National budgets have emerged as an important tool to address climate challenges for government worldwide. Developing countries have stepped up efforts to align budget allocations according to the degree of climate vulnerability they face, channeling funds to high-risk sectors and regions. Nepal is one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world and is predicted to lose 2.2% of its GDP annually due to climate impacts by 2050. Recognizing this vulnerability and the potential of climate budgeting to provide strategic impetus to climate-change interventions, Nepal was the first country in the world to introduce climate budget tagging (CBT) in 2012.

CBT is a fiscal policy tool used to systematically label public expenditures that are relevant to climate change, enabling better integration of climate objectives into budget planning and execution systems. Since Nepal led the way in 2012, over 18 countries have adopted CBT to embed environmental concerns in their budget, monitoring, and audit processes. However, while Nepal has pioneered climate budgeting, it faces nuanced challenges that need resolution in order to fully unlock the benefits CBT holds.

Climate-Budget Allocation in Nepal

Climate-related budget allocation in Nepal is guided by key policies including the National Climate Change Policy 2019 (NCCP), Environment Protection Act 2019, National Policy for Disaster Risk Reduction, and sectoral climate acts that aim to mainstream climate change in public programs. The government undertook a Climate Public Expenditure and Institutional Review in 2011, which assessed the legal, regulatory, and institutional framework for climate budget management, based on which it introduced the Climate Change Budget Code (CBCC) system.

CBCC is an internationally acknowledged system used to identify, measure, and monitor public funds spent on climate programs. Following this, Nepal started tagging climate-related allocations, presenting its first climate-tagged budget in FY 2012/13, allocating 6.7% of the total budget to climate spending. Since then, funding for climate initiatives has increased substantially, rising to 35% of the total budget in FY 2023/24.

Budget allocations to climate programs have seen a particular increase in recent years. Climate budget funding increased from USD 3.2 billion in FY 2017/18 to USD 4.7 billion in FY 2023/24, peaking in FY 2022/23 with a USD 5.2 billion allocation. During this time, climate budget allocations to sub-national governments ballooned, given the government’s strategy which prioritized a decentralized approach to climate action. Local governments saw a 35% increase in climate budget allocation between FY 2018/19 to FY 2020/21.

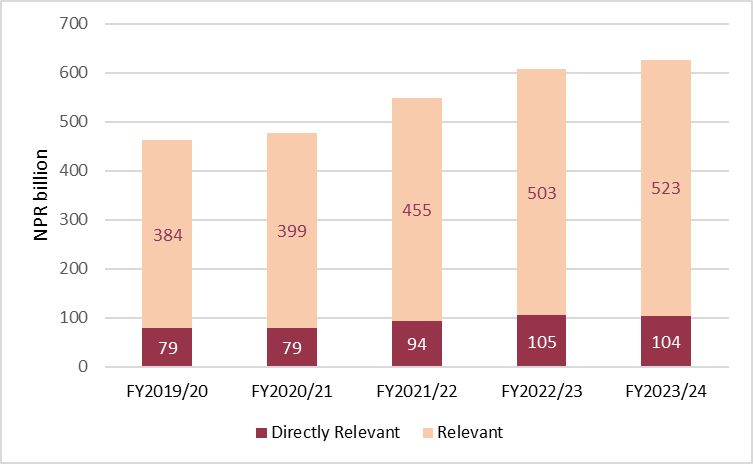

However, despite the large fiscal quantum directed to climate change, the relevancy of the climate budget has seen little improvement over time (Figure 1). In FY 2014/15, 17% of the climate-relevant budget was tagged ‘directly relevant’ while the remaining 83% was tagged ‘relevant’. The directly relevant’ allocation saw no growth over the years (in percentage terms), despite expectations of a stronger fiscal response to climate change. Instead, it marginally declined over the five year period shown in the figure. This is a concerning trend that raises questions over the adequacy of budget funding in attaining the climate goals the country has set out to achieve.

