Mustang, renowned for its breathtaking landscapes and rich cultural heritage, has undergone a dramatic transformation in recent years. October, traditionally regarded as the best time to visit Mustang, offers perfect weather and stunning scenery, with the bright yellow hues of Bhote peepal trees and colorful carpets of buckwheat flowers painting the region in vivid colors.

Yet, during our field visit to Mustang in the Fall of 2024, we witnessed how this once-bustling hub for trekkers has transformed into a landscape of deserted villages—a stark contrast to its former glory as one of the world’s premier trekking destinations.

The Glory Days of Trekking in Mustang

The 250-km Annapurna Circuit, renowned for the iconic Thorong La Pass, was once hailed as one of the best trekking routes in the world — sometimes even regarded as the single best trek in the world. Spanning five districts — Lamjung, Manang, Mustang, Myagdi, and Kaski — the 23-day trek began in Besisahar, Lamjung, and offered trekkers a journey through diverse altitudes (from around 790m at the lowest point to a stunning 5416m at the Thorong La Pass). The trek was special for its remarkable diversity, presenting a strikingly different shift in vegetation, cultures, and languages, over a relatively short distance. The Thorong La Pass, connecting Manang and Mustang, served as the crown jewel of this challenging yet rewarding adventure.

During its peak, the circuit attracted trekkers from Europe and beyond, significantly contributing to the local economy. Each village along the trail functioned as a vital pitstop, providing food, lodging, and supplies, thereby supporting livelihoods in the region. However, the advent of roads has drastically altered this dynamic.

The Impact of Road Construction

The major road in Mustang is the Kaligandaki corridor which extends from Tansen to the Korala border with China, and is part of the North-South Kaligandaki Corridor. While the development of the road began in 1999, it greatly escalated from 2019, as it was classified as a national pride project by the National Planning Commission. This has greatly enhanced connectivity, offering benefits to both local residents and tourists by facilitating faster travel to multiple destinations. Locals now have better access to healthcare with cities like Pokhara just a few hours away by jeep. Improved ease of transportation has also boosted apple sales from the region. However, while the road has enhanced accessibility and development, its unmanaged construction through trekking trails has drastically shortened the duration of the trekking circuit, reducing itineraries to 10–12 days or even 6–9 days in some cases. Once celebrated as a premier natural adventure trek, the route has largely lost its charm, with nearly the entire route now accessible by jeep, as shown in Figure 1, except for the Thorong La Pass. The road now stretches eastward to Manang and westward to Muktinath, significantly reducing the time required to reach Thorong La Pass.

Figure 1. Map of the Annapurna Circuit

Source: Reworked by Author from Around Annapurna Trekking Map

The locals claim that the roads on both sides of the Thorang La Pass have been constructed without proper planning, often following the easiest path — directly over the original trekking trails. While alternative trekking routes, such as the Natural Annapurna Trekking Trail (NATT), have been developed, they remain under-promoted and are less popular due to their harsh terrain. More importantly, these new routes bypass villages that once served as vital pit stops for trekkers, thereby acting as a major income source for villagers. This shift has diminished the trekking experience, leading to a decline in the number of trekkers and, subsequently, a drop in revenue for local businesses.

The North-South Kaligandaki corridor road has shifted the focus of tourism in Mustang from trekking to pilgrimage and religious tourism. Improved accessibility enables visitors, especially Indian tourists, to reach Muktinath in a single day, often starting at dawn and returning to Pokhara by nightfall. Travel has become so convenient that one can take two short flights from Kathmandu to Pokhara and then to Jomsom, followed by a two-hour jeep ride to the base of Muktinath temple and a brief horse ride up the steep incline to the temple. However, this quick travel pattern provides minimal benefits to the local economy, as tourists now bypass villages like Kagbeni, which once thrived as key stops along the trekking circuit.

Tukuche, once a vibrant center of barter trade between Tibet and Nepal but now a shadow of its former self, is a microcosm of this phenomenon. The village, which once hosted trekkers from across the globe, has been sidelined, with tourists preferring nearby Marpha in recent years. Locals attribute this shift to the increased popularity of Marpha, partly driven by its promotion in the movie Jerry. Today, many residents from Tukuche have migrated to cities or abroad in search of better opportunities, resulting in significant brain drain in Mustang — a phenomenon that reflects the broader pattern across the country but stands out as a particularly acute case in the region. Even local monasteries now struggle with enrollment, relying on students from other Himalayan regions, which raises concerns about the long-term preservation of indigenous cultural practices and the sustainability of local monastic traditions.

