Nepal’s development story has long been shaped by external financing through both foreign aid and foreign direct investment (FDI). These inflows have supported roads, schools, hydropower, tourism, and manufacturing. Yet, as Nepal prepares to graduate from the Least Developed Country (LDC) status in 2026, the question of how the country can sustain growth beyond concessional aid has become increasingly relevant. This brief provides an overview of foreign aid and FDI in Nepal, their different roles in shaping the country’s economy, and what LDC graduation means for their future.

Foreign Aid: A Foundation of Development

Foreign aid, often referred to as official development assistance (ODA) refers to concessional financial or technical support provided by one country or multilateral agency to another for economic and social development.

Nepal began receiving foreign aid in the early 1950s, shortly after the fall of the Rana regime. The first major agreement was signed with the United States in 1951, marking the beginning of decades of donor-supported projects. India, China, Japan, and several Western countries soon followed, financing infrastructure, education, and health programs.

Over time, foreign aid became a cornerstone of Nepal’s public investment. The East-West Highway was primarily built with assistance from the United States, the United Kingdom, India, and the World Bank. Similarly, several airports, including Tribhuvan International Airport, received funding and technical support from Japan through the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). Major hydropower projects such as the Kulekhani Hydropower Plant were developed with aid from Japan, while the Kathmandu Ring Road was constructed with Chinese assistance.

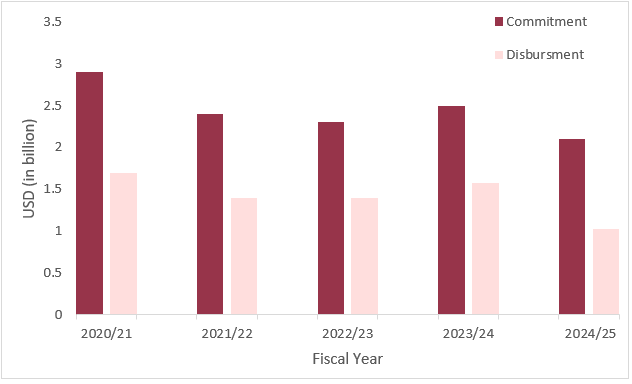

Today, foreign aid remains a central part of Nepal’s development financing. According to the Development Cooperation Report 2024, Nepal received total aid commitments of around USD 2.5 billion in FY 2023/24 AD (2080/81 BS), of which approximately USD 1.58 billion or about 63% worth was disbursed, pointing to persistent challenges in implementation and project absorption, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Foreign Aid Commitments vs. Disbursements, FY 2019/20 – 2023/24 AD (2076/77 – 2080/81 BS)

Source: Ministry of Finance

This persistent gap reflects deeper structural issues within Nepal’s aid management framework. Factors such as bureaucratic delays, lengthy project approval procedures, and limited institutional capacity have hindered the timely utilization of pledged funds. Strengthening project management systems and enhancing inter-agency coordination are crucial to ensure that foreign aid commitments are effectively converted into tangible development results.

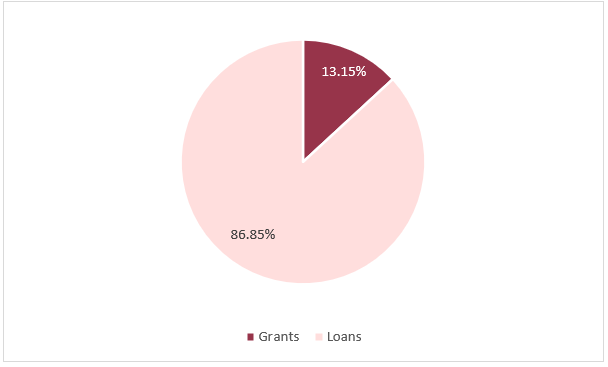

Figure 2. Type of Foreign Assistance in Percent, FY 2023/24 AD (2080/81 BS)

Source: Nepal Rastra Bank

The figure above shows the composition of ODA disbursements to Nepal in FY 2024/25 AD (2081/82 BS). Loans dominated with 86.85% of the total aid reflecting a growing dependence on debt-financed aid. Grants accounted for 13.15%, indicating limited non-repayable support. Data on technical assistance, however, was not available in the NRB records.

This trend heightens the importance of prudent debt management and ensuring borrowed funds generate long-term development returns.

