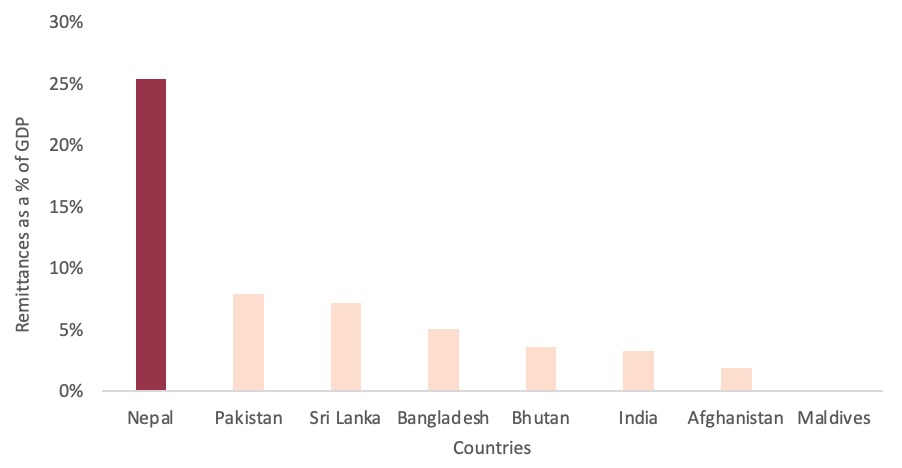

In FY 2023/24 AD (2080/81 BS), Nepal received more than NPR 1.4 trillion (USD 10.2 billion) — a quarter of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) — in remittances, providing critical financial support for everything from school fees and rent to groceries and medical care. Nepal consistently ranks as the top country in South Asia in terms of remittances as a percentage of GDP (Figure 1). But behind this economic figure lies a complex human story of a diverse and dispersed diaspora, with more than 2.1 million Nepali citizens abroad according to government sources and estimates of closer to 4.5 million when also considering foreign nationals of Nepali origin.

Figure 1. Countries in South Asia by remittances as a share of GDP

Source: World Bank

Source: World Bank

In Nepal’s policy discourse, the diaspora is often treated primarily as a source of financial inflows or capital investment. This economic lens often obscures the sociological realities of diaspora communities, composed of individuals and families with enduring cultural and emotional ties to their homeland. As patterns of migration shift from being dominated by temporary labor contracts to increasing instances of long-term settlement abroad, Nepal must re-examine its understanding of who constitutes the diaspora and their rights and recognition.

International Definitions of the Diaspora

There is no one universal meaning of ‘diaspora’, with international organizations and governments adopting a range of definitions.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) defines diasporas as “individuals and members of networks, associations, and communities who have left their country of origin but maintain links with their homeland.” This broad definition includes permanent expatriate communities, temporary migrant workers, dual nationals, and descendants who have kept their ties with the homeland. The African Union defines the African diaspora as “consisting of people of African origin living outside the continent, irrespective of their citizenship and nationality, and who are willing to contribute to the development of the continent and the building of the African Union”, emphasizing that diaspora members have a stake in their homeland’s development.

On the other hand, India categorizes its diaspora into Non-Resident Indians (NRIs), citizens of India residing abroad, and Overseas Citizens of India (OCIs) i.e. foreign nationals descended from Indian citizens (up to the fourth generation) who get the right to live, work, buy property and invest in India but do not have voting rights or eligibility for public office. Meanwhile, the Philippines uses the term ‘Overseas Filipino’ to describe persons of Filipino origin living outside the Philippines, including both citizens and those with ancestry, without a formal generational cut-off. Ireland is even more inclusive, defining the diaspora as all those of Irish heritage abroad and allowing citizenship by descent if you have even just one grandparent born in Ireland.

In general, international institutions usually define the diaspora by focusing on self-identity and emotional connections, while countries tend to be concerned with the balance of economic and political rights.

Nepal’s Legal Framework

Nepal’s diaspora policy is codified under the Non-Resident Nepali Act (2008). The law distinguishes between:

- Non-Resident Nepalis (NRNs): Nepali citizens who have resided abroad for more than two years (excluding in SAARC countries); and

- Foreign Citizens of Nepali Origin: Foreign nationals who once held Nepali citizenship or whose parents or grandparents did.

Under the Act, NRNs can inherit some property, open bank accounts, make investments, and enjoy concessional visa access. However, they are barred from holding political office or voting in elections.

The 2015 Constitution also introduced a provision for NRN Citizenship, which could be granted to a foreign national “whose father or mother, grandfather or grandmother was previously a citizen of Nepal”. However, enabling legislation was only introduced in 2022 and the Act passed in 2023. Implementation, meanwhile, has still been marred by bureaucratic delays and conflicting provisions, such as a promised 10-year visa term being changed to a two-year renewal cycle.

