How poor is Nepal?

Nepal, a country known for its diverse culture and stunning landscapes, continues to grapple with significant poverty challenges. Despite efforts through government investments and some progress over the years, poverty still remains a pressing issue for Nepal. The Fourth Nepal Living Standards Survey (NLSS-IV) indicates that 20.27% of the population still lives below the poverty line, a slight decrease from 25.16% in 2011. Rural areas are more affected, with a poverty rate of 24.66% compared to 18.34% in urban areas. This means that over one-fifth of the population, or approximately 5.9 million people, are still unable to meet their basic needs like food and shelter. Although Nepal has been reducing its poverty rate from 41.8% in 1996, Nepal still ranks among the poorest country in the world with GDP per capita of USD 5,032 (NPR 673,571.36) and second only to Afghanistan in South Asia.

The measure of poverty

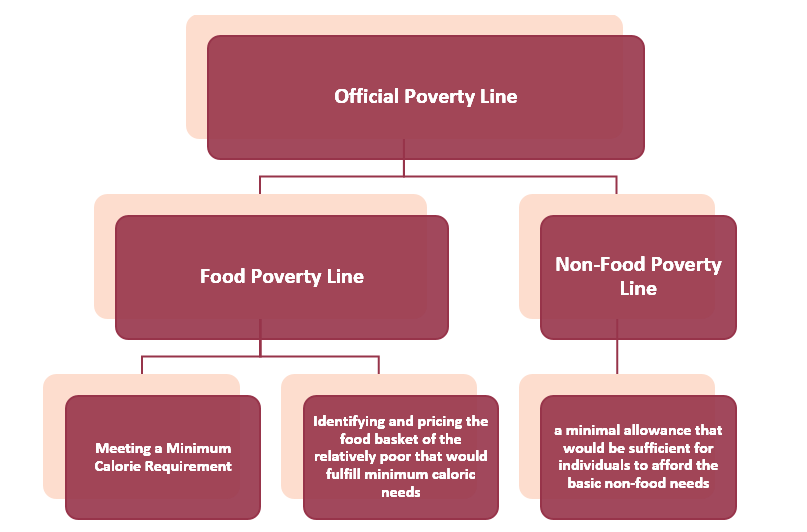

Like in other countries in the South Asia, the poverty line in Nepal is defined by Cost of Basic Needs Approach, which is the minimum expenditure needed by an individual to fulfill their basic food and non-food needs. The poverty line for Nepal is currently defined on whether a person can spend at least NPR 72,908 (USD 544.73) annually on daily food and non-food essentials. The poverty rate would have been only 3.57% if the annual income threshold was kept at the level of the 2011 survey, which was NPR 19,261 (USD 146.55). The 2011 rate was adjusted for inflation to NPR 42,845 (USD 320.02) but was further revised to NPR 72,908 (USD 544.73) taking into account international standards for poverty and improvements in consumption patterns.

Figure 1: Estimation of the National Poverty Line

Source: Nepal Living Standards Survey-IV 2022-23, NSO

Nepal has shown progress in reducing multidimensional poverty, which considers such as child mortality, primary school completion rates or undernourishment, and trends of income poverty. According to Nepal’s official Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), the percentage of multidimensionally poor individuals decreased from 30.1% in 2014 to 17.4% in 2019. This positive trend suggests improvements in education, healthcare, and living standards. However, significant challenges remain, as 4.9 million people are still multidimensionally poor, deprived of housing materials, clean cooking fuel, years of schooling, assets, and nutrition.

Moreover, the international poverty line, which serves as a benchmark for extreme global poverty, was recently adjusted to USD 2.15 per day (NPR 287.85), replacing the previous USD 1.90 (NPR 254.59). The World Bank’s absolute poverty line indicates that individuals below this threshold lack the resources for basic necessities like education and health. The official revised monetary poverty line is NPR 72,908 (USD 544.73) which approximates to NPR 199.75 (USD 1.49) per day. Nepal’s poverty line is lower than the global average of extreme poverty of USD 2.15, highlighting the severity of poverty in the country.

What does it mean to be poor?

Nobel laureate Amartya Sen states that poverty is not merely the absence of money but the inability to fulfill one’s potential due to lack of basic necessities and opportunities. In Nepal, the consumption-based poverty line fails to capture these broader dimensions, leading to a narrow understanding of poverty. According to NLSS-IV, the average annual spending on consumption rose by 66% in the past 12 years, reaching to NPR 126,172 (USD 942.47) in 2023 from NPR 75,902 (USD 567.05) in 2011.

