In the world of luxury, Champagne is not just a kind of sparkling wine and Kashmir Pashmina is not just any garment. These are products crafted with an extraordinary history, with stories anchored to their place of origin, and, most importantly, are economic assets that are protected by law. Both of these products command a premium over their generic counterparts. Now, picture the Palpa Dhaka or Ilam tea of Nepal which possess an equally compelling and intricate heritage and story, yet they remain economically vulnerable with their value being diluted in today’s globalized market. This stark difference is the result of a Geographical Indication (GI) tag, a powerful intellectual property tool that Nepal has yet to leverage. As global markets increasingly pay for authenticity, Nepal’s failure to utilize GI tags is not just a hypothetical risk, it is an ongoing drain on national revenue and a missed strategic opportunity.

What is Geographical Indication (GI)?

A Geographical Indication (GI), as per the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), is a sign used on products having a specific geographical origin, unique qualities, or a reputation that is tied to their origin. The modern concept of GI was crystallized formally in the 1994 Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). Some well-known examples of products with GIs are Kampot pepper from Cambodia, Scotch whisky from the United Kingdom, and Café de Colombia from Colombia. Unlike trademarks, which inform consumers about the identity of a commodity originating from a particular company, GIs identify them as being sourced from a particular place. GIs can be protected through different legal means such as the suis generis (Latin for ‘of its own kind’) systems, collective marks and certification marks, trademark laws, and international agreements. This legal tool comes with multiple benefits. GIs help create a development of trust in the marketplace for the consumers as well as serve as a great means of branding for the producers, enhancing the reputation of the region and sustaining local culture. Consumers get assurance about the quality, traceability, and authenticity of the products they purchase while the producers, farmers, artisans, as well as business owners benefit as well.

Nepal’s Legal Framework for GI

Nepal’s legal journey toward GI protection has been slow and remains incomplete despite the fact that Nepal became a member of the World Intellectual Property Organization in 1997. Early frameworks like the Copyright Act, 2002 and the Trademark Act, 2007 offered only indirect, weak protection. The Patent, Design and Trademark Act, 2022 covers certain aspects of GI protection but despite this 2022 Act, a functional GI system is not operational in Nepal. Nepal has drafted an Industrial Property Bill, 2025 that incorporates the provision for registering geographical indications but this has not been implemented yet. There are no GI-tagged products from Nepal as of today. This is in complete contrast to our regional neighbors like India which has had a robust suis generis GI Act since 1999 and, in 2024, had nationally GI-registered more than 658 products from various regions of the state. In the same manner, Bangladesh enacted its GI Act in 2013 and Bhutan has registered several GIs as well.

Cost of Inaction for Nepal

Every day without a GI system, Nepal bleeds potential revenue. The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) states that GI products typically sell at a much greater premium in the market. For Nepali products like tea from Ilam, this means losing millions annually as companies sell an unbranded commodity, while Darjeeling tea thrives. Similarly, iconic crafts like Palpali Dhaka are vulnerable to mass-produced imitations that disadvantage authentic weavers. Without legal support, Nepal cannot stop foreign companies from copying its designs, as nearly happened with India’s Kolhapuri sandals and Prada. This inaction negatively affects rural entrepreneurship, perpetuates the export of raw materials over finished goods, and surrenders control of Nepal’s cultural heritage to the global market.

Lessons from GI Success Cases

Given the situation of geotagging in Nepal, the country can take inspiration from other nations, especially from Asia, as the world offers remarkable instances for turning geographical heritage into economic wealth through the use of GI. The first case is that of India’s Darjeeling tea. Prior to obtaining its GI tag in 2004, fake Darjeeling tea was widespread in the market, tarnishing the brand and reputation of the actual tea. Once the registration was done under India’s suis generis GI Act and the Tea Board of India mandated certification and traceability systems, Darjeeling Tea transformed into a premium brand. It now commands a premium price securing the livelihoods of local workers. Learning from the GI-tagging of Darjeeling tea, Nepal can leverage GI as a legal tool to stop brand theft and protect its own Ilam tea from mislabeling.

Another example comes from the pepper fields of Cambodia which were destroyed by the Khmer Rouge regime. By the 2000s, farmers from the region grew low value pepper as the tradition was almost lost. Then, in 2010, Kampot Pepper received a GI tag with the aim of restoring the quality of the pepper and its production. The Kampot Pepper Association (KPPA) enforced strict regulations and, as a result, the good sells at a much higher price than ordinary pepper, revitalizing the rural livelihoods of the area. For Nepal, this instance shows that a GI tag can strategically promote authentic, traditional agro-products, thereby providing a great model for our unique Mustang sea buckthorn or even Jumla Marsi red rice.

Persisting Challenges

The GI model is not without critique and complexity despite being powerful. First, it can be bureaucratic and exclusionary. Setting up a legal GI system is costly, and defining the precise geographical area and traditional methods can lead to conflict, potentially leaving some legitimate producers outside the protected zone. Likewise, there’s a philosophical tension between preserving tradition and encouraging innovation. Strict GI rules might lock producers into historical methods, hindering adaptation to new technologies or market trends. Furthermore, the global system is fragmented since different countries use different models (like the EU’s sui generis system versus the US’s trademark approach), creating confusion in international trade.

In the context of Nepal specifically, the challenges are both foundational and practical. Institutionally, the system is inactive. Despite the 2022 Act, a functional GI Registry with technical and legal experts is yet to be established. Along with that, GI success depends on farmers and artisans organizing into cohesive, democratic associations for quality control and marketing which is a difficult task in Nepal’s informal, dispersed sectors. Financially, the costs of certification, marketing, and legal enforcement against counterfeiters, both domestically and abroad, are daunting and require significant upfront investment the state and communities currently lack.

