History of Electrification in Nepal

The expansion of electricity access in Nepal’s rural areas has rapidly increased since the early 2000s, with hydropower leading the way, followed by solar and wind energy. Before the 2000s, less than 35% of the rural population had electricity access. As of 2022, this percentage stands at a whopping 93.7%. All of this began in 1911 when Nepal’s journey in hydroelectric power started with the establishment of a 500kW hydropower plant in Pharping, followed by a second installation in 1934. However, the further development of hydropower was lethargic until the 1960s as it was not a priority for the government. Then, between 1965 and 1975, five government hydropower plants were installed. However, these were primarily benefiting urban areas. A plan for rural areas was made only after the creation of the Small Hydel Development Board (SHDB) in 1975. This government body was responsible to install micro hydropower plants in rural areas, usually at district centers. Unfortunately, as Nepal had little experience with hydroleectrification, the ambitious plans of the SHDB were not successfully completed.

The major pivot in electrification only came after the establishment of the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) in 1985, a governmental body created for the generation, transmission, and distribution of electricity across Nepal. Following NEA’s establishment, by 1989, 21 mini and micro hydropower plants, ranging from 32kW to 345kW were in operation in every region of Nepal. Over time, this has increased manifold as now, as of 2024, the total registered Micro Hydropowers (MHPs) throughout Nepal stands at over 11,300 which benefits almost 35,000 rural households.

Alongside this, the journey of solar and wind energy reflects a blend of early experimentation and resource mapping, albeit with slower progress. The first solar photovoltaic (PV) system of 130 kW was installed in Tatopani, Kodari, Simikot and Gamgadi, with support from the Government of France in 1980s. This mainly benefited remote communities by providing basic electrification in schools, health posts, and communication centres. Parallelly, the first wind turbine of 10kW turbine was installed by the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) in Kagbeni in Mustang district in 1985, which was shortly destroyed by extreme winds. However, due to high upfront costs and limited domestic investment, progress remained slow for both technologies. Upon the establishment of Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC), under the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Environment (MoSTE) in 1996, renewable energy initiatives received structured support. AEPC promoted solar energy through projects such as installing solar mini-grids and rooftop systems, benefiting over 8,306 solar home systems till date. Whereas for the wind-energy, it studied potential sites and implemented small-scale-wind-solar hybrid systems in location like Nawalparasi and Makwanpur.

Policies Influencing Rural Electrification

The policies developed over the years have played a significant role in shaping Nepal’s rural electrification landscape. One of the key legislations includes the Nepal Electricity Act 1992, which exempted small-scale generation up to 1000kW from licencing requirements, thus promoting off-grid electrification through micro-hydro and solar technologies. Meanwhile, the NEA Community Electricity Distribution By-Laws of 2003 initiated community-based grid-connected rural electrification, allowing local entities to manage electricity distribution. This was passed with the aim to reduce non-technical issues such as theft, billing errors, and administrative burden on NEA, adopting a decentralized approach. On the other hand, the Rural Energy Policy (2006) emphasized developing renewable energy technologies and reducing dependence on traditional energy sources. Additionally, the Renewable Energy Subsidy Policy (2000-2022) provided financial incentives for off-grid projects, supporting remote communities. While the subsidies varied across regions due to geographical and economic conditions, it encouraged private sector and community participation in renewable energy development. It ensured that technologies were affordable to low-income households, thereby improving energy access in remote areas. Thus, these policies collectively mandated grid-connected electrification, promoted community participation, and facilitated off-grid solutions across Nepal.

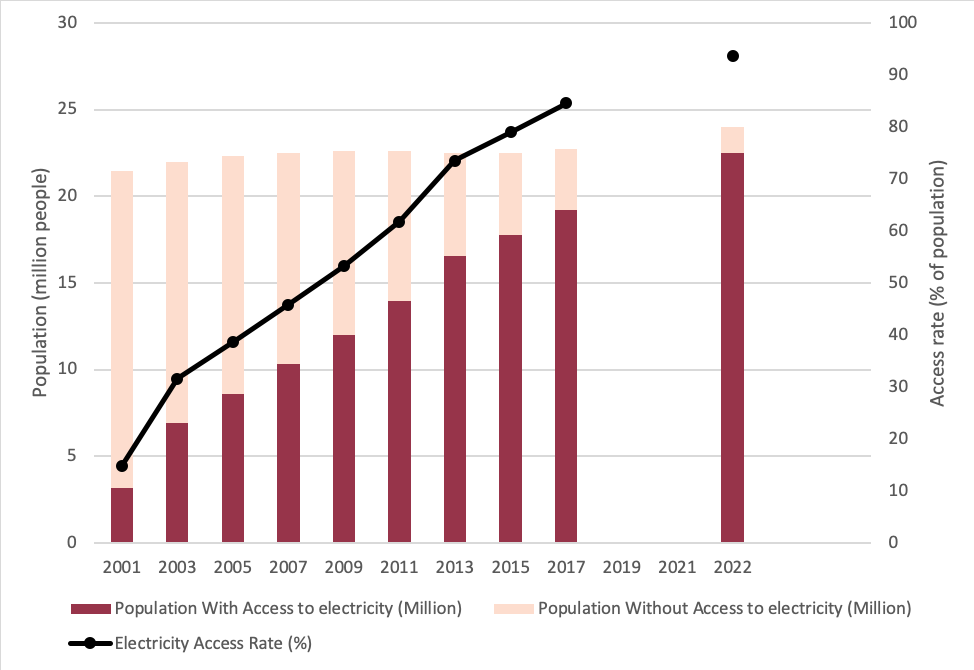

Figure 1. Access to Electricity in Rural Nepal from 2000 to 2022 AD

Source: World Bank. Population estimates based on UN population data

Figure 1 illustrates Nepal’s progress in electricity access from 2001 to 2022 AD. It reflects a significant increment in population with the access to electricity and corresponding decrease in the population without access to electricity. The electricity access rate has steadily risen, reaching almost 100% in 2022.