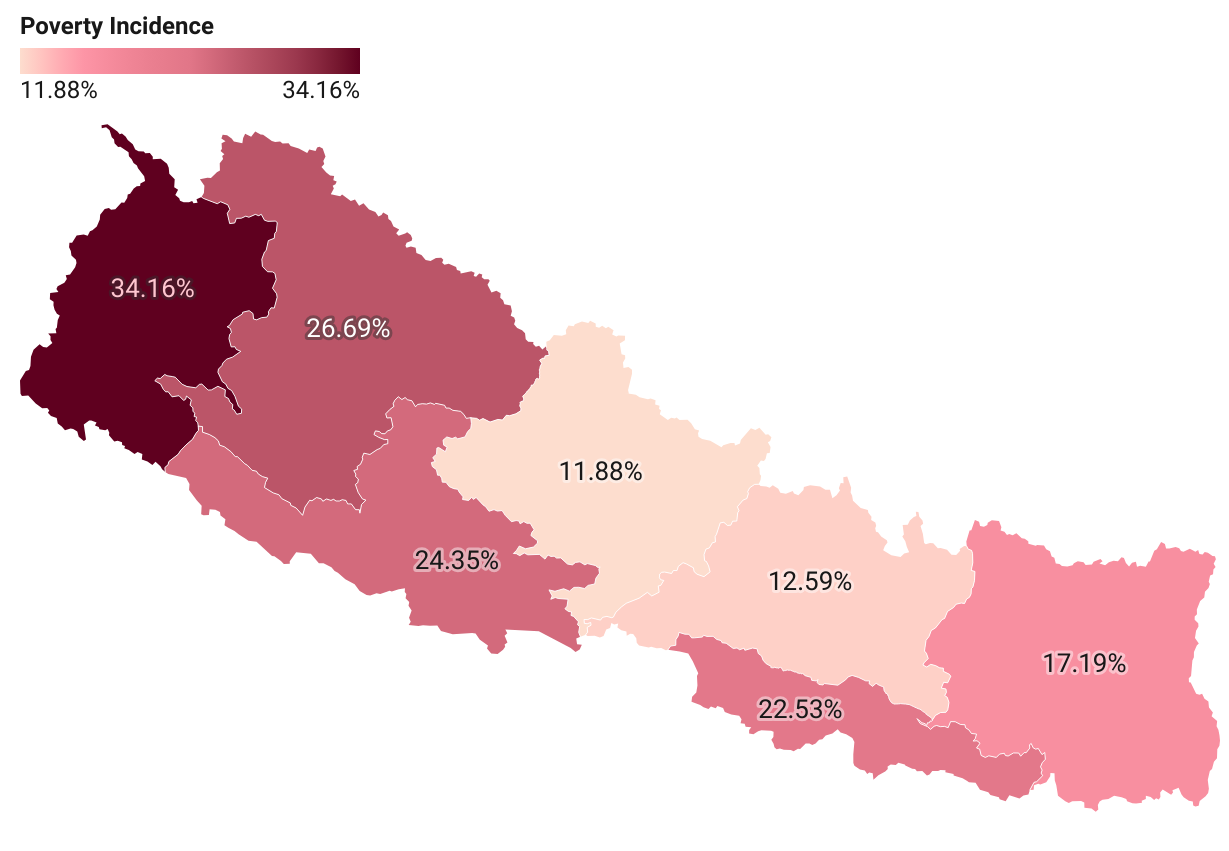

This disparity prevents poorer households from investing in essential services like education and healthcare, trapping them in a cycle of poverty. The poorest 20% spend as much as 67% of their income on food in rural areas of Madhesh province, whereas the richest 20% they spend as little as 28% of their income on food in Kathmandu Valley. Provinces such as Karnali, Sudurpashchim, and others face significant challenges in breaking the poverty cycle due to limited investment in non-food resources. This represents a significant variation in the incidence of poverty across the seven provinces as illustrated in Figure 2, with the poverty rates higher than the national rate in four of the seven provinces. The poverty depth and severity are also higher in provinces with a higher poverty headcount. Having a majority of provinces unable to invest in non-food resources can hinder Nepal’s sustainable and inclusive growth.