These constraints reflect Nepal’s tendency to engage with its diaspora chiefly through an economic lens while withholding social and political inclusion. While the legal framework outlines who qualifies for rights, it does not fully address the deeper question of identity. The diaspora is often viewed more as a financial resource than as a community with voice, identity and heritage. This raises a set of difficult and important questions, which cannot be definitively answered but at least provide some food for thought: Who counts as the diaspora? Is it just simply a matter of citizenship or ancestry? Can connections be maintained over time and across generations, and how should they be recognized?

Diving into the academic history of the concept of the diaspora can help tackle some of these questions.

Academic Conceptualizations

The word “diaspora” comes from the Greek word “diaspeirein”, which means “to scatter”, and was originally used to describe communities forcibly displaced from their homelands. Safran (1991) conceptualized a diaspora as an expatriate community pushed out from an original center, which maintains a collective memory or myth about the homeland and regards it as a place of eventual return. On the other hand, Cohen (1997) argued that the definition should be more flexible because migration can also be voluntary, and diaspora groups may partly assimilate into host societies. He proposed a typology beyond the ‘victim’ model, outlining ‘labor’ diasporas driven by economic migration, ‘trade’ diasporas comprising of historical merchant traders and ‘settler’ diasporas of colonial populations settling in new lands.

Meanwhile, Brubaker (2005) argued that applying the term diaspora to any group living outside its ancestral homeland potentially dilutes its meaning, distilling the concept to three core elements which distinguishes a diaspora from an ‘expatriate network’:

- A dispersed population, spread from a homeland to at least two other regions;

- An orientation towards an actual or imagined homeland, which remains a source of value and identity; and

- Some degree of boundary maintenance, such that the group sustains a distinct identity over time.

What Does ‘Diaspora’ Mean for Nepal?

Many of these definitions are built on self-identification whereby a person is part of a diaspora if they feel and claim that identity, not simply by blood or language. In the Nepali context, migration was historically linked with the British East India Company which recruited Nepali workers to India (especially the Northeast), Bhutan, Myanmar, even Thailand and Fiji. These groups have ancestry from Nepal, and many still speak Nepali, but they should not be counted as the diaspora because they often identify more with their host country than with Nepal.

What about a third-generation Nepali who has grown up overseas and does not speak fluently? Some argue that the diaspora identity necessarily fades after a few generations of assimilation. But to resign oneself to this fate is to miss out on the opportunity to make an impact. Diaspora identity can be revived in later generations, who might be committed to learning about their roots. Being part of the diaspora is less about the number of generations as it is about socialization to keep language, heritage and culture alive — and this should be encouraged as much as possible.

Why Defining the Diaspora Matters

Creating a definition of the diaspora has profound implications for how a state builds relationships with its citizens and descendants abroad. Different countries approach this challenge in different ways. India’s Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) model offers economic and residency rights to foreign nationals of Indian ancestry for up to four generations, in line with the general profile of the Indian diaspora as economic migrants. Ireland, with a more liberal understanding of its diaspora, grants citizenship by descent on generous terms and has recently launched a ‘Global Irish’ survey to map the diaspora. France and Italy reserve parliamentary constituencies for overseas voters, and countries such as Armenia and Israel, who typify the ‘forced dispersion’ profile, have a Minister or other senior government official tasked with engaging with the diaspora.

At the heart of a relationship between the state and the diaspora is mutual expectations. States often seek economic capital in the form of remittances and investment, human capital through knowledge transfers, and soft power through cultural diplomacy or advocacy. Diaspora communities seek recognition, cultural belonging and the ability to participate in their homeland’s future.

Balancing these interests requires clarity about who is included. Nepal’s approach tends to view the diaspora through an economic lens, valuing financial contributions whilst hesitating to extend social or political rights. NRNs, many of whom are highly educated, wealthy and committed to Nepal, have raised concerns about legal ambiguities and bureaucratic hurdles. Recent moves to grant NRN citizenship remain unimplemented, with reports of delays and inconsistent provisions.

A more expansive, identity-based definition that is grounded in self-identification, cultural connection and a willingness to engage would allow Nepal to build a strong two-way relationship.

Conclusion

Cultural belonging often outlasts legal recognition. Many Nepalis abroad, including those with no recognized status in Nepal, continue to celebrate festivals, speak the language, and support Nepal. These emotional and cultural ties offer a powerful foundation for long-term engagement. But without corresponding institutional recognition, especially for later generations, the connection risks fading over time. A diaspora left unacknowledged may grow distant, not because of a loss of sentiment, but because the structures to sustain it are missing.

Nepal has made important strides in recognizing its diaspora, but continues to see them primarily as economic agents rather than social actors. To build a more durable, multi-generational relationship, Nepal must reframe the way it defines and engages with its global citizens.

Rojan Joshi is an Economics and Finance student at the Australian National University, Canberra. He is interested in international economics and public policy, with experience across government, academia, think tanks and the private sector in Australia, India and Nepal.