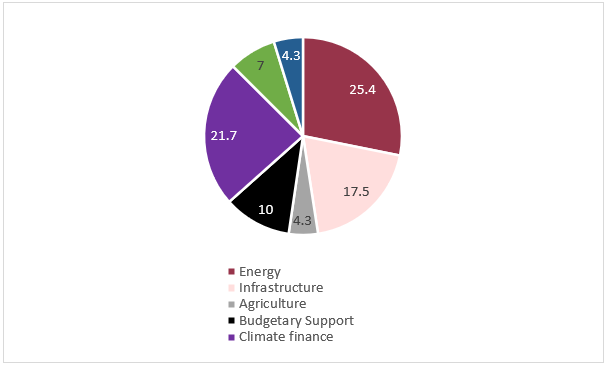

In terms of sectors, education and road transport together accounted for over half of total commitments, reflecting Nepal’s continued dependence on external support for infrastructure and human capital development.

Figure 3. ODA Commitment by sector, FY 2023/24

Source: Development Cooperation Report, Ministry of Finance

Source: Development Cooperation Report, Ministry of Finance

Note: Social is a category used by MoF which includes sectors like education, healthcare, and social welfare and sanitation. In FY 2024/25 AD (2081/82 BS), Nepal’s ODA commitments are concentrated in a few key sectors. Energy leads with 25.4%, focusing on hydropower and electricity infrastructure, followed by Climate Finance at 21.7%, supporting disaster resilience and renewable energy projects. Infrastructure accounts for 17.5%, covering roads, bridges, and urban development. Budgetary Support stands at 10%, providing direct financial assistance for government policies, while the Economic sector receives 7%, targeting banking, SMEs, and trade. Both Agriculture and Social sectors are allocated 4.3% each, with Agriculture supporting irrigation and modern farming and Social programs covering education, healthcare, and welfare initiatives.

Nepal’s government has set a target of receiving approximately USD 2.05 billion in foreign assistance in FY 2024/25, comprising USD 397 million in grants and a significant USD 1.65 billion in loans, indicating a continued reliance on borrowed funds for development priorities.

Understanding FDI: Private Investment from Abroad

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) refers to cross-border investment by foreign companies or individuals who acquire a lasting stake (10% or more) in a local enterprise. Unlike aid, FDI is driven by profit motives and private capital rather than donor priorities.

Nepal began actively encouraging foreign investment during the Sixth Five-Year Plan (1980–1985), with more formal promotion starting after the 1992 Foreign Investment and Technology Transfer Act. These reforms opened most sectors to foreign participation, including energy, manufacturing, and tourism.

To date, Nepal has approved a total of 7,475 foreign investment projects, with committed capital of approximately USD 5.5 billion. Like past trends, majority of the projects remain small-scale, concentrated primarily in services and tourism, reflecting continued investor interest in these sectors.

China has become a major source of FDI commitments, particularly in hydropower, tourism, and manufacturing. In FY 2023/24 AD (2080/81 BS), Chinese investors committed approximately USD 170 million across 275 projects, accounting for over 44% of total FDI commitments.

However, despite the growing number of approved projects, Nepal’s realized FDI inflows remain modest. Net FDI inflows stood at USD 74.8 million in FY 2022/23 AD (2079/80 BS), according to Nepal Rastra Bank — less than 0.2% of GDP. This highlights ongoing challenges related to investment facilitation, regulatory delays, and political uncertainty.

According to the latest Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB) survey report for FY 2023/24 AD (2080/81 BS), Nepal registered net FDI inflows of USD 67 million — a 36.1 % increase from the previous year. However, this level remains very small relative to GDP and underlines persistent gaps between investment commitments and actual realized inflows.

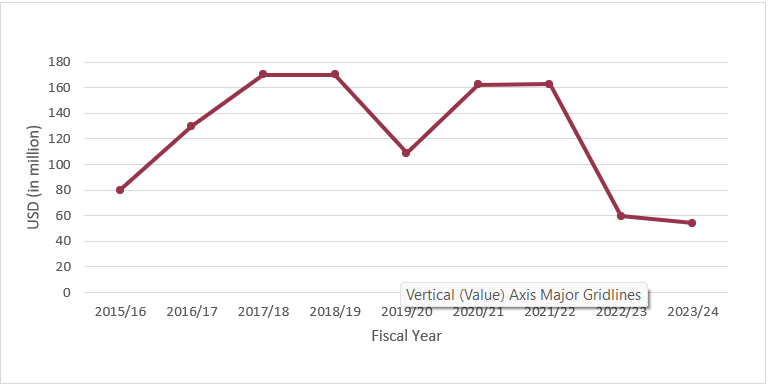

Figure 4. Net FDI Inflows, FY 2015/16 AD (2072/73 BS) – 2024/25 (2081/2082 BS)

