Nepal was hit by devastating earthquakes in 2015 which impacted an estimated eight million people, almost one-third of the total population of Nepal. While the earthquake impacted all the sectors in the country, the damages and losses as seen in private housing were enormous. While there have been many ways of evaluating such housing losses, the one that seems apt for the disaster in Nepal is from Mary C. Comerio in her book Disaster Hits Home: New Policy for Urban Housing Recovery.

Comerio proposes an alternate structure for evaluating housing losses. She mentions that counting damaged buildings is not enough to estimate housing reconstruction needs, and to comprehend the full extent of disaster losses, an alternate measure should be incorporated. Each of the proposed measures are evaluated in this article considering the 2015 Gorkha Earthquake.

Measurement of the Amount of Housing Damage Relative to Other Building and Non-Building Damages

The damages seen in private housing have been significantly higher than any other infrastructure or other sector. As per the Post Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA), conducted immediately after the 2015 earthquake, it was estimated that a total of 498,852 private houses had fully collapsed and 256,697 houses were partly damaged. Similarly, 2,656 government buildings were destroyed and 3,622 were partially damaged. In the case of health infrastructure, 6,422 were damaged and 1,122 were partially damaged. Whereas, for schools, 28,064 were damaged and 3,254 were partially damaged. However, the housing sector clearly required most of the reconstruction needs at 49% of the total reconstruction needs; followed by education and tourism which required only 5.9% and 5.8% of the total construction needs respectively.

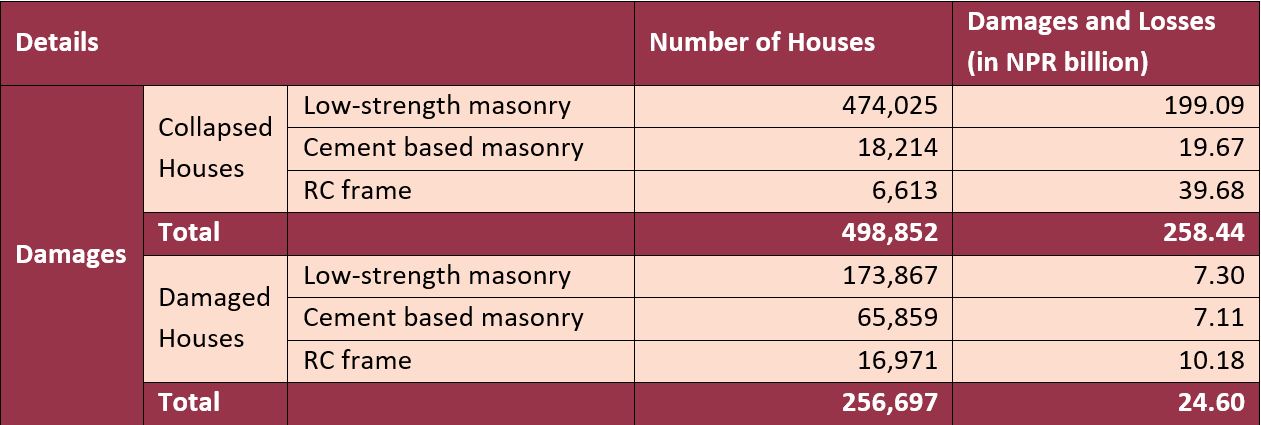

The built environment of Nepal, which consisted majorly of seismically vulnerable structures of unreinforced masonry, was the cause for the catastrophic effects of the earthquake in the country. In 31 earthquake-affected districts, 58% low-strength masonry, 21% cement-based masonry, 15% reinforced concrete frame and 6% bamboo and wood-based structures existed. Further, out of the total collapsed buildings, 95% of the collapsed buildings were low-strength masonry structures, 3.7% were cement-based masonry structures and 1.7% were reinforced concrete frame structures collapsed. The same is reflected in Table 1.

Table 1. Losses seen in different building types

Source: National Planning Commission, 2015

The mud-bonded bricks/stone houses or low-strength masonry houses lack integrity between different structural members and include materials that have inherently weak properties. Due to these problems, such buildings perform poorly during seismic events and usually result in parapet and gable wall toppling, out-of-plane toppling of walls, and various types of wall failures during earthquakes.

