due to the 2015 earthquake that severely damaged various border points, leading to the complete closure of the Tatopani border. While this led to trade shifting to the Rasuwagadhi border, its inadequate infrastructure meant that it was unable to absorb the incoming traffic, further depleting trade with China which was already taking a hit due to the Indian blockade. Because of being the only option available, with the Tatopani border only reopening four years later in 2019, the Rasuwagadhi border gained increasing importance. It even became an international crossing point in 2017.

Regrettably, not even one year after the reopening of the Tatopani border in 2019, the Covid-19 pandemic led to the closure of borders in Rasuwagadhi and Tatopani in January and February 2020, respectively, and the closure of all borders in March 2020. While the borders intermittently reopened, cargo movement was negligible up until 2023 when the Rasuwagadhi and Tatopani borders were fully reopened in April and September, respectively. More recently, in 2024, both countries formally opened the 14 traditional border points, indicating a new chapter in Nepal-China relations.

Current Status of Border Points

Figure 1. Nepal-China Border Points

As mentioned above, there are 14 traditional border points between Nepal and China. Here is a detailed breakdown of the most recent status of these border points, as updated on August 11, 2025.

| Districts in Nepal (East to West) | County and Prefecture in China | Nepali Border Point | Chinese Border Point | Remarks | |

| A | Taplejung | Dinggye County (Tingche/ Dinjie/ Tingkye), Shigatse Prefecture | Tiptala Bhanjyang | Riwu | Tiptala border reopened on May 24, 2024, with vehicular operations starting in January 2025. Currently open only for trade, it historically operated just twice a year for limited local exchange due to poor infrastructure and transport access. |

| B | Sankhuwasabha | Dinggye County, Shigatse Prefecture | Kimathanka | Chentang | This border is open only for local trade. A road link via Kimathanka to Tibet is under development but not fully operational, with goods still often transported manually or by livestock. |

| C | Solukhumbu | Tingri County, Shigatse Prefecture | Nangpa La | Kongbure Busang | The Nangpa La Pass, a historic Silk Road trade route between Tingri and Namche Bazar, lost its official border crossing status in 2006. It was once a vital trade and refugee route but now sees limited use, with goods mostly brought in from lower valleys or flown in. |

| D | Dolakha | Tingri County, Shigatse Prefecture | Lapchi, Bigu Rural Municipality | Ramding | The Lapchi border reopened on September 30, 2023 after multiple closures. Historically, locals maintained close cross-border ties through trade, livestock grazing, and family connections despite limited road access on the Nepali side. |

| E | Sindhupalchowk | Nyalam County, Shigatse Prefecture | Tatopani Kodari | Zhangmu | The major border point till 2015, this border was fully reopened in September 2023 and is one of the border points directly connected to Kathmandu. It currently serves as a vital point for trade and tourism. In July 2025, it even served as the entryway for the import of a helicopter. |

| F | Rasuwa | Gyirong County, Shigatse Prefecture | Rasuwagadhi (Timure) | Kerung | Opened for commerce in 2014 and for foreign nationals in 2017, this is the primary route for international tourists and one of the major routes for trade between Nepal and China. However, a flash flood on July 8, 2025 swept away the bridge linking the two countries, also damaging the customs office and under-construction dry port. |

| G | Gorkha | Gyirong County, Shigatse Prefecture | Ruila Ward 1 | Ruila Duila | In Gorkha, cross-border movement primarily takes place through two key points: the Ruila border point in Chumanbri Rural Municipality-1 and the Nguila border point in Chumanbri Rural Municipality-7. The Gorkha border reopened in September 2023, and the Gorkha District Administration Office began distributing permits from October 4. Locals commonly visit the nearby Sya market (5 km away) and Jonga market (15 km away) in Tibet, which are more accessible and more affordable than Nepali markets like Arughat, where goods cost nearly three times as much. |

| Nguila Ward 7 | – | ||||

| H | Manang | Saga County, Shigatse Prefecture | Phu village, Nar Phu valley | Rigatongba | Chyakhu village is not directly on the China border; the actual crossing point lies further north near Phu village in Nar Phu valley. A border outpost is planned for Phu village (Narpha Bhumi Rural Municipality-4) to strengthen border security, while it remains the only local level in Gandaki Province yet to be connected to the road network. |

| I | Mustang | Zhongba County, Shigatse Prefecture | Korala | Nechung Lizi | Korala became the fourth Nepal-China border point to reopen since the Covid-19 pandemic forced the closure of all crossings in 2020, resuming operations on November 13, 2023, with its immigration office becoming functional from October 25, 2024. While previously the border used to open only two times in a year, currently, the border opens for those with border passes at 9 a.m. with individuals expected to return to Nepal by 2 p.m. The route via Siddhartha Highway and Kaligandaki Corridor is considered a potential trilateral trade corridor, with nearby Lizi and Pagri markets in Tibet serving as major active trade hubs. |

