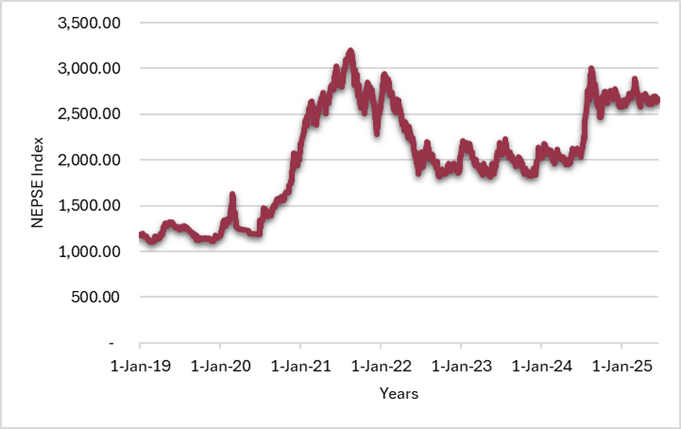

Nepal’s capital market has witnessed a large surge over the past few years, with the Nepal Stock Exchange (NEPSE) index crossing the 2,100 mark as of May 2024. A large reason behind this surge has been the rise of retail investor participation, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic. Retail investors are individuals, particularly non-professional investors, who buy and sell securities using their personal funds. Unlike institutional investors, they typically have limited capital, less access to financial data, and rely on public information or personal judgment to make investment decisions in the stock market. According to data from CDS and Clearing Limited (CDSC), the number of users of Mero Share, the primary financial portal for Nepal, has exceeded 6 million, rising from 742,000 in FY 2019/20 AD (2076/77 BS) to 6.2 million by the end of FY 2024/25 AD (2081/82 BS). However, while the market and retail investor participation are soaring, the question arises about whether these individuals are seeing the full picture. This article explores whether the enthusiasm fueling Nepal’s bull market is grounded in fundamentals or inflated by optimism, and what that means for everyday investors navigating today’s fast-changing financial landscape.

Figure 1. NEPSE Index Trend

Source: NEPSE

Drivers Behind the Rise of Retail Investors

Retail investor participation in Nepal has surged in recent years due to several converging factors. First, the expansion of digital trading platforms has made stock market access significantly easier. Mobile-friendly apps and the digitization of the Trading Management System (TMS) have allowed individuals, including students, homemakers, and part-time workers, to open Demat and trading accounts without visiting brokerage offices. According to data from CDS and Clearing Limited (CDSC), the number of Demat account holders shifted from 1.7 million in July 2020 to 6.9 million by July 2024.

Second, social media and online influencers have played a substantial role. Investment tips and stock recommendations are widely shared on platforms like TikTok, YouTube, and Facebook, often without proper analysis or regulatory oversight. These platforms simplify complex concepts, making trading appear both easy and lucrative, especially to young, first-time investors.

Third, peer influence and community trends have added momentum. According to a 2022 NRB financial literacy survey, over 68% of new investors relied primarily on friends, family, or social media groups for advice, while only a small fraction consulted financial statements or expert analysis.

However, while this democratization of investing has expanded market participation, it also raises concerns, as much of the enthusiasm is built on questionable foundations rather than financial fundamentals.

Risks Lurking Beneath the Bull Market

The rise of retail investors has brought energy and volume to Nepal’s stock market. However, this surge is also driven by a herd mentality, often fueled by online content creators on platforms like TikTok, YouTube, and Facebook. These influencers, who rarely carry professional credentials, share stock tips and investment strategies with little analysis or disclaimers. As a result, many individuals jump into the market based on hype rather than research.

While wider participation in the stock market is a positive development, it comes with risks that are often unrecognized or ignored by new investors. Below are four major risks currently shaping Nepal’s capital market that retail investors may be underestimating:

- Behavioral Biases at Play

Retail investors are not always driven by logic or data. Many fall prey to psychological traps that affect how they make financial decisions. A common bias is overconfidence, where individuals overestimate their knowledge or ability to time the market. Another is recency bias, where people assume that because the market has been going up recently, it will continue to do so indefinitely.

These biases are further amplified by herd behavior, especially in online spaces. When everyone around is buying the same stock, investors’ fear of missing out (FOMO) kicks in and they follow the crowd. The risk here is that many people end up buying at the peak of the market, without considering company fundamentals, and panic-sell when prices fall, thereby leading to losses. Hence, these behaviors reduce rational decision-making and increase market volatility, especially in a retail-driven environment.

- Disconnect Between Stock Prices and Company Fundamentals

One of the most concerning signs in Nepal’s current bull market is the gap between share prices and real business performance. Many companies are being traded at very high valuations without showing matching growth in earnings. For example, some companies listed on NEPSE are trading at price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios above 40, compared to the typical 15-20 range in emerging markets.

A strong example is the commercial banking sector. Even though non-performing loans (NPLs) , which are the loans unlikely to be repaid, have risen to 4.83% (from 3.65% the previous year), bank stocks continue to rise. This suggests that investors may be ignoring financial red flags.