The Debate Over Tourism Management

The decline in traditional village life contrasts sharply with the broader tourism management efforts in Upper Mustang. Since opening up to foreigners in 1992, Upper Mustang has required foreign visitors to pay a permit fee of USD 500 per person for the first 10 days, with an additional USD 50 charged per day thereafter. This fee, collected by the Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP), was introduced to safeguard the unique cultural and environmental heritage of Upper Mustang, a remote rain-shadow area beyond the Himalayas, often referred to as the “Forbidden Kingdom”, and particularly applies to the Lomanthang Rural Municipality and Lo-Ghekar Damodarkunda Rural Municipality.

Originally set at USD 700, the permit fee was designed to limit the number of visitors to around 1,000 annually, reflecting the region’s limited infrastructure and efforts to prevent over-tourism. Although the fee was later reduced to USD 500, the construction of new roads has significantly altered tourism dynamics. The Pokhara – Jomsom – Lo Manthang highway, extending to the Chinese border, now allows tourists to complete the trip to Upper Mustang and back in just 3-4 days. As a result, many locals argue that the fee is now disproportionately high, deterring visitors and negatively affecting the local economy.

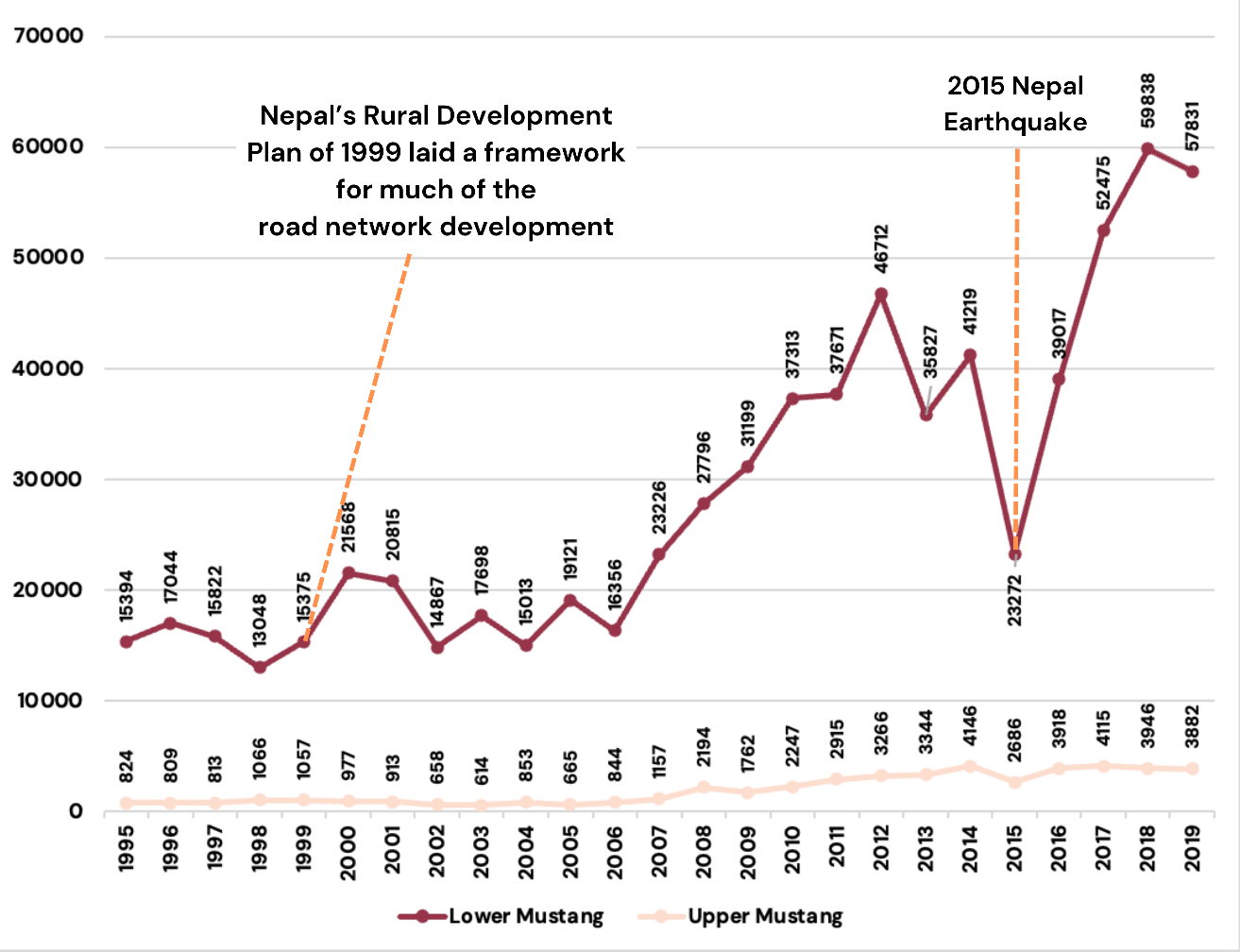

Figure 2. Total Tourist Arrivals in Mustang

Source: ACAP, Unit Conservation Office

This concern is reflected in tourism data since 1995, which shows that the footfall into the Upper Mustang region has remained minimal compared to Lower Mustang. As shown in Figure 2, of the 59,838 tourists visiting Mustang in 2018, only 3,946 ventured into Upper Mustang paying the ACAP premium fee. This figure accounts for just 6.6% of the total tourists in the region that year. Local businesses have felt the impact, as fewer tourists staying for shorter durations contribute less to the local economy.

Thus, the USD 500 permit fee remains a contentious issue. Proponents argue that the fee helps protect Upper Mustang’s fragile cultural heritage and prevents mass tourism that could dilute the region’s identity. Critics, however, highlight the lack of transparency regarding how the revenue is utilized and argue that a lower fee could attract more visitors while still preserving the area’s integrity.

Opportunities Amid Challenges

Despite these challenges, Mustang holds immense potential. The national pride project, the Kaligandaki Corridor, which is currently being blacktopped, offers a direct route linking India and China, positioning Mustang as a strategic gateway for cross-border tourism. Moreover, the road network, while controversial, opens up opportunities for religious tourism. Destinations like Muktinath temple, Damodar Kunda, and Mount Kailash, form a sacred trinity for Hindu pilgrims, which could be leveraged to attract more visitors.