| J | Dolpa | Zhongba County, Shigatse Prefecture | Marim Bhanjyang | Mayung Bhanjyang / Taklakot | The Marim border reopened on May 25, 2024. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, a 15-day annual market (haat bazaar) was held on the Chinese side, but during the closure, locals faced steep prices for essential goods like rice and salt from headquarters. |

| Kyato Pass | – | Before 2020, the Yarsa trade port opened once a year for just 10 days. While China has set up temporary revenue offices at Kyato and Marimala crossings in Dolpa, Nepal’s revenue office is yet to be established. | |||

| K | Mugu | Zhongba County, Shigatse Prefecture | Nakchenangla | Hyajimar | Closed for two decades, the Nakchelangna border was once open for five months annually but is now only open for one week per year. Locals trade herbs and cheaper Chinese goods but faced high transport costs. Trade disruptions since 1959 impacted nearby villages less severely than other Nepal-China border areas. |

| L | Humla | Purang County, Ngari Prefecture | Yari Hilsa, Lapche Bhanjyang | Purang | Reopened in April 2023, Hilsa is the closest border for the Kailash Mansarovar pilgrimage. The 95 km road from Simikot to Hilsa became fully operational in July 2025. Seasonal travel restrictions for pilgrims were lifted in March 2025 for Indian citizens, allowing 546 Indian pilgrims to visit Mount Kailash between mid-March and July. |

| M | Bajhang | Purang County, Ngari Prefecture | Urai Thadodhunga | Biling Bhanjyang | The last update on the border was that it was inspected by a government team in early June, 2024 with plans to make the point fully operational by June 30. However, no updates are available since then. |

| N | Darchula | Purang County, Ngari Prefecture | Tinkar Bhanjyang, Byas Rural Municipality | Tolang Taklakot | Tinkar Bhanjyang border in Darchula, which serves as a vital link for trade between Chhangru, Tinker, and Taklakot, reopened on May 25, 2024, facilitating trade and access to Tibet. Nepali traders have a long history of engaging in traditional commerce with Taklakot, primarily trading food and clothing items during a season that spans around four and a half months. So far, China has established a security post and a dirt road in Sapu, about a 30-minute distance from the Tinkerbhanjyang border pillar, where Nepali traders are required to have their goods inspected before entering Taklakot. On the Nepali side, a Border Outpost (BOP) of the Armed Police Force and a Nepal Police station are based in Chhiyalek, Byas-1. The Government of Nepal has also almost completed the Mahakali corridor, a tri-nation corridor that will connect India to Nepal’s Pillar No. 1, greatly shortening the route for the Kailash Mansarovar pilgrimage. |

| The six significant border points (international ports and bilateral ports) | |||||

| Uncertain about the feasibility and current operational status of the border point (open or closed) | |||||

Dimensions of the Border

To understand the current status of the Nepal-China border, it is important to understand its various dimensions that highlight its significance and potential. Here are some dimensions to consider:

Trade

Historically, most border points between Nepal and China were open and used for local bilateral trade with frequent trade fairs. These informal exchanges often involved agricultural products, handicrafts, livestock, and essential commodities, forming part of a long-standing socio-economic relationship between border populations. However, with increasingly solidified state presence and greater road connectivity, the traditional barter trade has moved towards the use of cash to primarily buy Chinese products.

In terms of formal trade, as mentioned earlier, the primary border points for trade via land between Nepal and China are Tatopani and Rasuwagadhi, of which Rasuwagadhi is currently incapacitated due to recent floods destroying the connecting bridge. Looking at trade by customs point, in FY 2081/82 BS (2024/25 AD), Rasuwagadhi handled the largest share of exports worth NPR 2.05 billion (USD 14.61 million) and imports of approximately NPR 85.23 billion (USD 609.02 million), accounting for about 4.72% of Nepal’s total imports. Meanwhile, Tatopani recorded imports of NPR 50.40 billion (USD 360.10 million) but showed no exports for the period, representing roughly 2.79% of national imports. As a whole, in the same financial year, Nepal imported NPR 341.10 billion (USD 2.44 billion) from China while exporting only NPR 2.63 billion (USD 18.79 million), leading to a trade deficit of NPR 338.47 billion (USD 2.42 billion), according to Customs data. Major imports from China were dominated by electronics and consumer goods; notably electric vehicles, smartphones, laptops, and air-conditioning units; followed by knitted apparel, fresh apples, garlic, footwear, and ready-made garments. On the other hand, Nepal’s principal exports to China consisted of carpets, woolen felts, household and kitchen items, tracing cloth, metal and wooden handicrafts, musical instruments, readymade garments, yarsagumba, and incense sticks.