Differentiation of Damage to Single and Multi-Family Dwellings

The 2015 Gorkha Earthquake impacted the different parts of Nepal, i.e rural and urban, differently, especially when it comes to the housing and human settlement sector.

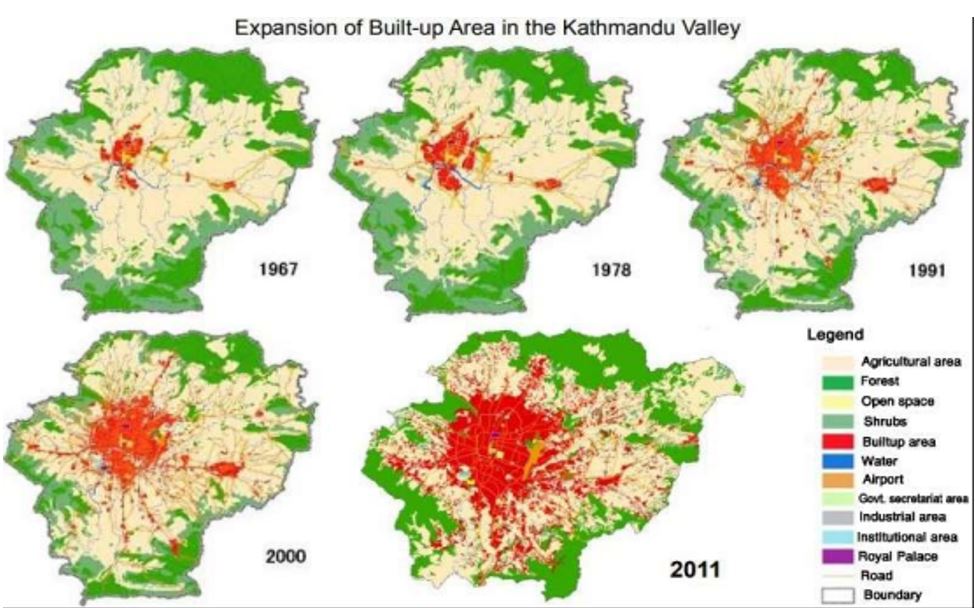

Urban areas in Nepal, particularly the Kathmandu Valley, have experienced rapid and haphazard settlement growth due to urbanization, poverty, high land and construction costs, and reliance on owner-built housing. Political instability, including a decade-long civil war, has driven rural-to-urban migration, while centralized policies have concentrated development in urban centers. As a result, Kathmandu Valley, with an estimated 2.54 million people, is growing at 6.5% annually, accounting for 30.9% of Nepal’s urban population.

Figure 1. Expansion of built-up area in Kathmandu

Source: Timsina et al, 2020

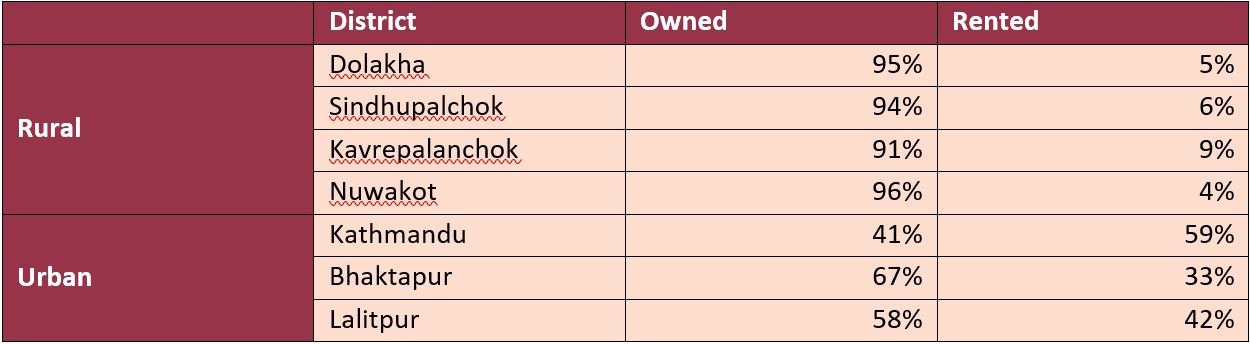

With high housing demand in urban areas, more people live in limited spaces. The 2011 even shows higher home ownership in rural areas, while rentals dominate urban regions. Table 2 presents ownership versus rental percentages for select districts affected by the 2015 earthquake.

