The weeks leading up to the festive seasons of Dashain and Tihar are always marked with clear skies, pleasantly cold weather, gentle winds, and the cheerful bustle of households preparing for celebrations. However, last year was entirely different. Instead of blue skies, there was relentless rain. Instead of gentle winds, there were rivers devouring roads and houses; mud-plastered legs fleeing rising waters; and cars floating around like debris. And what awaited wasn’t festivities, but rather a climate disaster.

This was the scene in Nepal following two days of relentless rain from September 26 to 28, 2024. These unprecedented, late monsoon rains caused severe flooding and devastating landslides across Nepal, resulting in significant infrastructure damage, disruption of industries and, unfortunately, loss of lives. This article explores the economic toll of the September 2024 floods, what caused them, the government’s response, and what is needed to prevent such disasters in the future.

Impact in Numbers

The September rains was the most severe rainfall Nepal experienced in the last four decades. These rains, and the consequent flooding, caused extensive damage across various sectors, impacting many people. According to a recent World Bank report, the flooding led to 249 deaths, 177 injuries, and the displacement of more than 10,000 families. Furthermore, an additional 16,241 families were affected due to housing damages. In fact, 5,996 houses were completely destroyed and 13,049 were partially damaged. A significant portion of the impact was concentrated in Bagmati, making it the most severely affected province. Additionally, vulnerable groups, such as low-income households and slum dwellers, were disproportionately affected, further concentrating the impact.

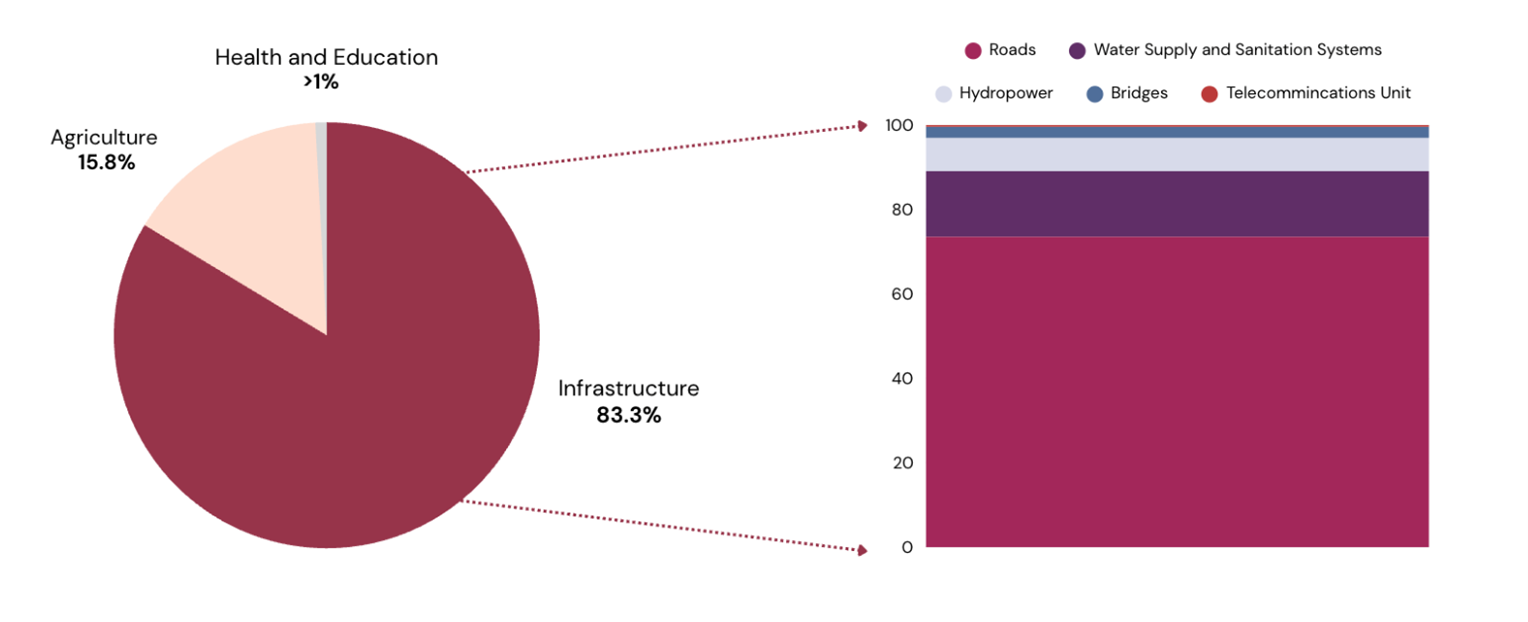

Figure 1. Sectoral Distribution of Damages

Source: Nepal Development Update, World Bank, April 2024.

