Women, Business, and the Law 2022 assessed 190 economies across eight indicators: mobility, workplace, pay, marriage, parenthood, entrepreneurship, assets, and pensions.

Background

Women, Business, and the Law (WBL) is a World Bank Group project that collects unique data on the laws and regulations that limit women’s economic opportunities and possibilities. It presents its findings in the form of an index covering 190 economies. The index assesses explicit discrimination in the law, legal rights, and the provision of certain benefits, all of which are areas where improvements can help improve women’s labor force participation. Considering this, the index is measured across eight indicators that include mobility, workplace, pay, marriage, parenthood, entrepreneurship, assets, and pensions revolving around the life cycle of a working woman (Figure 1.).

Figure 1 Eight indicators of Women, Business, and the Law Report

Source: Women, Business, and the Law Report (extracted from the report, p.2.)

The dataset aims to provide and serve as a basis for objective and quantitative standards for worldwide gender equality progress. It also aims to develop comparable data across economies, which can have a broader scope for research, policy discussions, and so on, targeted towards enhancing women’s economic opportunities. For this, 35 questions are scored across the eight indicators mentioned above. The average of each indicator is then measured, where 100 represents the highest score.

In line with this, the WBL 2022 report is the eighth report in a series of annual studies. The first report was published in 2008. It has measured 190 economies across eight indicators: mobility, workplace, pay, marriage, parenthood, entrepreneurship, assets, and pensions.

What’s new in this report?

Besides the eight areas, this year’s WBL 2022 report has conducted pilot research on legal frameworks for accessible, affordable, and high-quality childcare and how laws are implemented. It has, thus, included the preliminary findings of the same.

Highlights from the Women, Business, and the Law report 2022

- The global average score for Women, Business and the Law is 76.5 out of 100, suggesting that approximately 2.4 billion working-age women are still deprived of equal legal rights as men.

- High-income regions such as Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean scored the highest average scores. In contrast, the Middle East and North Africa were in the lower range (53 average scores). However, expert opinions indicated that gender equality was more in practice than the index implied in the Middle East and North Africa, whereas the index seemed to have exceeded expert views in all other regions (particularly in the Workplace indicator).

- Out of a man’s predicted total lifetime income, women only earn two-thirds, indicating the possibility of widening the gap between the economic disparities. However, if this gap can be addressed, the positive spillover effect will be seen globally.

- The greatest inequalities observed in the report is in the area of Pay and Parenthood, indicating that many economies have failed to eliminate limitations or implement the recommended legal rights and benefits. However, the report also noted that the Parenthood indicator recorded the highest number of reforms over the past year, followed by Workplace and Pay. This indicates that economies are identifying and seeking to address the inequalities, but the pace can be improved.

- Evidence shows that a more equitable legal framework is linked to a higher proportion of female entrepreneurs. Furthermore, women’s advancements are related to business productivity as well; hence, if discriminatory practices are controlled and eradicated, then sales, labor and overall business productivity can also be improved.

- Child care is one of the vital elements of women’s economic participation. Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for childcare policies has only been heightened, especially for working parents and, more so, working mothers. Considering this, the report examined the legal framework of three pillars of childcare (affordability, availability, and quality) through piloting in 95 economies.

- When there is a provision for all three pillars in an economy, it can result in better labor market outcomes for women, improved child development outcomes and increased economic growth for the economy as a whole. Such provisions are regulated by the state in most OECD recognized high-income countries and by the private sector or employers in the Middle East, North America, and South Asia.

- Even in their entirety, laws are not enough to improve the scores across all indicators. The gaps that exist require tremendous and continued focus on enforcement and monitoring.

Results for Nepal

Nepal was also among the 190 economies that was covered by WBL 2022 report, but the data and the laws that the report has considered are only applicable to the capital city of Kathmandu.