Table 2. Comparative table showing owned versus rented spaces in rural and urban areas of Nepal

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) 2012

Considering these factors, during the Gorkha Earthquake, rural renters were minimally affected as most rural residents owned their homes. In contrast, urban renters faced significant challenges due to high demand and limited housing supply, which became even scarcer as multiple structures sustained damage. A robust reconstruction program should consider the types and uses of damaged homes, along with the diverse family structures across the country. A one-size-fits-all housing policy is inadequate, as varying definitions of ‘family’ must be acknowledged in the rebuilding process.

Segregation of Housing Damage by Degree of Habitability

The earthquake was estimated to leave 2.8 million people with damaged or destroyed houses. Out of 2.8 million people, 500,000 were living in their original houses and the remaining 2.33 million population were observed to be living in three types of sheltering situations. 1.58 million people were estimated to be located in “scattered sites”, consisting of less than five households on the land of their damaged house or nearby in open spaces; 117,700 in “spontaneous sites”, consisting of five to fifty households on public or privately owned land without official support; and 636,000 in “hosted sites” with 50 or more households with official support in designated public spaces.

The assessment team deployed by the government inspected houses and categorized them in three different colors: red, yellow and green. A house denoted as red meant it was unsafe to live in and would be brought down if it had not already. Yellow indicated that it needed repairs before moving in and houses labelled green were safe to live in.

Based on this segregation, reconstruction efforts prioritized fully destroyed homes through the phased disbursement of funds. However, policies addressing partially damaged houses were delayed. As a result, many homeowners demolished their repairable houses to qualify for government funding allocated for full reconstruction. To prevent such unintended consequences in future disasters, it is strongly recommended that compensation plans be designed to account for varying degrees of habitability.

Estimation of Economic Value of the Losses and the Cost to Rebuild

The 2015 Gorkha Earthquake severely impacted housing and human settlements, accounting for USD 3.27 billion — nearly half of total reconstruction needs. To combat the damage, the government implemented a blanket policy, providing NPR 300,000 for fully damaged homes and NPR 100,000 for retrofittable ones, with reconstruction mandated to meet approved standards.

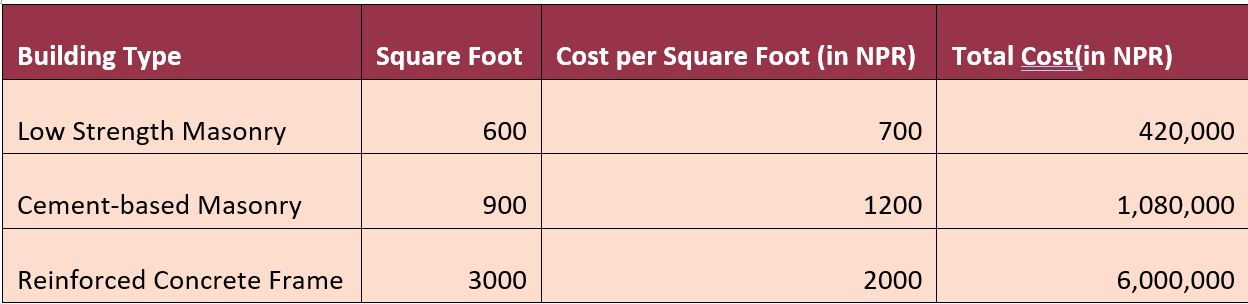

According to the Nepal Living Standards Survey (2010-2011), average house sizes were 600 sq. ft. for low-strength masonry, 900 sq. ft. for cement-mortared, and 3,000 sq. ft. for reinforced concrete structures. Meanwhile, costs per square foot were NPR 700, NPR 1,200, and NPR 2,000, respectively, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Cost as per building type

Source: National Planning Commission, 2015

Although the cost per square foot is based on 2011 rates, it was expected to rise by at least 10% by 2015, making actual construction costs higher. While 95% of damaged homes were low-strength masonry, government funding covered only 70% of the 2011 cost, dropping to around 65% when adjusting for inflation. For cement-based masonry and reinforced concrete houses, government support covered just 28% and 5% of costs, respectively. Therefore, the total economic losses likely exceeded official estimates, as reconstruction costs were higher than initially calculated.

