In FY 2022/23, Nepal’s most-imported product was high-speed diesel, totaling NPR 153.769 billion, which is remarkably close to its total exports of NPR 157.14 billion for the entire year.

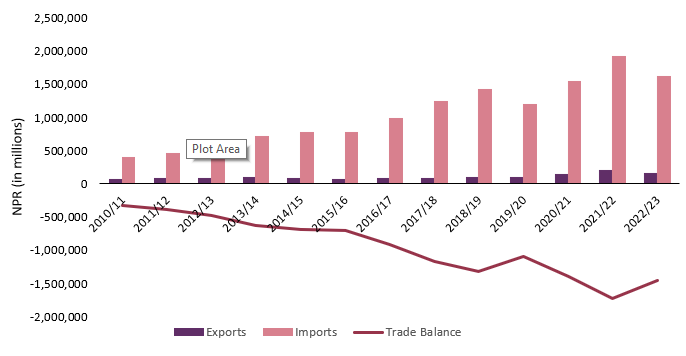

Historically, Nepal has grappled with a substantial trade imbalance, even when it comes to essential goods. In FY 2022/23, Nepal’s exports amounted to NPR 157.140 billion in FY 2022/23, representing only a fraction of its imports totaling NPR 1.611 trillion. This persistent pattern underscores the country’s concerning reliance on imports. Nepal faced a daunting trade deficit of NPR 1.454 trillion in FY 2022/23. In April 2022, the government imposed a ban on various items classified as “luxury goods”, to preserve its depleting forex reserves and control the trade deficit. It remained in effect for seven months till December 2022. While it did lead to an automatic 15.45% reduction in the trade deficit, it also drastically stifled trade activities and government revenue. Further, Nepal’s export earnings had reportedly declined by 21.44% during the same period as well. Government efforts have seemingly failed to have a lasting impact, with Nepal’s trade deficit standing at NPR 115.71 billion in the first month of FY 2023/24.

Figure 1: Nepal’s trade balance from FY 2010/11 to FY 2022/23

Source: Trade and Export Promotion Center, Ministry of Industry Commerce and Supplies

Major Export Products

In FY 2022/23, Nepal’s most-imported product was high-speed diesel, totaling NPR 153.769 billion, which is remarkably close to its total exports for the entire year. In the Nepal Trade Integration Strategy (NTIS) 2023, the government has sought to diversify its exports, with the expansion of the list of promising export products and services to 31 from the previous 12 in the NTIS 2016. In FY 2022/23, export earnings from products identified by the NTIS 2016 reached NPR 48.11 billion. However, only two of these products managed to secure positions among Nepal’s top 5 exported commodities. This article delves into the leading import commodities of FY 2022/23, offering an analysis of potential risks and opportunities associated with each.

Table 1: Top 5 trade commodities in FY 2022/23 (in NPR million)

| Top Exports | Top Imports | ||

| Commodity | Value | Commodity | Value |

| Carpet, knotted of wool or fine animal hair | 11,506.62 | High Speed Diesel | 153,769.98 |

| Refined bleached deodorized palm olein | 10,718.95 | Motor Spirit (Petrol) | 66,844.51 |

| Soybean oil | 8,475.99 | Liquified Petroleum Gas (LPG) | 58,154.11 |

| Large Cardamon (Alaichi), neither crushed nor ground | 8,276.59 | Ferrous products obtained by direct reduction of iron ore | 43,601.77 |

| Palm oil (excl. crude) and its fractions, refined or not but not chemically modified | 6,569.79 | Crude soyabean oil | 35,583.77 |

Source: Trade and Export Promotion Center, Ministry of Industry Commerce and Supplies

Palm and Soybean oil

Palm oil and soybean oil have consistently ranked among Nepal’s top-exported products year after year. However, Nepal does lack any or sufficient farming of palm or soybean for a viable domestic backward linkage. These two oils emerged in Nepal’s export portfolio in 2017 and experienced exponential growth in 2018. Interestingly, the respective crude forms of these oils are also featured among Nepal’s most-imported products, with crude soybean oil ranking as Nepal’s fifth most-imported commodity in FY 2022/23 (Table 1). Nepali traders have been importing crude oils from other countries with minimal tariffs and re-exporting the refined product to India with zero tariffs. They can do so through the South Asian Free Trade Area Agreement, which offers zero tariffs on exports from least-developed countries. While this practice is legally permissible, it diminishes Nepal’s manufacturing potential and has negative connotations for its international trade reputation. Moreover, when a major export commodity relies heavily on re-exports and tariff policies, it becomes vulnerable to external factors and uncertainties, as was the case in 2020 after India imposed restrictions on refined palm oil.