Opportunities for Nepal

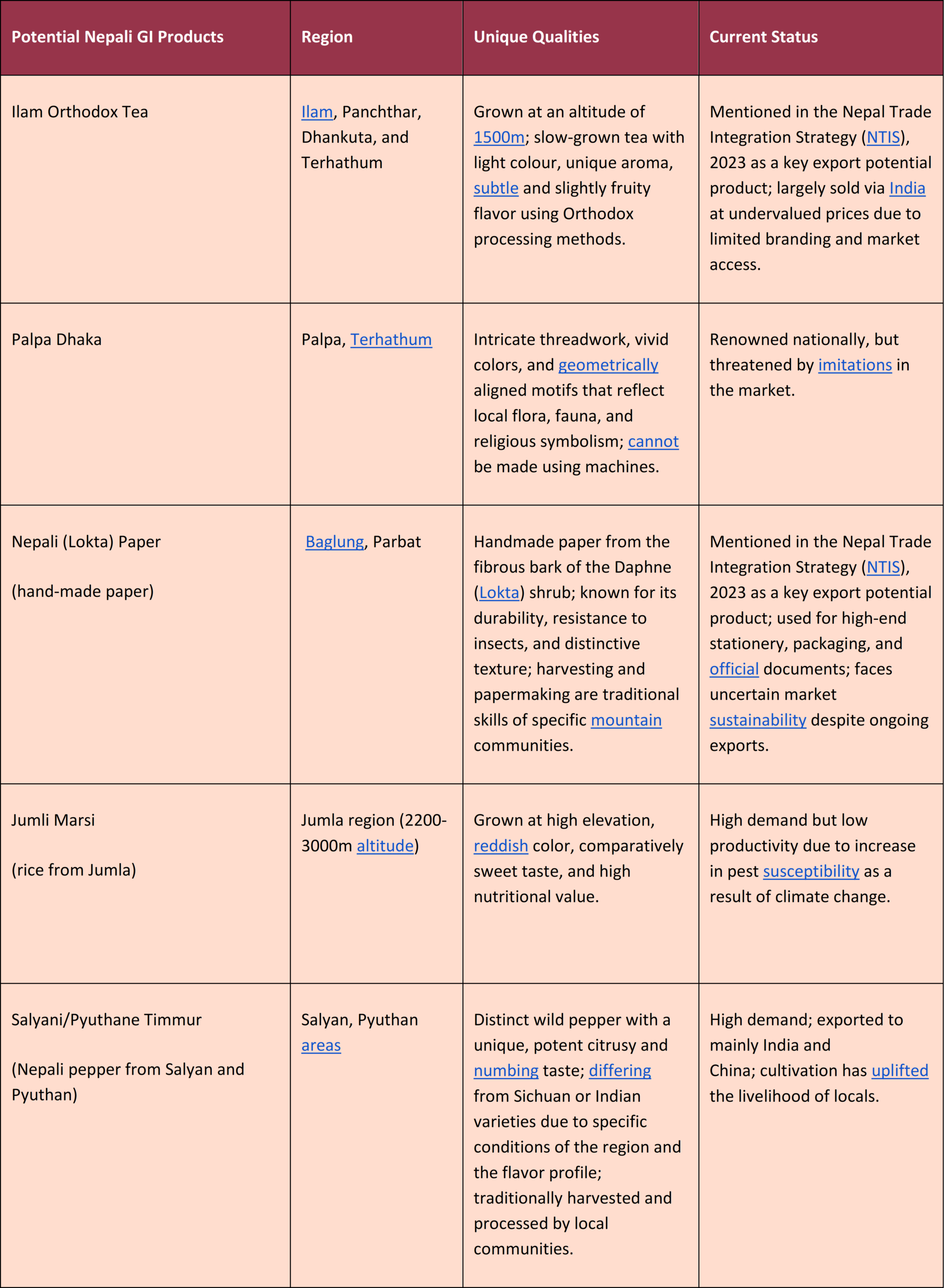

Nepal is a nation blessed with highly diversified climatic conditions which gives rise to a variety of agricultural products. On top of that, it consists of a rich culture, craftsmanship, and artisanal talent, giving rise to unique products such as textile. For Nepal, embracing GI is a strategic opportunity to pivot from selling such authentic yet unbranded commodities to marketing premium experiences. It aligns directly with the nation’s identity of authenticity, craftsmanship, and natural purity. A functional GI system would be a force multiplier for tourism, for high-value agriculture, and for equitable rural development. GI has the immense potential to transform Nepali cultural heritage into a competitive economic advantage. Table 1 depicts some products from Nepal that have potential to get GI-tagged.

Table 1. Nepali Products with Potential for GI-Tagging

Conclusion

The journey for Nepal to claim its GI billions will undoubtedly come with challenges, from legal inertia to mobilization at the grassroot level. Yet, Nepal’s inventory of potential GI treasures is abundant which serves as a great advantage for the country. The cost of inaction is a price Nepal pays daily. To overcome these challenges, stronger legislation and public awareness are necessary. By learning from the successful GI cases of other countries, systematically tackling institutional hurdles, and strategically pushing high-potential products, Nepal can transform its geographical identity from a vulnerable heritage into a powerful economy backed by high-value goods. The opportunity that GI offers to Nepal is not just to protect the past, but to invest in a far more valuable future.

Sampada Regmi is currently working as a research intern at Nepal Economic Forum. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Business Administration (Honors) from Kathmandu University School of Management, and her professional interests lie in international relations, economics, and trade.