Description of the Concentration of Residential Losses

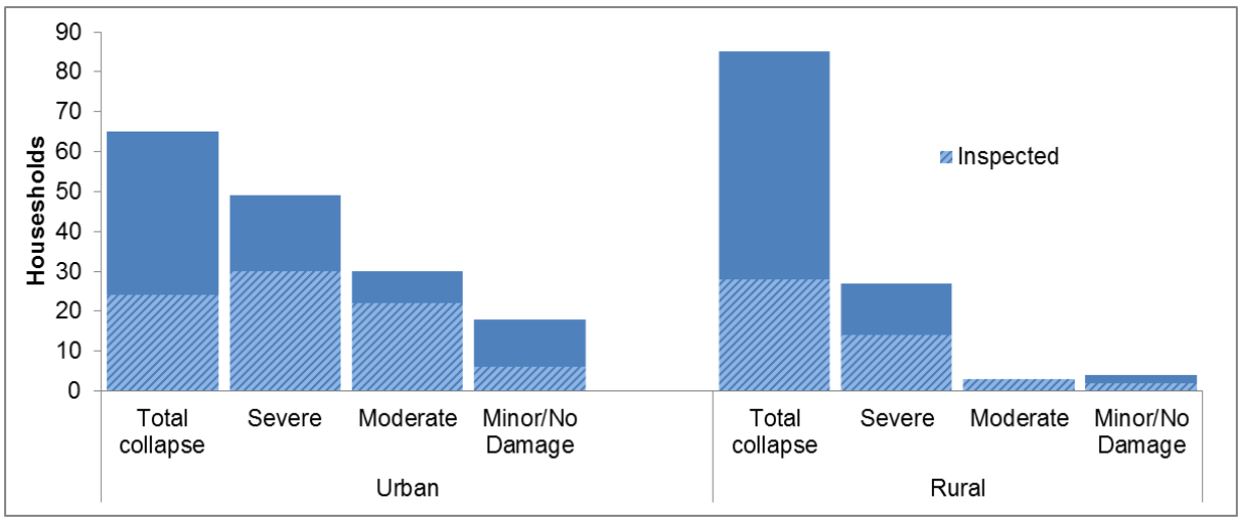

The 2015 Gorkha Earthquake is regarded as a rural disaster since it majorly affected the rural districts and communities. As per Figure 2, majority of private houses in both urban and rural areas experienced total collapse. However, the number of collapsed houses in rural areas was much higher than that of severely and moderately damaged houses. Meanwhile, urban areas had significant number of severely and moderately damaged houses, mainly due to the type of houses built in urban places.

Another reason for houses to sustain limited damages in urban areas is the use of better materials and workmanship. As people residing in urban areas usually have better income than rural areas, households in urban areas spend more money in construction of their houses. Further, better materials are used in the buildings and so is better workmanship. Also, people residing in urban areas tend to use professional services of experts such as engineers and architects while people in rural areas build non-engineered buildings themselves.

Figure 2. Level of damages of private houses in rural and urban parts of Nepal

Evaluation of Housing Damage Relative to Local Conditions

In order to develop an integrated plan for reconstruction and rehabilitation after a big disaster, it is important to understand the socio-economic condition of people and how the disaster has impacted their everyday lives.