The border points are also important in terms of trilateral connectivity between China, Nepal, and India, with various corridors such as the 362 km-long Biratnagar-Khandbari-Kimathanka road which is the shortest route linking the three countries in Eastern Nepal.

Tourism

China is one of Nepal’s largest sources of foreign tourists, with 101,879 Chinese tourists visiting the country in 2024. Yet, only a negligible fraction of this number enters Nepal through the land borders, with very few choosing to drive their own cars from the Rasuwagadhi border point. With better infrastructure and connectivity, Nepal could greatly tap into this potential market.

On the other hand, the Nepal-China border is of primary importance for pilgrimage to Kailash Mansarovar. Following the Covid-19 pandemic, Chinese authorities only allowed pilgrimage to Mansarovar for Nepalis in 2023 and Indians in June 2025, delayed due to geopolitical strains between India and China. Most pilgrims visit the site either through the Hilsa-Purang route in Western Nepal (the easiest route) or via the Rasuwagadhi border point. But the recent flood has affected this journey as well, compounded by visa processing challenges at the Chinese Embassy in Kathmandu.

Infrastructure

The Nepal-China border has often been the talk of the town due to plans of a China-Nepal railway connecting Kyirong in Tibet to Kathmandu via the Rasuwagadhi border, as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). A pre-feasibility study was conducted for this in 2018 and the geological study entered its final phase in April 2025. While the pre-feasibility study suggested that it was an extremely difficult but not impossible project, many locals have dubbed it as “kagat ko rail (paper railway) and sapana ko rail (dream railway),” alluding to the lack of belief that the project will come to fruition.

On the other hand, in July 2025, the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) and China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA) signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) regarding conducting a feasibility study for the construction of the Rasuwagadhi-Kerung cross-border transmission line. With Nepal’s target of producing 28,000 MW through hydropower and exporting 15,000 MW by 2035, the successful completion of such a project would create avenues away from dependence on India, as currently Nepal exports electricity to India and Bangladesh via Indian border points.