Linking the disparity to the broader context of wealth and income inequality, as discussed in the article “Examining the Dynamics of Wealth and Income Inequality in Nepal,” the relationship between poverty and inequality becomes evident. The article explains that wealth and income disparities exacerbate poverty by limiting access to opportunities and resources for the poorer segments of the population. This dynamic further increases inequality, ultimately making it challenging for impoverished households to escape the poverty trap.

Figure 2: Poverty Incidence (headcount) by Province Source: Nepal Living Standards Survey-IV 2022-23, NSO

Source: Nepal Living Standards Survey-IV 2022-23, NSO

The concept of poverty trap

A significant number of people living just above the poverty line are at risk of falling back into poverty due to minor shocks, such as a sudden loss of remittance income or a health crisis. Shocks like the 2015 earthquake, economic blockade from India, and the COVID-19 pandemic have prevented Nepal from reducing its poverty levels to single digits. As of now, remittances play a crucial role in Nepal’s economy. They accounted for 22.82% of the country’s GDP in FY 2022/23 AD, with around 90% of remittances used for daily consumption. This inflow of money has helped reduce poverty by increasing household incomes and consumption levels. However, reliance on remittances is not sustainable in the long term as a sudden loss of remittance might push majority of people back into the poverty line.

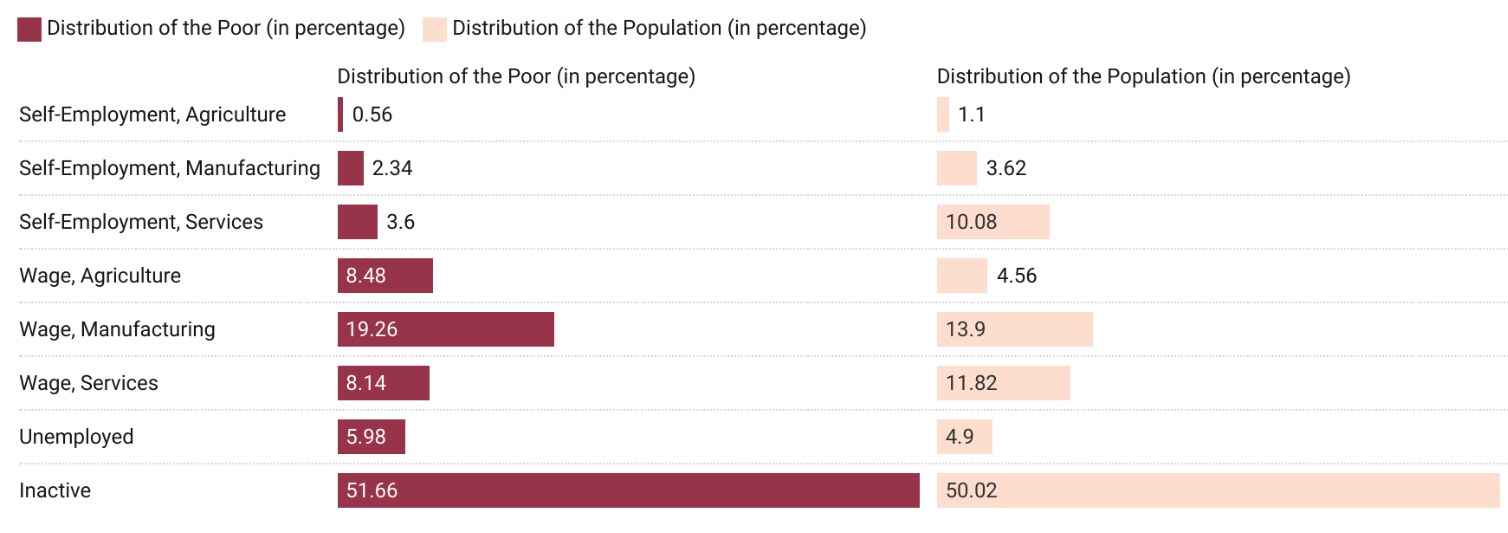

The economic consequences of poverty in a society are profound and extensive. Individuals compelled to depend on inadequate work, like subsistence farming and informal day labor, struggle to achieve economic stability. Conversely, those in households where the head is employed in the services sector are less likely to experience poverty. Poverty headcount rates are highest among households headed by agricultural wage workers (37.81%) and lowest among those with heads who are self-employed in the services sector (7.26%).