Source: Department of Industry, 2025

Source: Department of Industry, 2025

The table shows Nepal’s FDI inflows from FY 2015/16 to FY 2024/25 in USD millions. Inflows fluctuated over the years, starting at USD 149.83 million in FY 2015/16, dropping to USD 103.87 million in FY 2016/17 and further to 100.50 million in FY 2017/18, before rising again to 149.83 million in FY 2018/19. FDI dipped to 108.88 million in FY 2019/20, then recovered to around 150 million in FY 2020/21–2021/22. However, inflows fell sharply in FY 2022/23 to 59.73 million, with a modest recovery to 86.15 million by FY 2024/25, reflecting continued investor caution amid economic and political uncertainties.

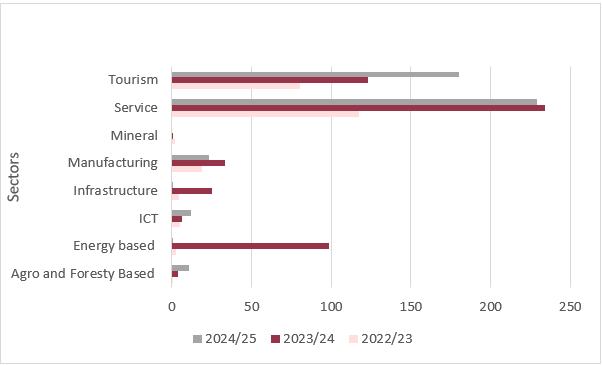

Figure 5. Sector-wise FDI Commitments for Three Years

Source: Department of Industry, 2025

Source: Department of Industry, 2025

The figure shows Nepal’s sector-wise FDI inflows from FY 2021/22 AD (2078/79 BS) to FY 2024/25 (2081/82 BS). The service sector consistently led, peaking at USD 234.3 million in FY 2023/24, touism grew steadily to USD 180.04 million in FY 2024/25. Manufacturing, energy, and infrastructure inflows were volatile, with notable spikes in FY 2023/24 but sharp declines in FY 2024/25. Smaller sectors like agro and forestry and ICT showed gradual growth, whereas mineral received negligible investment. Overall, the data highlights that services and tourism remain the main drivers of FDI, while other sectors experience high fluctuations.

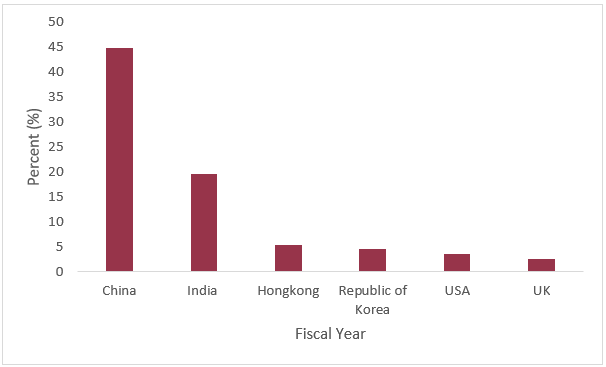

Figure 6. Top FDI Contributor Country Commitment FY 2023/24

Source: Department of Industry, 2025

Source: Department of Industry, 2025

The table shows China accounted for the largest share at 44.77% in FY 2024/2025 AD (2081/82 BS), followed by India with 19.55%. Other contributors included Hong Kong (5.36%), the Republic of Korea (4.61%), the USA (3.47%), and the UK (2.54%). This data indicates that Nepal’s FDI remains heavily concentrated in Asian economies, particularly China and India.