Benefits Beyond Electricity

Rural electrification in Nepal has catalyzed transformative changes beyond merely providing lights. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), energy access can reduce post-harvest losses by up to 30%. Rural energy development can also significantly support agricultural transformation via irrigation pumps, cold storage, and processing facilities. A notable example is the Solar Power-based Integrated Drinking Water and Agrovoltaic Farming System project in the Lalbandi Municipality in Sarlahi district in 2023, which was facilitated by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and AEPC. The project supported agricultural development by revitalizing abandoned farming lands. Farmers cultivated high-value crops like lemon saplings and explored other agricultural opportunities such as dragon fruit farming underneath the solar panels. It also promoted systems that provided consistent irrigation while facilitating judicious distribution of fertilizers, seeds, and pesticides. Moreover, this project demonstrated how electrification can drive clean cooking adoption along with agricultural transformation. Households that were connected with solar micro-grids used electric induction stoves, reducing fire consumption by around 40-60%.

Electricity access has also played a crucial role in the tourism sector. For instance, a 50kW micro hydropower plant installed in Ghandruk village, under the Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP) in 1990, supplied electricity to 250 households and 20 hotels. Later, ACAP also supported hotels to install solar hot water systems. This allowed hotels to provide better facilities for trekkers, guides, and porters such as better accommodation, communication services, and reliable electricity for lighting and heating. Also, the 600 kW Thame Project in the Everest Region demonstrated the benefits of electricity access for boosting mountain tourism. With electricity access, businesses such as tea shops, restaurants, cyber cafes and bakeries were able to improve service quality with new amenities such as refrigeration and electric cooking appliances. This attracted more customers, thereby allowing local entrepreneur to expand their businesses and revenues.

Additionally, Nepal’s journey from severe load-shedding to improve energy access has made daily life of people easier, especially in rural areas. Before 2017, Nepal faced severe load-shedding issues, with power cuts upto 18 hours a day which disrupted regular activities such as communication, economic activities, and basic services, impacting education as students struggle to study without lighting. Nevertheless, with improvement in energy supply, electrification has not only led to a notable increase in study hours of students, benefiting their education, but also facilitated the installation of mobile towers and internet services. For instance, Gham Power’s solar micro-grids in Khotang, installed in 2015, powered 146 households, 20 institutions and a mobile BTS tower supporting over 10,000 individuals across three villages.

Challenges

Although 93.7% of the rural households have access to electricity from on-grid and off-grid sources, there exists an unequal geographical distribution of electricity access in Nepal. The western part of the country lags behind the rest of the nation in electricity infrastructure. The access to electricity in Karnali and Sudurpaaschim provinces stands at 49.63% and 81.82% respectively, whereas the figures for other provinces exceed 90%. This is mainly due to the inadequate infrastructure and “one-size-fits-all” approach which doesn’t consider the unique needs and priorities of different regions of Nepal. For instance, Karnali regions are characterized by rugged terrain, steep mountains, and isolated communities that are difficult to reach. The high transportation and infrastructure costs combined with challenging location make it uneconomical for grid expansion in such areas. Moreover, existing off-grid technologies are mostly standardized models rather than region-specific planning further delaying effective electrification in these remote regions.

Additionally, a key challenge in expanding electricity access is the limited coordination between AEPC and NEA, given they are housed within different ministries. The AEPC falls under the MoSTE, while the NEA is housed within the Ministry of Energy, Water Resources and Irrigation (MoEWRI). While they both aimed to expand electricity access, their different operational frameworks create challenges in complementing each other’s work. For instance, AEPC might initiate an MHP project to provide the community with an off-grid solution. However, later on, NEA might decide to expand the grid in the same location as AEPC’s project site, making existing MHP redundant. There is difficulty in predicting how the annual grid extension plan of NEA will impact the MHPs project run by the AEPC.

Way Forward

The outlook of rural electrification in Nepal looks promising. The 16th Five-Year- Plan of Nepal emphasized the transition from fossil fuel energy to an increment in the share of renewable energy such as solar, wind and hydrogen. The Commission plans to leverage international climate finance to drive the clean energy transition envisioned in the five-year plan. According to the government’s policies and plans for , Karnali and Sudurpashim will see higher levels of electrification through micro-hydropower, solar and wind energy technology within the FY 2025/26 AD. Moreover, along with domestic targets, international commitments like Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7, under which Nepal has set indicators for affordable and clean energy.

Furthermore, the priority should be given to MHPs for off-grid electrification in Nepal as they are much cheaper than alternatives like diesel and solar for similar service delivery. In order to ensure economic benefits of MHPs, continued subsidy is crucial in rural communities where initial investment cost can be a significant barrier. Further, focus on connecting MHPs to the national grid is essential for optimizing the efficiency of electricity distribution. Overall, with region-specific strategies and rising energy investments, Nepal is on a path to significantly improve the quality of life in rural regions.

Kriti Baral is currently an intern at Nepal Economic Forum and is in her final year of pursuing a Bachelor's in Development Studies at National College. Her keen interest lies in energy management and storytelling, where she seeks to merge analytical thinking with creative communication to drive meaningful impact.