Moreover, access to education, healthcare, nutrition, and security disproportionately impacts children and can lead to lifelong issues. People who are born into poverty often lack the opportunities needed to achieve economic stability, making it likely for them to raise another generation of impoverished children. This “poverty trap” perpetuates cycles of inequality, deprivation and marginalization.

Figure 3: Poverty by Occupation of Household Head Source: Nepal Living Standards Survey-IV 2022-23, NSO

Source: Nepal Living Standards Survey-IV 2022-23, NSO

How can Nepal escape poverty?

To break the cycle of poverty, households should be encouraged to invest remittance income in productive sectors like agriculture, small businesses, and health, rather than solely on consumption.

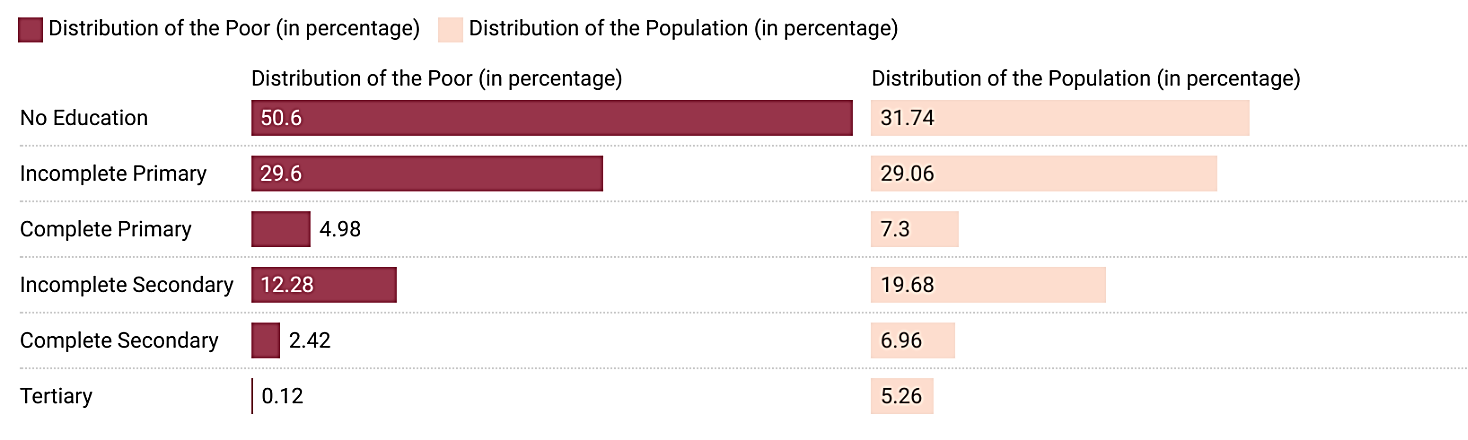

Education is a powerful tool against poverty, with a bidirectional relationship. The NLSS-IV reveals that poverty rates are significantly higher among households where the head of the family lacks education. The poverty rate is 2.5 times higher in such households compared to those where the head has completed at least primary education. Households with heads who have completed tertiary education have a poverty rate of only 0.12%. This stark contrast underscores the importance of education in breaking the cycle of poverty. Policies should prioritize all children, regardless of socio-economic background, having access to quality education as a sustainable way to escape poverty.

Figure 4: Poverty by Education Level of Household Head Source: Nepal Living Standards Survey-IV 2022-23, NSO

Source: Nepal Living Standards Survey-IV 2022-23, NSO

Conclusion

While Nepal has made strides in reducing poverty, significant challenges remain. One-fifth of the population still lives below the poverty line, unable to afford basic needs. The relationship between education, remittances, and poverty highlights the need for comprehensive and sustainable policies. By investing in education, promoting the productive use of remittances, and strengthening social safety nets, Nepal can build a more resilient and inclusive economy. Addressing poverty is not just about increasing income; it is about enhancing people’s capabilities and ensuring that all citizens have the opportunity to lead fulfilling lives.

Mahotsav Pradhan holds a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honors) from the University of Delhi. Prior to joining Nepal Economic Forum as a Research Fellow, he has worked as Foreign Exchange Intern at Nepal Rastra Bank. He has a keen interest in development economics, with a passion for exploring the dynamics of policy analysis and international finance.