Thus, if stock prices are rising without real business growth, the market becomes fragile and vulnerable to sharp market corrections when reality catches up.

- A Market Outpacing the Real Economy

According to NRB’s report on the Current Macroeconomic and Financial Situation (three months ending mid-October 2024/25),The NEPSE index jumped by over 47% year-on-year, and market capitalization increased by more than NPR 1.5 trillion. While this growth is impressive, the real economy is not growing at the same pace. In other words, the stock market is growing faster than the economy beneath it. This disconnect creates a risky situation. A stock market that rises on optimism and speculation rather than earnings and productivity is like a balloon expanding too fast; it may eventually burst.

Retail investors may be overly confident in a market that’s not supported by economic fundamentals, increasing the risk of sudden downturns.

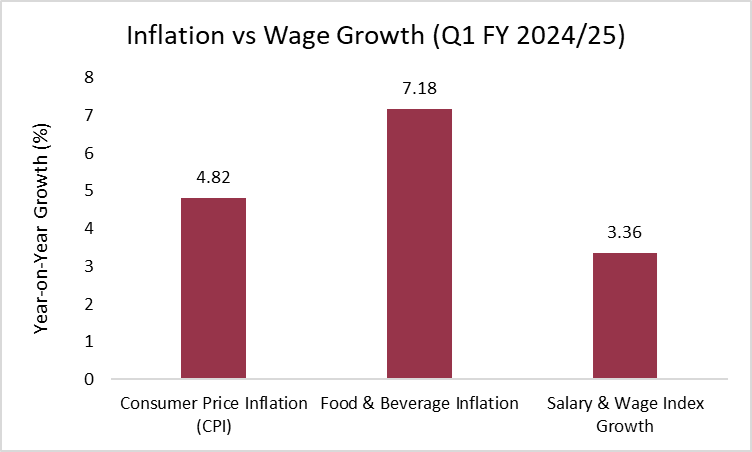

Figure 2. Inflation vs Wage Growth (y-o-y)

Source: Nepal Rastra Bank

- Over-Reliance on Dividend Stocks

Many retail investors in Nepal prefer companies that offer regular dividends, like banks and hydropower firms. Dividends are portions of a company’s profit paid out to shareholders and are often seen as “safe” returns. However, not all dividends are sustainable.

Imagine a company is like a tree. Dividends are the fruit. If the tree is unhealthy but keeps giving fruit, it may not last long. Some firms are giving out dividends even when their cash flows are negative or they are taking on debt. These are known as dividend traps – they look attractive, but they may be signs of deeper financial problems.

Therefore, if a company cuts its dividend in the future or its financials worsen, share prices could fall, leaving dividend-focused investors with both lower income and capital loss.

Way Forward

To ensure sustainable market growth and protect retail investors, coordinated efforts across institutions, regulators, and the media are essential. Institutional support and policy interventions must prioritize investor protection. Regulatory bodies like the Securities Board of Nepal (SEBON) and NEPSE should continue to strengthen market surveillance by improving real-time monitoring of unusual trading patterns, requiring disclosures of insider trades, and enforcing penalties for misinformation. In recent years, SEBON has also taken steps to halt price manipulation, mandate disclosure of material information, and regulate margin trading more strictly.

Promoting financial literacy is equally critical. Targeted education initiatives through schools, universities, and local governments can equip individuals with tools to analyze market fundamentals. Platforms like NRB’s financial awareness campaigns and SEBON’s investor education programs should be expanded to reach broader demographics, particularly in rural and semi-urban areas.

The role of independent research and media is also vital in shifting focus from speculative investing to informed decision-making. Encouraging Nepali platforms to provide accessible, data-backed analysis, similar to India’s Zerodha Varsity which educates millions of investors, could be a strong step forward.

Ensuring long-term success in Nepal’s capital market requires building a well-informed investor base that is resilient to market cycles and misinformation. Learning from international practices, regulators could also promote simplified mutual fund products, encourage robo-advisory tools, and mandate basic investor training for new account holders. These efforts would help foster an investment culture grounded in knowledge, not hype.

Conclusion

The bull market in Nepal’s stock exchange has created unprecedented opportunities for wealth creation, particularly for retail investors. However, unchecked optimism and limited understanding of market dynamics can expose investors to avoidable risks. As the capital market matures, it is crucial that enthusiasm is matched with caution, and that decisions are rooted in fundamental analysis rather than hype.

To safeguard investor interests and sustain capital market development, stakeholders must work together to enhance financial literacy, strengthen regulatory oversight, and promote analytical tools that support informed decision-making. Only then can Nepal’s retail investment boom translate into long-term, inclusive financial growth.

Shivalika Malla is a Research Intern at the Nepal Economic Forum. She is currently doing her Bachelor's in Business Administration with specialization in International Business from Islington College. She is passionate about economics, with keen interests in international relations and business psychology.