The total losses caused by the floods are estimated to be around NPR 46.7 billion, spread across four sectors: infrastructure, agriculture, health, and education. Within infrastructure, road damages resulted in the highest loss due to landslides, soil erosion, severe heaving and cracking. In fact 41 roads, within and outside of Kathmandu Valley, were completely damaged and blocked. Furthermore, water supply sanitation systems, hydropower facilities, bridges and telecommunications units were also severely affected. Meanwhile agricultural losses were primarily due to swamped farmlands, destruction of crops, and livestock casualties. An assessment revealed that 65,380 hectares of agricultural land, 26,698 livestock, and seven irrigation projects were considerably affected. Lastly, the education sector and health sector experienced significantly loss, predominantly due to disruption of services and damages to schools and health facilities. For example, Mediciti Hospital experienced complete flooding of its lower floor due to the overflowing of the Nakkhu River located close to its proximity, damaging medical equipment and causing partial shutdown.

Breaking Down the Causes

Although the numbers above highlight the damage inflicted by the September floods, they do not paint the entire picture. To understand how such extensive damages could occur in just two days, it is important to examine the factors that caused both the unprecedented rainfall and the consequential floods.

The scale of the September 2024 floods was unlike any in recent history. During the floods, Kathmandu Valley experienced almost 9.5 inches of rain, and rainfall across the country was 22% higher than the average during that specific season. Besides, the 2024 monsoon season lasted two weeks longer than the average monsoon period of 112 days. These floods demonstrate a primary consequence of climate change and global warming: an intensification of both wet and dry seasons. Hyperbolic monsoon rains and winter droughts, due to rising temperatures, create severe weather phenomena such as the floods of 2024. Unsurprisingly, the winter following the floods was one of the driest winters experienced in Nepal, perfectly illustrating the climate volatility created by climate change.

The effects of such extreme climate conditions were further exacerbated by the city’s poor drainage systems and haphazard urban planning. According to experts, encroachment of the river basin due to the unregulated construction of thousands of houses and roads over the past four decades was a key reason the floods caused such extensive damage. Furthermore, the concrete and asphalt utilized in construction restrained excess water from being absorbed by Kathmandu’s otherwise porous soil, which led to huge runoffs and flooding across inner city areas. Additionally, the existing flood prevention infrastructure struggled to manage any excess water, largely due to blockages from improper solid waste disposal and aging drainage systems. Overall, encroachment and the lack of flood prevention mechanisms, paired with the waste and congestion generated by the growing urban population, gradually caused the city to inevitably turn into a flooding basin during the extreme 2024 rainfall.

To top it off, a lack of initiative was evident in the inaction of the local and federal government despite a warning raised by the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology regarding flash floods and severe rains, three days prior to the incident. Even with the “Monsoon Preparedness and Response National Action Plan, 2081”, steps were not taken to warn and evacuate individuals and families in disaster-prone areas like the river banks and areas prone to waterlogging. This oversight from key stakeholders led to more losses than necessary, some of which could have been mitigated if proper measures had been taken.

Relief Efforts and Governance Challenges

The federal and provincial governments took certain reactive measures to mitigate damages and support the impacted population. These include both rescue measures as well as financial support for necessities and infrastructure recovery. 30,371 security personnel were deployed across the valley to perform search and rescue operations and helicopters were deployed to rescue more than 900 individuals stuck on rooftops or precarious areas. Furthermore, to provide affected communities with food, shelter and other necessities, the Bagmati provincial government distributed NPR 58 million to its 45 municipalities. Progressively, roads, hydropower plants, telecommunication units, and other infrastructure were rebuilt, with the majority now back in operation.

