Thangka is a Buddhist-style painting on cotton or silk, depicting a Buddhist deity, scene, or mandala. It serves both as a form of meditation and a symbol of spirituality with its artistic and aesthetic value having grown over the years, driven by touristic and religious trade. This type of painting was introduced in Nepal as early as the 7th century, and further evolved under Chinese artistic influence from the 14th century. While the more popularized name of this painting is thangka, the purported original version of this is the Newari style called paubha.

Although thangka and paubha are often considered to be the same, including in official records such as those kept by the Federation of Handicraft Associations of Nepal (FHAN), there remains a distinction between the two, albeit often disputed. Thangka is commonly associated with Tibetan Buddhism, while paubha is a term used in Nepal to describe similar works of art in the Newar Buddhist tradition. While both types of paintings serve religious purposes and feature similar iconography, such as deities, mandalas, and spiritual themes, the key difference lies in their stylistic elements and regional variations. According to some artists, thangka paintings often have a more rigid, systematic approach with specific guidelines for composition and iconography, especially in Tibetan traditions.

In contrast, paubha paintings have unique Nepali influences, incorporating local elements, styles, and techniques that differentiate them from their Tibetan counterparts. Additionally, according to some other artists and Newari legends, the paubha that originated in the Kathmandu valley was taken by Princess Bhrikuti to Tibet when she married the Tibetan king Sron Tsan Gampo in the 8th century, and it is this paubha that evolved into the popular thangka. Regardless of these disputed origins and differences, both thangka and paubha art forms share a common purpose of promoting spiritual enlightenment.[1]

In terms of creating a thangka painting, it is a detailed process that blends art with spirituality. The artist begins by preparing a cotton or silk canvas, coating it for smoothness. They then sketch the design, apply natural pigments in layers, and use fine brushwork to add intricate details, often highlighted with gold. Once complete, the thangka may undergo a blessing ritual, transforming it into a sacred object of devotion.

Thangka as an Economic Driver

At a time when people worldwide are seeking deeper connections to mindfulness, spirituality, and culture, thangka paintings, with their rich history and intricate designs, hold significant economic value in both domestic and international markets.

