Economies around the world have shown an increasing interest in alternative energy sources in an attempt to reduce GHG emissions and fuel sustainability. This gives Nepal an opportunity to capitalize on its rich water resources for hydropower generation. Evidently so, in recent years, these water reserves have become a competitive resource due to the growing bilateral and international interest in hydropower projects, raising concerns about the underlying motives of influence and control. Known as the yam between two boulders, Nepal can draw from its strategic geopolitical positioning in South Asia for promoting sustainable energy production in the region.

Harnessing Hydropower Potential in Nepal

Nepal’s hydropower potential has been theoretically estimated to be 83,000 MW, and the economically feasible potential has been evaluated at around 43,000 MW. Despite this, the country’s installed hydropower capacity currently stands at around 2,800 MW. While Nepal had an early start into hydropower production with the 500 MW Pharping Hydropower Plant in 1911, it has been unable to utilize it to its full extent. Today, there are a total of 149 hydro projects in the country with a capacity of 1 MW or above. In 2023, Nepal produced 10,536 GWh, of which 9,358 GWh was consumed domestically, 1,348 GWh was exported to India for the first time, and 1,665 GWh was wasted surplus.

With a target of producing over 28,000 MW and exporting 15,000 MW by 2035, Nepal aims to leverage its hydropower by boosting its energy production, enhancing cross-border transmission infrastructure and exporting surplus electricity to expand the market. A notable step in energy export development is the upcoming tripartite agreement on July 28, 2024, allowing Nepal to export 40 MW of electricity to Bangladesh via the 400 kV substation at Muzaffarpur, India.

Neighborly Presence in Energy Sector

Sandwiched between India and China, Nepal benefits from the presence of these neighboring giants. This is evident in the investments flowing into Nepal across various sectors, including energy. China first showed interest in Nepal’s hydropower sector around 2010. It coincided with Nepal’s further liberalization of the sector for private investments under the 1992 Electricity Act, which opened up more investment opportunities and strengthened the energy relationship between Nepal and China. In the present day, China is considering funding the Tamor hydroelectric project (762 MW) and the Galchhi-Rasuwagadhi-Kerung 400kV transmission line under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). These are strategic moves to enhance regional connectivity and infrastructure knowing the fact the shared Himalayan border is geographically very challenging to trade electricity.