Large Cardamom

In FY 2022/23, Nepal achieved record-high cardamom exports, totaling NPR 8.27 billion. Recognizing the potential of cardamom as an export item, the government has included it in the NTIS and has registered the Everest Big Cardamom trademark to encourage global exports. Despite these efforts, cardamom exports are predominantly limited to Indian markets, where it is re-exported as a high-value product to other South Asian and Middle Eastern countries. India prefers non-processed cardamom due to its lower cost and subsequently engages in processing, packaging, branding, and export activities. Nepal’s lack of direct access to sea routes and reliance on specific Indian routes for trade result in extended transportation times, increased costs, and elevated final prices. Furthermore, Nepali farmers are compelled to send their products to India for testing and certification due to the absence of suitable testing laboratories in Nepal, incurring additional time and expenses. Traders have reported the costs of such verifications to be as high as USD 1,700 per shipment. Moreover, the weak linkages between value chain actors, which have led to fragmented knowledge about the product and its market, are conducive to the poor bargaining power of farmers. Climate change has also exacerbated challenges and expenses related to cardamom farming through as erratic weather patterns and pest infestations become more frequent, which farmers are ill-equipped to address. These factors hinder Nepal’s ability to fully capitalize on its major agriculture exports on a global scale.

Carpets

Nepali woolen carpets have experienced a surge in popularity, with exports valued at NPR 11.50 billion in FY 2022/23. Demand for Nepali products, in general, is reportedly on the rise in the United States and Europe post-COVID. In the 1990s, carpets were a significant source of foreign currency and provided approximately 250,000–300,000 jobs. The mushrooming of carpet producers and the inability to maintain product quality has been listed among the reasons for the decline of carpet exports. Fierce competition in the global market, where people had access to cheaper alternatives, made Nepali carpets appear less attractive. Additionally, the carpet industries faced allegations of poor labor standards and child labor use. As per a 2021 study, child labor use in carpet industries has decreased to 6.6% from 50% in 1993. However, Nepal must consider more factors to sustain the current momentum of the carpet industry. It must ensure proper labor standards and environmental protection guidelines in line with the growing global focus on social and environmental sustainability. Carpet producers have further credited the popularity of their products to the use of high-quality materials. Government support is needed to strengthen the value chain and enhance domestic access to quality materials, thus boosting product competitiveness. Moreover, the absence of adequate laboratories chemical compounds testing in Nepal has forced carpet exporters to seek out costly alternatives.

Outlook

According to a 2021 World Bank report, Nepal’s has the potential to increase its exports by around 12 times. However, realizing this potential necessitates a multifaceted approach, including the modernization of export promotion strategies and substantial investments in quality control infrastructure, among other imperative initiatives. Although government efforts such as the NTIS 2023 exhibit commendable efforts in terms of comprehensiveness and inclusivity, effective implementation is the key. To be able to maximize the effectiveness of any good strategy, it is imperative for Nepal to enhance its coordination, both among various government agencies and with relevant stakeholders. It stands as an essential prerequisite for Nepal to successfully foster domestic innovations and nurture productive businesses, essential to increase its competitiveness in the global marketplace.

Sukeerti Shrestha graduated with a Bachelor's degree in Business Administration (Finance) from Kathmandu University. She's passionate about development economics and sustainability, with a keen interest in using data for decision-making in both business and broader economic contexts. Currently, she works as a Research Fellow at Nepal Economic Forum (NEF), building on her prior experience in management consulting and social enterprises.