Financial support was also provided by various development institutions to expedite relief efforts. Organizations like the Nepal Red Cross Society (NRCS) helped provide USD 520,000 in order to support ongoing efforts. In addition, the World Bank approved a USD 150 million financing facility that can be utilized in case of floods and other disasters like the one in September 2024.

However, despite support from international organizations and the government’s internal capacities, there have been gaps in the response measures taken. For example, although the government mobilized security personnel, they lacked the equipment to carry out rescue operations effectively. Rescue personnel were seen using primitive equipment like rubber boats, ropes, tubes, and shovels, thereby delaying timely rescue. Moreover, despite rescue measures, many people remained stranded, ultimately facing injuries or getting swept away.

The government also faced criticism regarding the lack of proper urban planning. The crux of the matter is that the government has frequently failed to implement and update the necessary infrastructure for the increasingly urbanized and climate-vulnerable Nepal. For example, the current drainage systems in Kathmandu were constructed to meet the needs of previous weather patterns and a smaller population. But with growing urbanization and climate extremes, these existing systems are now inadequate, leading to frequent road flooding. While the government has taken reactive measures, the lack of preventive measures, such as implementing climate-resilient infrastructure, has created a cycle of crisis and response instead of avoiding crisis altogether.

However, the government is not entirely to blame. Infrastructural changes such as updating drainage systems, creating flood barriers, etc., are often resisted by homeowners, squatters, and other stakeholders. For example, the Supreme Court mandated an increased 20-meter buffer between rivers and surrounding buildings. This was intensely opposed by the private sector, particularly real estate developers. Additionally, Prime Minister KP Oli voiced his disapproval for this ruling stating it could wipe out numerous residences of people, leading to the ruling being eventually revoked. Such public pushback to beneficial policies and infrastructural changes highlights the multilayer nature of climate disaster prevention and crisis management. Building climate-resilient cities is a complex endeavor that requires balancing the interests of a multitude of stakeholders. Moreover, even with existing urban planning and construction policies, citizens often neglect following proper procedure and build houses that encroach on public property or natural resources. In fact, Mayor Balen Shah in recent years has been seen taking a firm stance against such violations, going as far as to breaking down encroaching buildings.

Way Forward

Although the severity and timing of the September 2024 floods were unusual, general flooding has consistently plagued Nepal. With increasing climate change effects, such extreme events are bound to transform from a one-off nightmare to a frequent reality. In fact, according to The World Bank, floods in Nepal have already doubled in recent years. Therefore, the government must begin adopting preventative measures to deter extreme weather events from evolving to complete crises. Measures such as effective early warning systems, climate resilient infrastructure (roads, barriers, etc.), updated drainage pathways and land zoning and use regulation are a few of the most important prevention mechanisms the government must immediately implement. Additionally, the government must strengthen pre-existing reactive measures through the improvement of rescue equipment and more effective use and timely deployment of emergency funds. With the budget for FY 2025/26 AD forthcoming, and planning already underway, there must be specific allocations and strategies provided for the implementation of these measures, to be better prepared for the approaching monsoon. Furthermore, Nepali citizens can be better prepared by staying informed during crises by following government portals (BIPAD), building flood-proof homes, preparing emergency kits, purchasing flood insurance, and following urban planning guidelines. Only through a coordinated effort between government action and citizen preparedness can Nepal hope to minimize the devastating impacts of future floods.

The months leading up to the winter season have always been filled with tika-stained foreheads and houses covered in twinkling stitchery, celebrating the retreat of monsoon and the beginning of a fruitful harvest. With adequate preparation, may this coming monsoon not be marked by chaos and loss, but rather the riverdance between wild laughter and the rhythm of the madal.

Tanisha KC holds a BA in Economics from UMass Amherst, with a deep commitment to policy reform, sustainable development, and fostering inclusive economic growth. Driven by the belief that writing can be a powerful tool for change, she is currently interning at the Nepal Economic Forum. Tanisha is eager to sharpen her writing skills, immerse herself in the Nepali economy, and contribute to meaningful economic discourse that drives real-world impact.