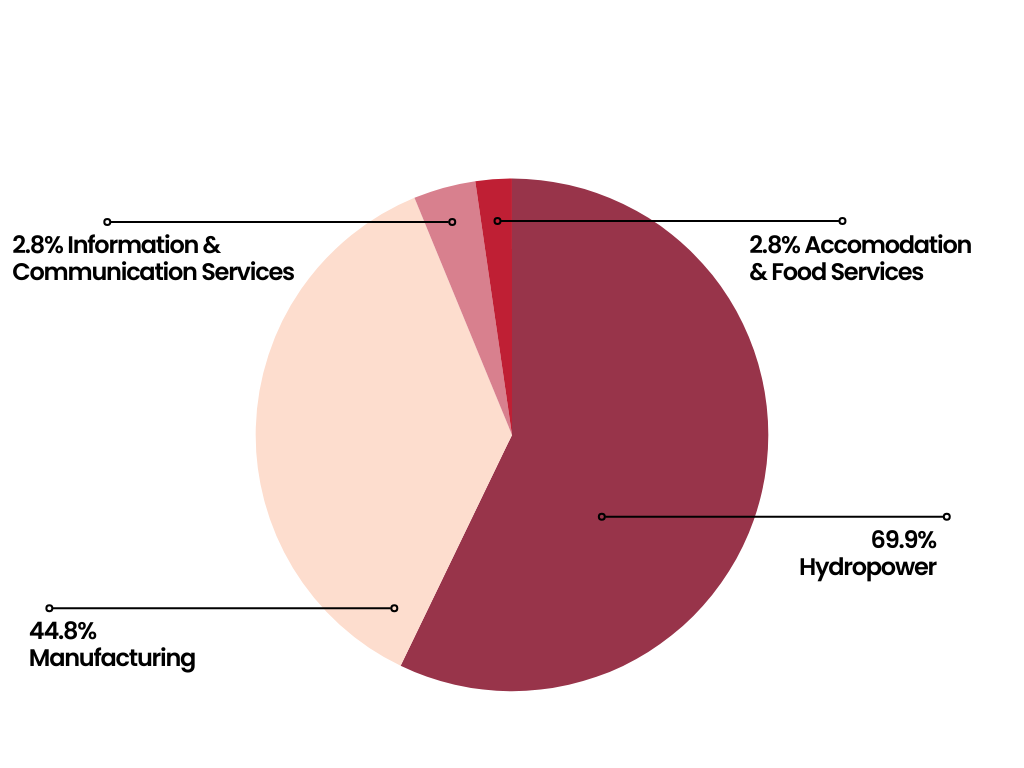

Figure 1. Share of China’s FDI Stock in Nepal (%)

Source: Field Survey 2023, Nepal Rastra Bank

Similarly, India and Nepal share very close historical, cultural, religious, and socioeconomic relations that form the bedrock of their ties. Nepal’s energy sector has long been intertwined with India’s. Currently, India is the sole country importing electricity from Nepal, and also supplies electricity to Nepal during the dry season. In 2019, over half of Nepal’s electricity needs were met through imports from India. However, India’s role as a key energy supplier comes with its challenges. India has occasionally been unreliable, such as delaying the Nepal-India medium-term electricity trade agreement in 2024, citing the Lok Sabha elections. Despite these issues, Nepal has complied due to India’s importance to its energy market. India has further been seeking to highlight its presence in Nepal’s energy sector through big long-term projects, such as the 10,000 MW power export deal from Nepal, which blocks China out since all these exports do not include electricity generated by Chinese-funded hydropower projects.

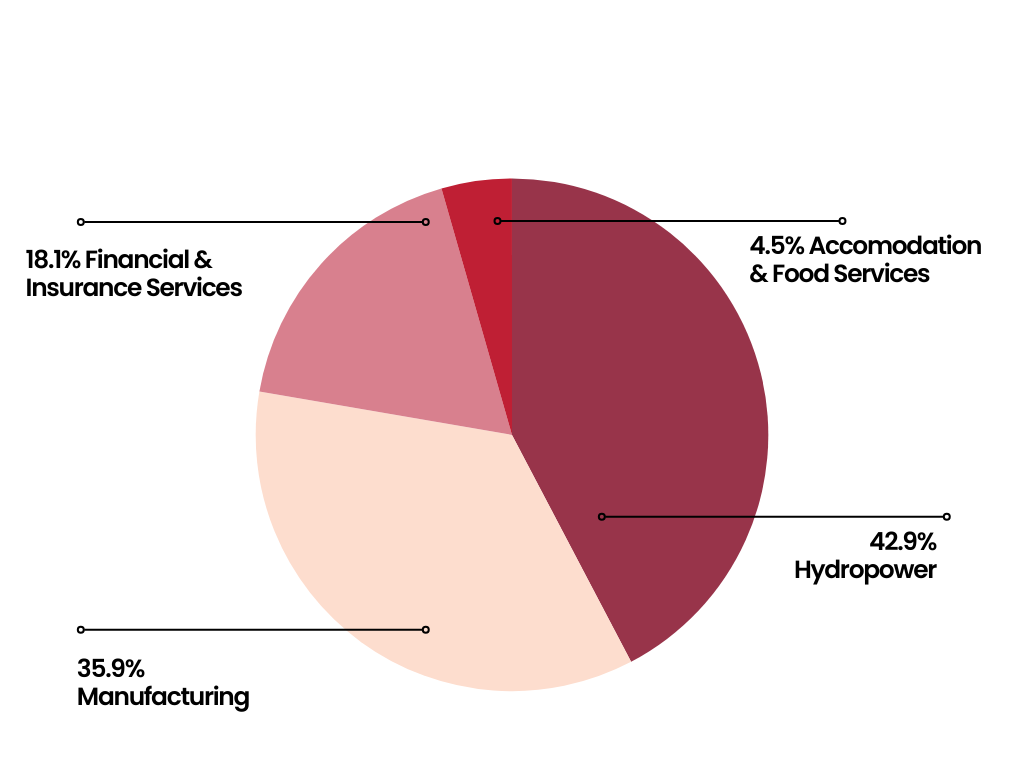

Figure 2. Share of India’s FDI Stock in Nepal (%)