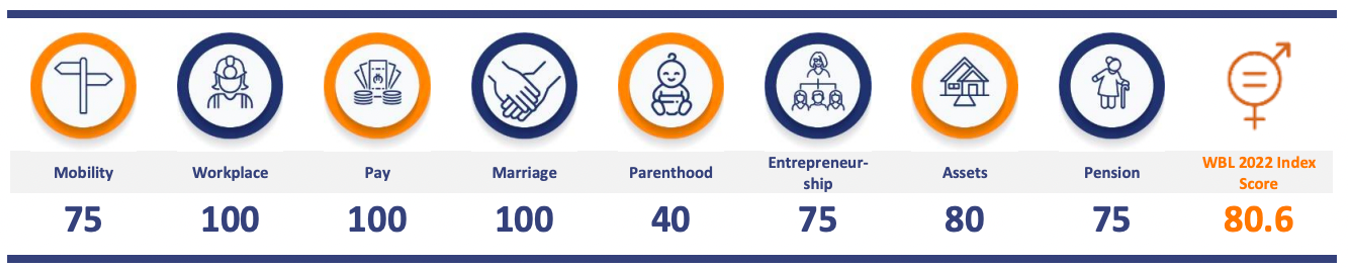

Nepal scored 80.6 out of 100, which is higher than the average across countries of South Asia (63.7). In comparison to Nepal, India scored 74.4 points, followed by Maldives (73.8), Bhutan (71.9), Sri Lanka (65.6), Pakistan (55.6), Bangladesh (49.4) and Afghanistan (38.1).

Figure 2 Nepal’s scores in the eight indicators of the WBL 2022 report

Source: Women, Business, and the Law Report (extracted from the report, pg. 114.)

The report showed that Nepal scored 100 on women’s decision to work (Workplace), laws affecting their pay (Pay) and constraints related to marriage (Marriage). Likewise, the lowest score achieved was on the Parenthood indicator, i.e., the laws pertaining to women’s work after having children.

Possible considerations for Nepal for improvement of the score

- Exploring public provision for the effectiveness of Parenthood indicator which means that the government may change the existing laws to requirement and administration of 100% of maternity leave benefits, availability of paid parental leaves, and prohibition of the dismissal of pregnant workers. Economies like Armenia, Switzerland, Colombia, Georgia, Greece, Spain, and Ukraine addressed their inequalities since the release of the WBL 2021 report and introduced paid paternity leaves, while Hong Kong and China increased the paid maternity leave duration to a minimum of 14 weeks. In Nepal, the Labor Act 2017 does not recognize paternity leaves. It only provides the provision of a male labor whose wife is going to deliver, a paid maternity care leave for 15 days’ per the Article 45.

- Revisiting and amending the National Civil Code Act 2017 as it poses restrictions on the mobility of women. One of the questions that the report measures in the Mobility indicator are ‘Can a woman choose where to live in the same way as a man? ’ To which the answer in the case of Nepal is ‘No’. In line with this, the National Civil Code Act 2017 (Article no. 87) states that ‘Husband’s home to be considered a residence except where a separate residence is fixed by a mutual understanding of the husband and wife, the husband’s home shall be considered to be the wife’s residence.’ In a country where at least 26% of every married woman had experienced domestic, physical, sexual or emotional violence throughout their lifetimes, such an article can push the women to more miserable and vulnerable living conditions that also limits their economic productivity potential. Hence, there is a need to revisit and amend such acts.

- Revisiting and amending the Passport Regulation 2020 and Citizenship Act 2006 as they also limit women’s freedom to move or even independently pass the citizenship to their children. There are gender discriminatory laws, practices and administrative burdens in place in the case of a woman that has their roots in patriarchal and conservative mindsets. Such discriminatory treatments are also often conducted by the officials who are responsible for the administrative purposes of acquiring both citizenship and a passport.

- Strictly implementing enforcement and monitoring principles because although women-run businesses and women-owned properties have increased, most of them do not have control over their assets and businesses.

- Facilitate and create entrepreneurial and safe work opportunities in local communities, with a particular focus on youth and women migrant returnees, who have a greater desire to remain in the country and contribute to national production and employment

This recommendation to create employment opportunities is consistent with one of the major recommendations of the WBL 2022 report. It argues that women’s economic rights should be strengthened to ensure equal access to government assistance programs and digital technology, such as mobile phones, computers and the Internet. If this is done, the WBL team believes it will help them create new enterprises, identify new markets and get better jobs. For this, the government can likewise explore the key changes that are required to boost investment and public-private partnership (PPP), especially in the local economies of Nepal, so that more such self-employment or employment opportunities can be created/facilitated.

Nasala Maharjan is a Bachelor's in Business Administration (BBA Honors) graduate from Kathmandu University with a major in Finance. She is mostly interested in researching and writing about economic development and contemporary issues in Nepal. She joined Nepal Economic Forum (NEF) as a Research Fellow in 2019 and is currently a beed at beed management.