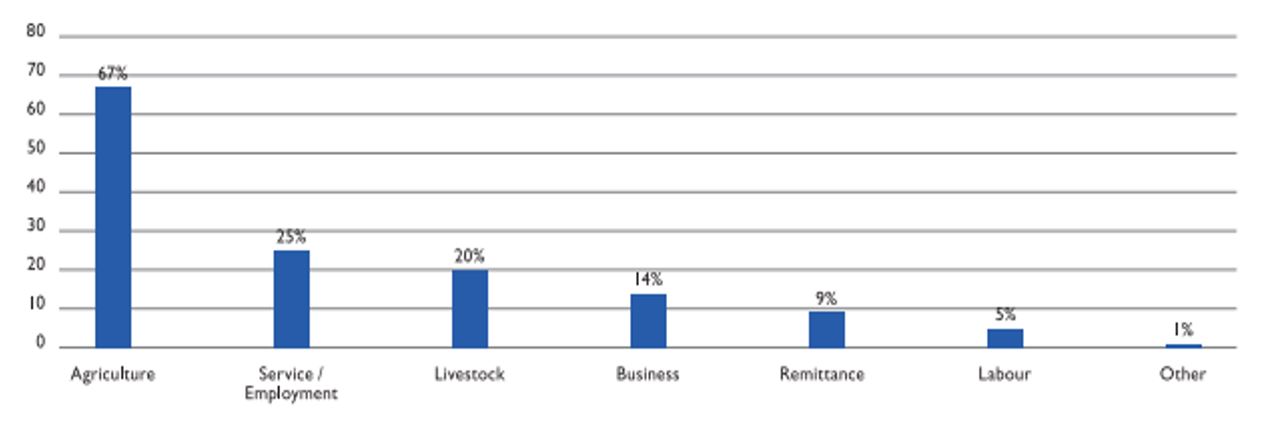

Figure 3. Sources of income for 14 districts

Most people in earthquake-affected districts rely on agriculture as their primary source of income, followed by service and tourism-related employment, as shown in Figure 3. Considering this, the earthquake greatly affected the livelihood of those in earthquake-affected districts as the PDNA report estimated that nearly 1,000 hectares of land were rendered unusable due to landslides, resulting in losses of approximately NPR 28.37 billion in the agriculture sector.

The prime example of this was in Sindhupalchok, where about 78% of the economically active population depends on agriculture, forestry, and fisheries. Farmers in this district primarily grow wheat, rice, maize, and potatoes. Many of these farmers lost their harvested crops and stored seeds due to the collapse of homes and storage structures. Similarly, in Rasuwa, where 63% of the land lies above 3,000 meters, tourism, especially in Langtang Valley, is a key economic driver but this was greatly affected as earthquake-induced avalanches and landslides blocked trails, severely limiting income opportunities.

Beyond agriculture and tourism, many residents in these areas migrate to urban areas or abroad for better work prospects. Even for them, the Employment and Livelihoods assessment estimated that the earthquake disrupted livelihoods for millions, resulting in the loss of 94 million workdays and NPR 17 billion in personal income for that year.