Source: Field Survey 2023, Nepal Rastra Bank

Geopolitics of Power Trade

In 2018, India changed its policies to prevent the purchase of power produced via the investment of nations with which it does not have a “bilateral agreement on power sector cooperation”. This means India and its companies cannot buy hydropower electricity produced by Chinese-funded or Chinese-built power plants. Consequently, India is yet to grant the approval for export of hydroelectricity generated by several projects including Nepal’s flagship Upper Tamakoshi Hydropower Project (456 MW) that became operational in July 2021, allegedly on the grounds of Chinese involvement. Such policies can significantly discourage Chinese investment in Nepal’s hydro projects and limit China-Nepal cooperation on water resources. Second, it influences Nepal to provide construction licenses to Indian companies and contractors or else risks losing investment in water resources. As a result, hydropower projects in Nepal will see increased Indian involvement with other countries’ stakeholders being discouraged.

The repercussions of this power purchasing shift are already evident. Nepal has removed Chinese developers from six hydropower projects and given four hydro contracts to Indian companies. Indian companies now have contracts to build and operate 10 hydropower plants in Nepal, while Chinese developers have such contracts for only five projects. This can have a tremendous effect in Nepal because as a power surplus country, it needs to find overseas markets for its surplus electricity during the rainy season. Currently, India is the sole importer and Nepal is seeking to formalize an energy trade agreement with Bangladesh. The fact that it requires India’s cooperation is a testament to the central role India plays in Nepal’s energy sector, even when it comes to diversifying the market. Another leverage India has is Nepal’s reliance on India during dry seasons to meet its electricity demands. As Nepal’s hydropower infrastructure lacks a storage system, the excess energy created during the wet seasons go to waste. With Nepal-China electricity trade yet to transpire, not cooperating with India puts Nepal at risk of losing current and future export opportunities.

Such politically driven actions show larger implications within environmental and community aspects of the involved regions. Particularly with transboundary water resources, India’s construction of dams and embankments near the Nepal-India border has led to severe flooding in Nepal, affecting thousands of families and submerging over 6,800 hectares of land in Saptari and Sunsari districts. Similarly, China’s control over upstream portions of major rivers like the Brahmaputra poses significant challenges for India’s water security, potentially reducing water availability and harming agriculture for over 600 million people. Sudden water releases from Chinese dams can cause flooding, exacerbating natural disasters in Indian states like Assam. Additionally, changes in sediment flow due to these dams reduce soil fertility, lowering agricultural productivity in India. The lack of comprehensive water-sharing agreements further increases mistrust and geopolitical tensions.

Outlook

Nepal should prioritize making financially shrewd decisions while carefully navigating its geopolitical implications. India’s investment and willingness to import is a significant opportunity for Nepal, through which Nepal could leverage its geopolitical location by diversifying its market, promoting regional cooperation and attracting global investments. Another factor Nepal should be cautious of, as a Himalayan nation relying on hydropower, is how climate change can alter water availability. It necessitates cooperative water management and formal agreements to mitigate these adverse environmental impacts and ensure regional stability.

Although Nepal’s future economic growth relies on securing a foreign market, it hinges equally on building a robust domestic market for electricity. It is important for Nepal to first prioritize meeting its domestic demands and being able to provide a stable supply of electricity. In the same vein, establishing storage systems to address the severe seasonal fluctuations, would ensure optimal grid stability and maximizes energy utilization efficiency. Such infrastructure is a must for a country whose hydro-sources are marked by surplus in the rainy season and diminished output in the drier seasons.

Samragyi Karki is an undergraduate student majoring in Economics. She has prior experience in banking, real estate, and marketing sectors in Nepal. She is currently exploring sustainable development, given her enthusiasm for climate activism, and enjoys understanding the ways in which society operates.