People

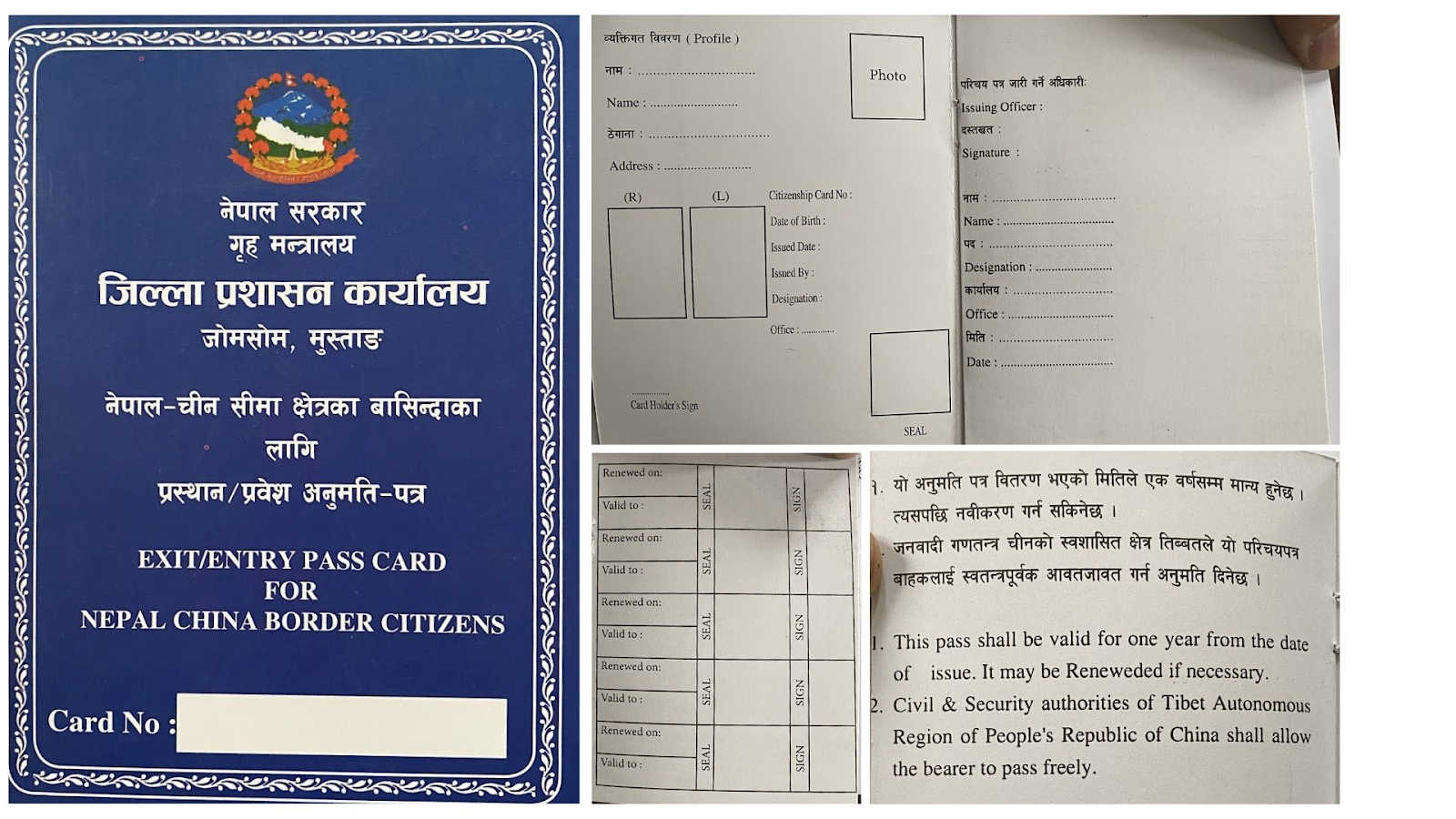

In 1981, the governments of Nepal and China signed an agreement allowing border inhabitants to continue barter trade within 30 km of the border, without being subject to formal limitations. This created the basis for an agreement in 2002 that inhabitants of bordering districts would be issued “exit-entry passes” to visit the bordering districts of the other country, without requiring other documentation such as passports or visas. Currently, with immigration offices set up in Rasuwagadhi, Korala, Hilsa, and Tatopani, many Nepalis in bordering districts cross over for trade and jobs. In our field trips to Korala and Rasuwagadhi, however, we saw varying uses of the border pass. In Korala, Nepali citizens crossed over just for daily trade, with permit holders allowed to go to China at 9 a.m. and come back by 2 p.m. Meanwhile, in Rasuwagadhi, while there were some lorry drivers and locals going for similar daily trade, we found that many locals with passes were employed in a variety of jobs, particularly in the service sector, in the bordering Chinese town of Kyirong. Most had effectively settled there, returning only to renew their passes. Many Nepalis from other districts had also transferred their location to the district of Rasuwa so that they could avail the financial benefits of such an arrangement.

Figure 2. Exit / Entry Pass Card for Nepal-China Border Citizens

Way Forward

The Nepal-China border has immense unfulfilled potential in improving relations between the two countries. While this article focuses only on consolidating updated information regarding the border points, in order to tap into this potential, three interconnected challenges must be addressed: climate, geopolitics, and infrastructure. As shown by the 2015 earthquake, the 2025 Rasuwagadhi floods, and multiple natural disasters, the Himalayan border is particularly susceptible to devastating disasters, especially in light of climate change. Thus, climate-resilient designs for infrastructure such as roads, bridges, and dry ports must be emphasized. Meanwhile, currently China largely calls the shots on the operation of the border. In order to ensure a balance in relations, steady diplomacy and updated agreements on trade, mobility, and customs should be worked on. For this, a particularly important first step would be ensuring the creation of proper immigration and customs checkpoints on the Nepali side of the border, along with better connectivity to the rest of the country. Nepal can draw lessons from mountainous border regions such as the China-Pakistan Karakoram Highway, which overcame extreme geography through sustained investment and political commitment, and the Peru-Bolivia border, where coordinated tourism and trade boosted remote economies. By making all border crossings active, investing in proper infrastructure, and practising balanced diplomacy, the border can be transformed from an underused frontier to a strategic gateway for trade, tourism, and regional integration.

Mahotsav Pradhan holds a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honors) from the University of Delhi. Prior to joining Nepal Economic Forum as a Research Fellow, he has worked as Foreign Exchange Intern at Nepal Rastra Bank. He has a keen interest in development economics, with a passion for exploring the dynamics of policy analysis and international finance. Suyasha Shakya holds a Bachelor's degree in Economics (Honors) from Ashoka University along with minors in International Relations and China Studies. Prior to joining Nepal Economic Forum, she worked as an intern at the Rwanda Development Board (RDB). Given her thesis on 'The Impact of Nepali Migration on Nepali Identity', she is interested in migration, public policy, and governance.