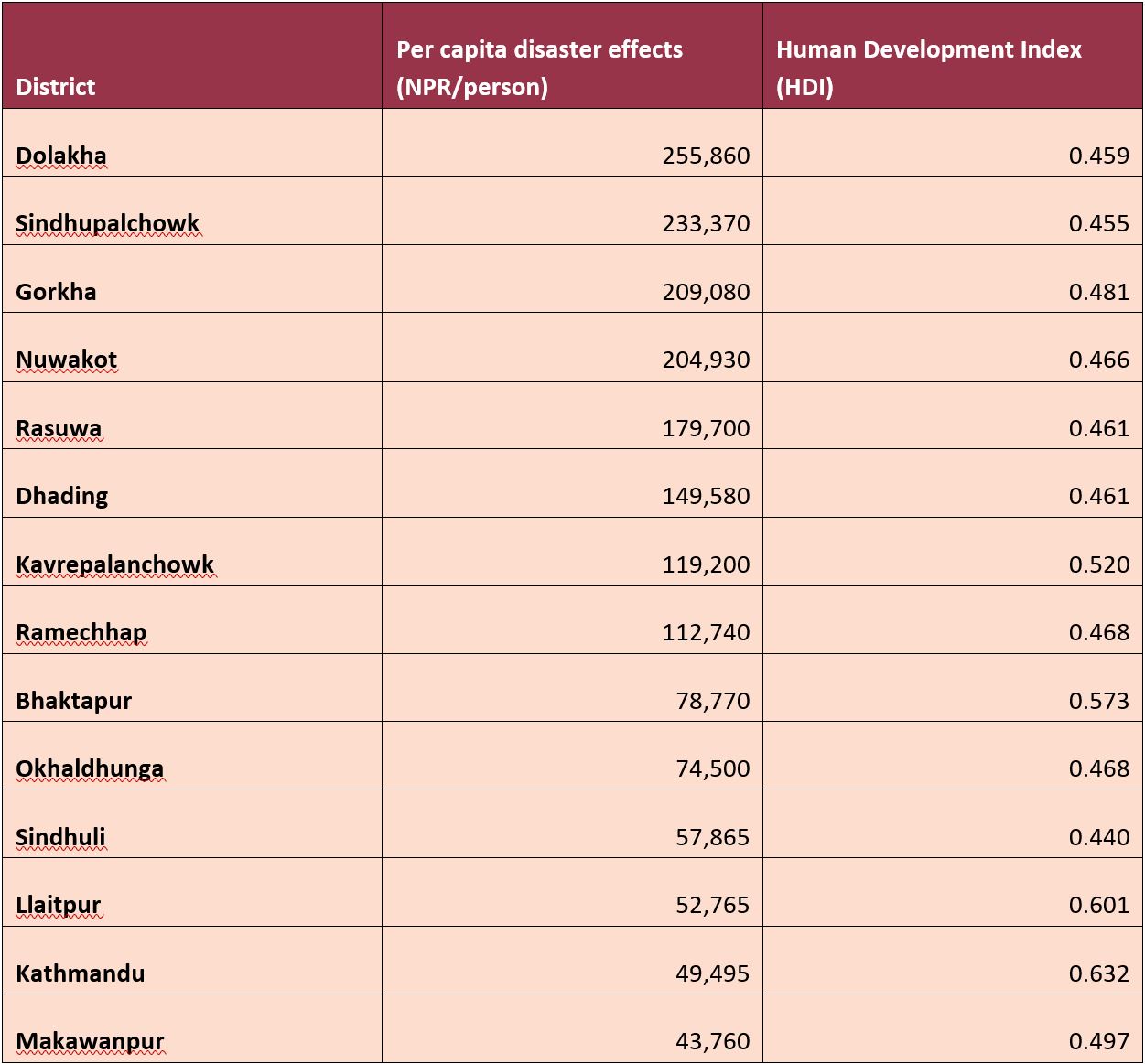

Disasters disproportionately impact the poorest and most vulnerable, and the 2015 Gorkha earthquake was no exception. The per-person disaster impact ranged from NPR 255,860 in Dolakha to NPR 43,800 in Makawanpur, averaging NPR 130,000 across the 14 hardest-hit districts, as shown in Table 4. Notably, the six lowest-HDI districts — Dolakha, Sindhupalchowk, Gorkha, Nuwakot, Rasuwa, and Dhading — experienced disaster effects exceeding NPR 130,000 per person.

Table 4. Per capita disaster effects and pre-earthquake HDI in earthquake-affected districts

Source: National Planning Commission, 2015

Conclusion

Mary C. Comerio’s framework provides a valuable framework for evaluating post-earthquake housing recovery, particularly in the context of Nepal’s 2015 Gorkha Earthquake. Comerio emphasizes the need for well-structured housing recovery policies that address immediate shelter needs, long-term reconstruction, and economic resilience. Applying her insights to Nepal, the government’s blanket policy failed to consider variations in housing types, income disparities, and regional differences, leading to challenges in equitable recovery. Nepal’s reliance on direct cash transfers without a flexible approach hindered efficient reconstruction, particularly for urban renters and low-income households.

The Gorkha earthquake demonstrated the importance of a more adaptive and inclusive housing policy — one that considers social, economic, and geographic factors. Thus, Comerio’s work underscores the need for Nepal to develop disaster recovery plans that go beyond uniform assistance, ensuring sustainable rebuilding and greater resilience for future disasters.

Jini Agrawal is the Country Manager at Miyamoto International Nepal, a global engineering and risk reduction firm. With over a decade of experience, she has worked closely with government departments, private businesses, UN agencies, international banks, and other partners to promote resilience and advocate for a sustainable built environment in Nepal. In addition to her national leadership role, she also works across regional and global teams to drive the company's international development and humanitarian assistance strategy and partnerships. She has led the development and implementation of numerous resilience and recovery projects across the Asia-Pacific region.