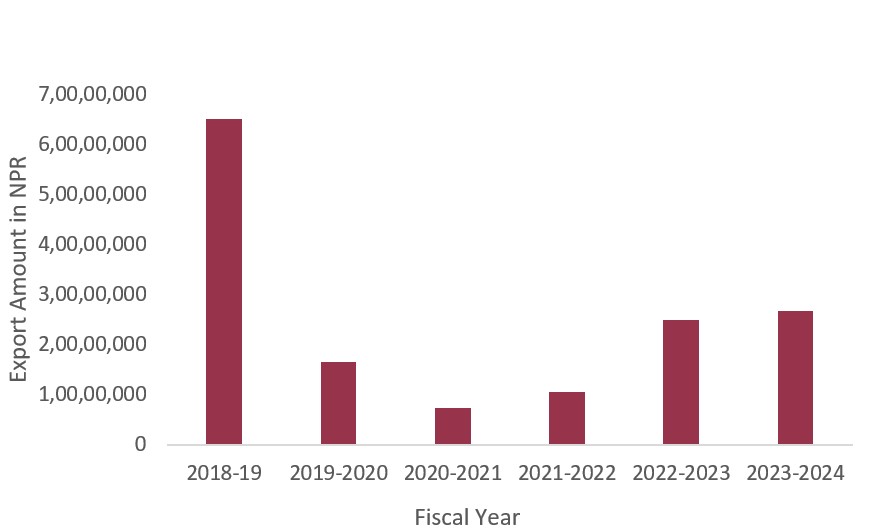

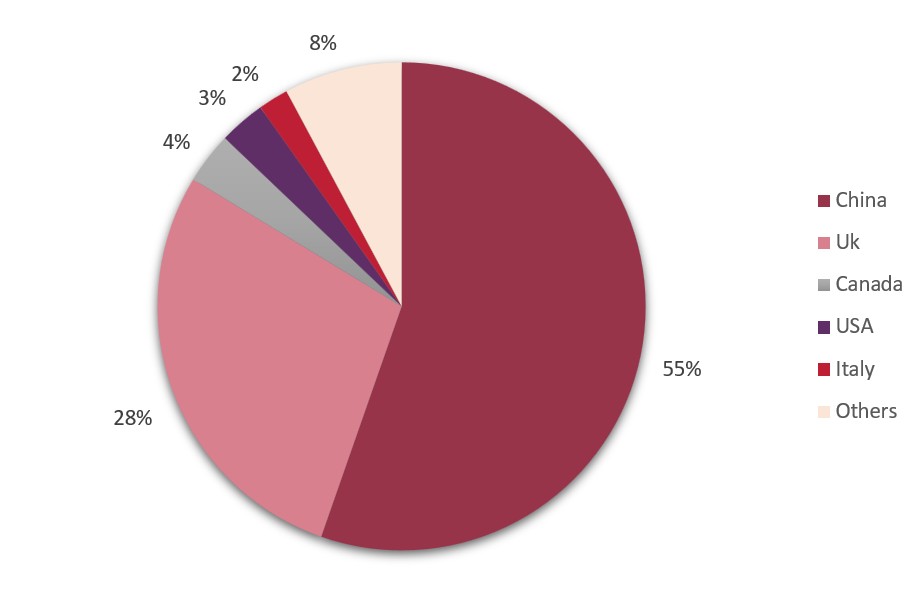

According to information provided by the Federation of Handicraft Associations of Nepal (FHAN), Nepal exported handicrafts worth more than NPR 3 billion by May 28 of FY 2023/24 AD (2080/81 BS). Thangkas make up a large part of these exports. While export figures have fluctuated from 2018 to 2024 AD, largely due to external factors like the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall trend shows a promising recovery and growing demand, as shown in Figure 1. Within thangka exports, China dominates the market, accounting for 55.4% of the total export revenue, as shown in Figure 2.

On a more micro level, depending on the level of expertise, difficulty, and time required, thangka painters could earn anywhere from USD 20 (NPR 3,000) to USD 15,000 (NPR 2.08 million) in 2023 itself. Thus, as global interest in mindfulness and cultural heritage grows, thangka’s economic potential remains poised for further expansion.

Figure 1. Multiyear Data of Thangka/Paubha Export

Source: Federation of Handicraft Associations of Nepal

Figure 2. Thangka Export Distribution by Country (FY 2023/24 AD (2080/81 BS))

Source: Federation of Handicraft Associations of Nepal

Challenges

Despite rich heritage, cultural significance, and global appeal, Nepal’s thangka art sector faces numerous challenges which prevent it from reaching its full potential. The artisans, the backbone and soul of this sector, are particularly affected, struggling with a range of issues.

Declining Interest in Learning Thangka Art

Among younger generations. thangka painting, traditionally passed down through families and schools, is increasingly seen as a labor-intensive and less financially-viable career choice compared to other professions. Many young people are now choosing to pursue more modern, technology-driven careers, which has resulted in fewer apprenticeships and a decline in the number of skilled thangka artists. This generational gap in expertise threatens the future of the art style and its ability to sustain itself as a viable cultural tradition.

Lack of Awareness

Thangka and paubha share similar themes but come from distinct backgrounds. However, both are often marketed as the same, leading to thangka being seen as purely Tibetan. This misconception limits the recognition of paubha as a unique Nepali art form, making it harder for both to establish their own identity in the global market.

Market Dependency on Tourism

The thangka art market in Kathmandu heavily relies on tourism. Tour guides often dictate which shops receive business, and artists receive minimal compensation for their work. For instance, according to some accounts, artists spend months creating thangkas but are paid only a fraction of what they are due, with tour guides taking up to 50% commission.

Competition from Mass-Produced Goods

The rise of mass-produced goods poses a significant threat to Nepal’s thangka market. Cheaper, machine-made prints and mass-produced replicas of thangkas often flood the market, offering lower prices that many consumers find hard to resist. This competition makes it challenging for handmade goods, which require time, skill, and effort, to compete on price.

Future Prospects

The future of Nepal’s thangka industry holds great potential if strategic efforts expand its reach and strengthen its foundation. Increasing international exposure through exhibitions in key markets and emerging markets can increase global recognition and demand. Further, the government can support growth by designating more thangka hubs to centralize resources, training, and markets while offering financial incentives to lower production costs and encourage high-quality artwork.

Moreover, investing in professional training for both novice and experienced artists can help preserve traditional thangka techniques while encouraging innovation. Additionally, thangkas and paubhas face a face major problem with a lack of proper marketing. Thus, marketing strategies should be made that focus on sharing the cultural and spiritual stories behind each piece to elevate its value, and challenge the misconception of thangka as solely a “Tibetan” art. A strong, cooperative community is equally vital as, by pooling resources, adopting unified marketing strategies, and partnering with international galleries, Nepali thangka artists can access broader opportunities. With collective efforts from artists, policymakers, and stakeholders, the thangka industry can thrive, preserving Nepal’s heritage while expanding its global presence.

[1] For ease of reading, the author refers to all the paintings collectively as thangkas hereon, though this may include paubhas as well.

Pushpa Chaulagain holds a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (International Economics and Trade) from Wenzhou University, China. She has experience in economic research, trade policies, and cross-cultural events. Pushpa is passionate about global trade dynamics and aims to contribute to Nepal’s economic development.