At the crack of dawn, a mother quietly gets up and immediately gets to work, while most of the household is still asleep. The chilly early morning air does not stop her from putting the warmth into preparing breakfasts, packing lunches, and setting the household up for a smooth day ahead. As the first rays of the sunlight peek through her kitchen window, she has already worked hard enough, underappreciated and unpaid. These invisible threads woven by mothers, from the early morning constantly hustling till the middle of the night, remain unseen, undervalued, and moreover uncompensated. It is often considered as the ‘default’ expectation placed on mothers by society. Such contributions in forms of direct or indirect care in the household without remuneration are termed unpaid care work, attributed to its exclusion from the national accounts.

Statistics show that 76.2% of the total unpaid care work is performed by women and girls globally. In Nepal, this proportion rises to 86%, accounting for a collective 29 million hours spent in unpaid care work by women – a stark difference compared to the 5 million hours spent by men. This indicates that women in Nepal spend six times more time on unpaid care work compared to men, which highlights a disproportionate burden of unpaid care work in the context of gender. This burden evolves from the ingrained cultural norms, associating men with providing roles and women with nurturing roles, leading to the gender stereotypes existent in the society, often defined in the form of social organization of care.

Why is there a need to care about the Unpaid Care Work in Nepal?

Particularly for women, taking on roles that directly contribute to household income is hampered by devoting a disproportionate amount of time to unpaid caregiving. The Nepal Labor Field Survey 2017/2018 provides evidence on this, with 39.7% of Nepali women citing “unpaid care work” as a key barrier to entering the labour field, compared to 4.6% of Nepali males who mentioned the same issue. The burden posed by the Unpaid Care Work to the women, has been obstructing women from achieving financial independence and social mobility achieved by the participation in the labor force. Even in the cases of women balancing between paid and unpaid care work, the productivity of women at productive sectors declines particularly due to the dual burden of unpaid care and paid work with the constant need to juggle between these sectors.

From a macroeconomic perspective, the efforts and the productivity of these women, who represent almost half of the population, remain ignored in national accounts. The less availability of gender-disaggregated data lowers the perception towards the works undertaken by unpaid care workers, due to its pro bono nature. Consequently, taking women’s work for granted diminishes the total economic contribution made by women and contributes to the lower social standing of women. This tendency of taking these works ‘for granted’ is even more visible in policy failures such as India’s effort to include care work in its national accounts, as it ignored the critical needs of women undertaking unpaid care work and related challenges. ignores the economic as well as social needs and challenges of over the men engaging as full-time unpaid care workers and the dual burdens faced by the ‘working’ women in balancing paid and unpaid care works result in questions on implications of government policies and Sustainable Development Goals aligning with Gender Equality, Decent Work and Reduced Inequalities.

How can we solve this issue?

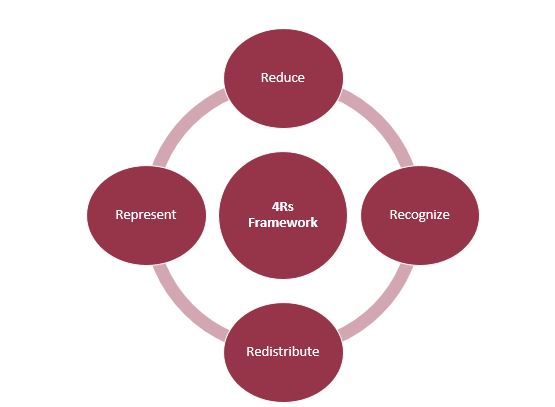

To address the complexities of persistent disproportionality in the distribution of unpaid care work and thereby undervalue the unpaid care work, Oxfam International and Action Aid have proposed a 4Rs Framework of: Recognition, Reduction, Redistribution and Representation for a cohesive, collective response to relieve the work associated with caring work and achieve gender equity.

The first R, focuses on recognizing the unpaid care work in a wider purview, also including the issues in policies and initiatives. As the most primary mechanism for addressing care work, recognition simply refers to making the work visible or acknowledged in the society. A key mechanism utilized to recognize unpaid care work considers providing paid maternity leaves to the new mothers, a concept emerged from Europe and has been applicable in many countries. However, this system still has its own flaws, as exemplified in Finland’s case with concerns regarding the ability for the mothers to return to the workforce effectively after a prolonged leave.

Alongside Recognition, reduction of burden of care work holds greater importance in facilitating effective distribution of unpaid care work. Reduction in forms of enhancing efficiency of the work modules of unpaid care work through installation of technologies like Washing Machines and Dishwashers in urban centers or bringing water source closer to the household as well as use of gas stoves instead of firewood save time for women. This in turn enhances efficiency of the unpaid care workers and help them engage in other economically productive works that would enhance their productivity.

Further, the third R, Redistribution would allow in addressing persistent disproportionality in the household levels with regards to unpaid care work. Redistribution in forms of equitable sharing of the unpaid care works with other family members eventually leading to the shift of excessive unpaid care work to others, reducing the burden by tackling entrenched stereotypes. A prime example of this would be the redistribution of care work in Nordic countries, wherein paternal leave and father’s quota is deemed to be effective in redistributing unpaid care work, promoting better opportunities for paid work for women.

Lastly, Representation in forms of engaging caretakers in policy development process, ensures inclusive decision making, addressing their needs and challenges. This can ensured by promoting social dialogue and collective bargaining for care workers. For instance, greater representation of women caretakers in the policymaking in Nordic countries can be considered as a case for developing paternal leave and father’s quota policies, which are effective in ensuring reducing and redistributing care work.

Source: Author’s Generation Utilizing Flat Icons

Outlook

Tackling unpaid care work remains an integral part particularly in achieving gender equality and tackling gender dis appropriation in unpaid care work. Visible formation of lower women’s participation in workforce is hampered by the invisible labor of unpaid care work which leads to its undervaluation and underappreciation. This not only restricts the economic prospects and potentials of the unpaid caretakers but also shapes perceptions towards them by the society also attributed to their social status and autonomy given their underrecognition. Recognizing the role that Nepali women play in the disproportionate amount of unpaid care labour is an imperative need to achieve gender equality, especially in the social and economic domains. Based on this, it seems that adhering to the 4Rs Framework will be both necessary and fascinating to assist the women who are compelled to provide unpaid care in realizing their full potential and enhancing their economic and social contributions by strengthening their social status.

Pransu Khakurel holds an MSc. in Gender and Development Studies from Asian Institute of Technology, Thailand. Prior to her engagement as a consultant at Nepal Economic Forum and beed Management, she worked in non-profit sector for 4 years in Project Management and Development Communications. Her deep interest lies in researching on Feminist Economics with inclination on Care Economy and Effects on Migration.