In addition to spiritual tourism, Mustang is well-suited for adventure sports, such as mountain biking, motorbike off-roading, and enduro racing. During our visit, we witnessed the Hero MotoCorp Mystic Mustang Expedition, where over 50 bikes and riders explored the Upper Mustang as part of a promotional event, contributing to tourism and revenue generation. The growing demand for such activities is evident in high-value packages like the lower Mustang mountain biking package, costing up to USD 3,882 per person for a group of four to five participants. These developments underscore Mustang’s capacity to attract adventure enthusiasts and expand its high-value tourism portfolio.

Furthermore, Upper Mustang’s reputation as a “living museum” presents a unique opportunity for niche tourism development. Upper Mustang, also known as the Kingdom of Lo, is renowned for its distinctive culture, dramatic topography, and historical significance. The protected region reflecting Tibetan Buddhism also features the Charang monastery, which claims to house the only collection of the gold-lettered Pragya Paramita, a sacred Buddhist text containing the teachings of Lord Buddha.

Given these possibilities, the region can draw parallels with Bhutan’s high-value, low-volume strategy, an approach that could help preserve Mustang’s rich cultural heritage while fostering sustainable economic growth. This could also include promoting the Tiji Festival, held every May, which epitomizes Upper Mustang’s rich cultural legacy. This three-day celebration features elaborate masked dances and ancient rituals, offering a rare glimpse into centuries-old traditions. The festival’s global appeal is evident, as accommodations often sell out months in advance. However, local residents argue that its significance is still underrecognized within Nepal, highlighting the need for greater domestic promotion. If strategically marketed, events like the Tiji Festival could draw both international and domestic tourists while protecting the region’s identity.

A Path Forward

The transformation of Mustang presents both a cautionary tale and a blueprint for future development in Nepal’s mountain regions. While road construction has altered traditional trekking patterns in the Annapurna circuit and village economies, it has also unveiled new possibilities for tourism diversification. Thus, the region’s success will depend on striking a delicate balance: leveraging improved accessibility to promote sustainable tourism while preserving its unique cultural heritage. This might involve reconsidering the permit fee structure for Upper Mustang, developing targeted marketing strategies for adventure and religious tourism, and ensuring that tourism revenue directly benefits local communities. As Mustang stands at this crucial crossroads, its experience offers valuable lessons for other Himalayan regions facing similar challenges of modernization while striving to preserve their cultural authenticity. Thus, while connectivity through roads and other infrastructure is important, we must ensure that we manage the change in a thoughtful way to create a sustainable future that honors both progress and preservation.

Mahotsav Pradhan holds a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honors) from the University of Delhi. Prior to joining Nepal Economic Forum as a Research Fellow, he has worked as Foreign Exchange Intern at Nepal Rastra Bank. He has a keen interest in development economics, with a passion for exploring the dynamics of policy analysis and international finance.