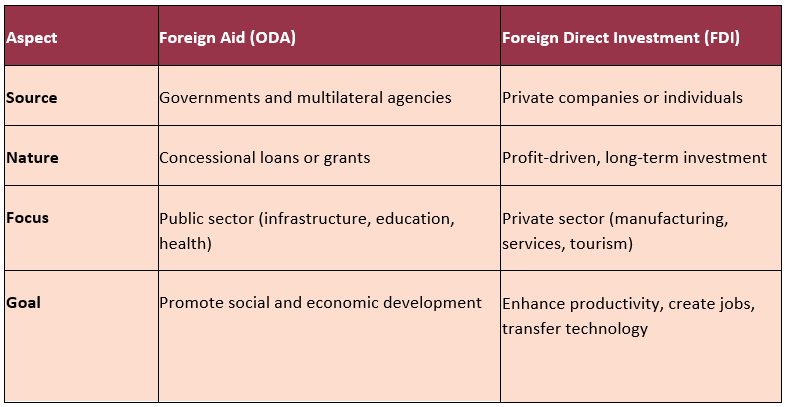

Aid and FDI: Complementary Roles

Although foreign aid and FDI differ in purpose and mechanism, both play critical roles in Nepal’s development.

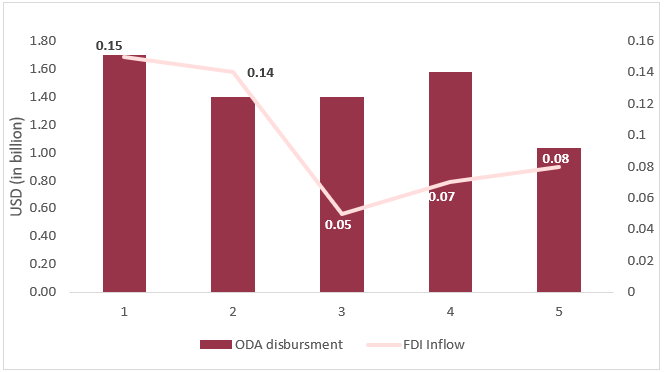

Figure 7. Aid vs. FDI Inflows, FY 2024/2025

Figure 7. Aid vs. FDI Inflows, FY 2024/2025

Source: Department of Industry; Development Cooperation report; Nepal Rastra Bank

Source: Department of Industry; Development Cooperation report; Nepal Rastra Bank

The figure illustrates Nepal’s external financial inflows, comparing ODA disbursements and FDI inflows over FY 2019/20–2024/25. It shows that ODA remains the dominant external source, peaking at USD 1.70 billion in FY 2020/21 before declining to USD 1 billion in FY 2021/22, with a slight recovery to USD 1.58 billion in FY 2023/24. In contrast, FDI inflows are minimal and volatile, falling from around USD 0.15 billion in FY 2020/21 to USD 0.05 billion in FY 2022/24, and slightly increasing to USD 0.08 billion in FY 2024/25.

The graph visually that the country’s external financing heavily relies on public ODA, which is 10 to 20 times larger than private FDI Inflow. This reliance on aid which is increasingly in the form of loans rather than grants indicates a growing future debt burden and a failure to substitute public funds with sustainable private capital investment.

Countries such as Vietnam demonstrate how sequencing aid and FDI can accelerate transformation. In the 1990s, Vietnam used aid to build infrastructure and human capital, then leveraged those improvements to attract manufacturing FDI. The result was sustained economic growth and poverty reduction.

Nepal’s LDC Graduation: A Turning Point

Nepal is set to graduate from the Least Developed Country (LDC) category by November 2026, alongside Bangladesh and Laos. This transition recognizes progress in human development and resilience but also brings new challenges. After graduation, Nepal will gradually lose access to certain LDC-specific benefits including preferential trade treatment and concessional financing. While major donors are unlikely to withdraw support entirely, aid terms may become less favorable. This shift underscores the importance of strengthening domestic resources and improving the investment climate. With concessional aid declining, attracting quality FDI will be essential for sustaining growth and employment.

Looking Ahead: Building Synergy

Foreign aid and FDI should not be viewed as competing sources of finance but as complements. Aid can continue to support foundational needs such as education, governance, and climate resilience while FDI drives private sector growth and productivity.

For Nepal, the priority is to improve the enabling environment: simplify procedures, ensure policy stability, and strengthen infrastructure to make investment viable. Development partners can help by aligning aid programs with private investment facilitation. As Nepal enters its post-LDC phase, balancing aid and investment will be key to ensuring a more self-reliant and resilient economy.

Pushpa Chaulagain holds a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (International Economics and Trade) from Wenzhou University, China. She has experience in economic research, trade policies, and cross-cultural events. Pushpa is passionate about global trade dynamics and aims to contribute to Nepal’s economic development.