Figure 1: Climate-Relevant Budget Allocation for the Last Five FYs

Source: National Statistics Office

Status of Climate-Budget Expenditure in Nepal

Nepal has been an early adopter of climate budgeting. However, along with the declining relevancy of climate budgeting, federal climate expenditure has also taken a hit over the years. Between FY 2018/19 to FY 2020/21, the average aggregate climate-change spending was 88.4% of the allocated budget, with the lowest expenditure in FY 2019/20 at 85%. The World Bank’s PEFA Assessment grades this expenditure performance as ‘C’, which reflects a weak performance in climate-budget utilization. This is further evident in the ongoing fiscal year’s (FY 2024/25’s) mid-term budget review, where climate change has the lowest budget utilization among the expenditures categorized by the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Such underspending comes at a time when climate-induced floods wreaked havoc in the country just months ago; and this year’s forest fire season has started early, with experts warning that “the worst is yet to come”.

Besides the federal government, the sub-national level plays an important role in climate-change budget management. Provinces and local governments are responsible for disaster risk management and monitoring and evaluation of environment-focused programs implemented under their jurisdiction. Climate change is integrated into the conditional grants they receive from the federal government to carry out the climate functions that fall under their remit. In FY 2020/21, provinces spent NPR 109 billion on climate-related activities while local governments executed projects totaling NPR 297 billion.

Furthermore, to aid decentralized climate action; through the NCCP 2019, the federal government committed to direct 80% of funds mobilized through international climate finance to the local level. Driven by this policy, and coupled with the increased recognition of decentralized climate action, climate funding at the local level increased steadily in recent years, reaching NPR 262 billion in FY 2020/21.

The local level spent 100% of the climate budget allocated to them during FY 2018/19 to FY 2020/21, at times exceeding the budget allocations they received. Similar trends are observed at the provincial level, where climate expenditures have often surpassed original budget allocations. This is a standout phenomenon in the country’s public expenditure landscape, which suffers from considerable underspending.

Challenges in Climate Budgeting

It is important to note Nepal’s commendable achievement in leading climate budget tagging globally, but as this exercise evolves with time, challenges remain. The World Bank has noted that despite important advances in public finance management, measures to support comprehensive climate-responsive expenditure tracking in Nepal are still developing, and the existing systems have not yet been used effectively.

Legislative scrutiny of the budget process is weak as parliamentary committees mainly review revenue and expenditure figures but do not discuss climate-related fiscal risks. Additionally, while the Public Accounts Committee (responsible for reviewing the audit reports submitted by the Office of the Auditor General) has scrutinized climate-relevant expenditures and issued appropriate directives to the government, there is yet to be a mechanism to monitor the progress on the implementation of its decisions.

While the national budget tags expenditures as climate-relevant, it does not flag expenditures that cause an increase in carbon emissions or go against the National Climate Change Policy. The use of Rio Markers (markers that identify if expenditures contribute to improving biodiversity, climate change, or desertification) is missing, whose usage could significantly enhance climate tagging and enable better categorization of climate-spending data.

Additionally, climate expenditure at the provincial level is tracked through a system called PLMBIS, but mechanisms to comprehensively track local-level climate spending are yet to be implemented. Upgradations to the Sub-national Treasury Management System (the IT software used to manage government finances) are expected to improve local climate expenditure tracking, but local governments’ limited technical capacity constrains its full usage.

Furthermore, public procurement, a core pillar of public finance management, does not yet include a specific provision for climate responsiveness. Standard bidding documents do not take into consideration climate-responsive standards in applications to public contracts. Given around 70% of the country’s budget is executed through contracts, it is critical to introduce reforms that integrate climate sensitivity into the bidding and awarding of tenders.

Way Forward

Nepal has made commendable gains in climate-responsive public financial management, but reforms are needed to sustain the momentum of progress. Resource allocations should focus on increasing allotment to the ‘highly relevant’ climate budget category and aim to draw in funding from the ‘neutral’ segment which remains concerningly large. On the expenditure front, while sub-national climate spending remains impressive, measures to comprehensively track the nature (capital/recurrent), type (functional classification disaggregated), and productivity (impact) of expenditures are needed.

Building sub-national capacity and devolving personnel to the staff-starved local governments is required to enhance public finance management outcomes. Additionally, public procurement, which largely remains untouched by climate considerations, should integrate climate change into the eligibility, assessment, and awarding of contracts. Effective climate change management requires economy-wide action, and climate budgeting is a powerful tool to achieve the sustainable development the country has envisioned.

Anurag Gupta is a Research Fellow at the Nepal Economic Forum. He holds a Bachelor's in Economics from Kirori Mal College, University of Delhi. He is passionate about public policy, with a particular interest in public finance, fiscal federalism, and governance.