In June 1930, the United States introduced the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, a piece of legislation originally only intended to raise import duties to protect American farmers who were struggling to compete with agricultural imports from Europe. However, when the act was introduced, lawmakers demanded similar protection for their own industries and by the time the bill passed, it was calling for increased tariffs on 890 different items. The result was devastating. Affected countries retaliated with tariffs of their own, triggering a wave of protectionism that severely disrupted international trade trade which consequently inflamed the Great Depression. Today, history appears to be repeating itself, as the U.S. once again turns to tariff policies amid rising global economic tensions.

Why Introduce Tariffs Despite the Costs?

A tariff, on its own, is neither inherently good nor bad. It is a widely practiced policy instrument used to tax imported goods. In essence, tariffs are designed to encourage the consumption of local goods and protect industries from foreign competition. As foreign goods are relatively more expensive after tariffs, this drives up demand for domestic products. When used correctly, tariffs can increase the production and tax revenue as well as correct trade imbalances. For example, Nepal charges 5% tariff on ginger, 10% on fresh apple, and 40% on coffee and tea in an effort to encourage local production.

This is also the basic rationale presented by current American President Donald Trump for the ongoing proposition of trade policies. The primary goal of the tariff structure introduced by the Trump administration is to reduce dependency, and de-risk and decouple key sectors including advanced semiconductors, pharmaceutical and medical supplies, steel, and aluminum. However, if we look at the other side of the tariff, as goods become relatively more expensive in the importing country, demand falls and thus leads to a lost market share and lower GDP. Therefore, tariffs are used to apply pressure on the foreign government they are imposed on, as part of a trade negotiation or a political tool. The Trump administration has also justified tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China as a way of pressuring them into addressing problems of illegal immigration and drug trafficking, while also aiming to reduce the trade deficit of the United States.

Timeline of Trump’s Tariffs

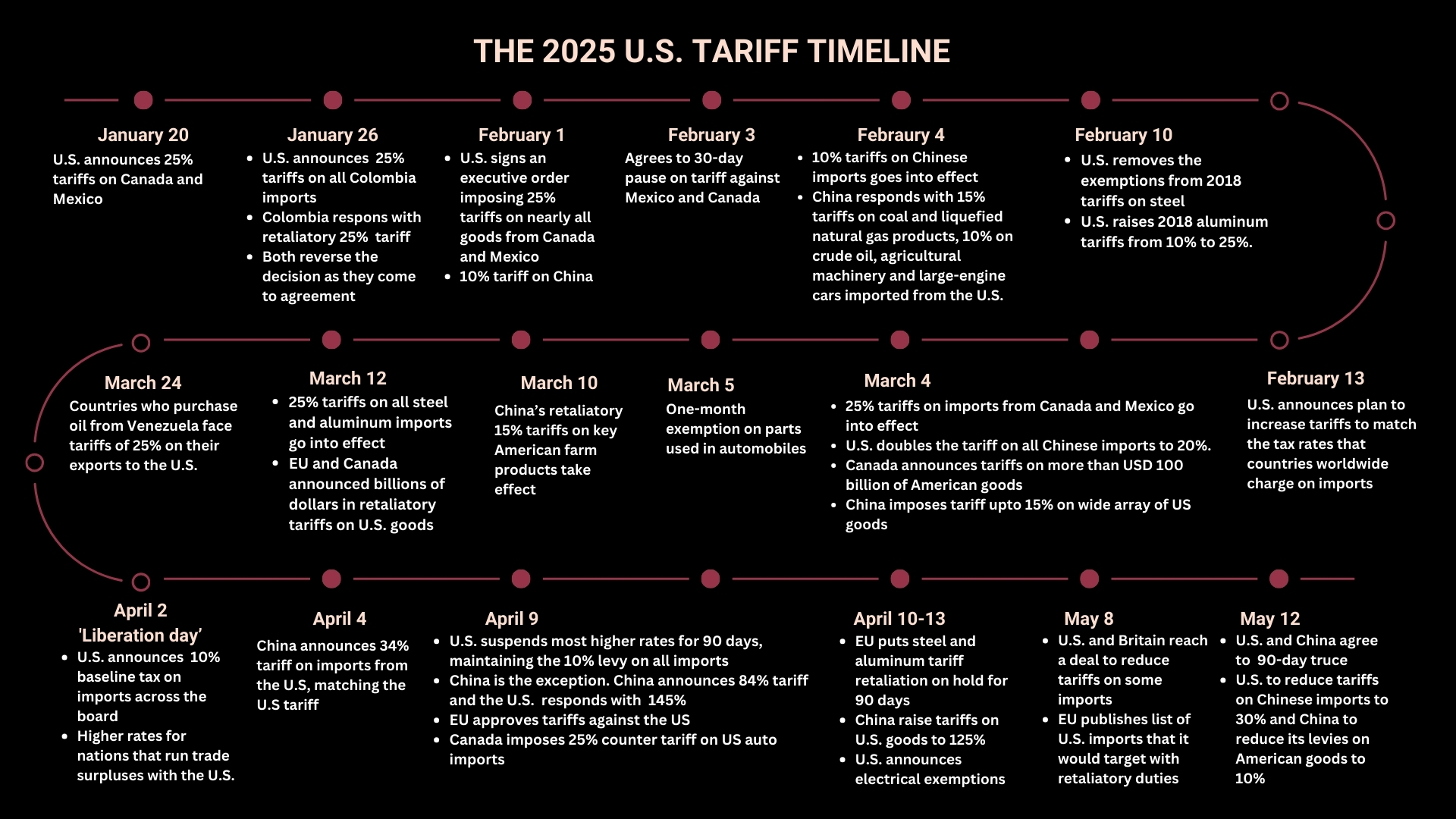

In accordance with the objective outlined above, one of the major steps that President Trump took as he came into power was to immediately introduce tariffs as promised in his election campaign. Since then, the U.S. tariff regime has undergone many revisions alongside the retaliation from affected countries including Canada, Mexico, China and the European Union. Tensions peaked on April 2, 2025 when President Trump announced a 10% baseline tariff on imports across the board, with higher rates imposed on specific countries: 34% on imports from China, 20% from the European Union, 25% from South Korea and 24% from Japan. This day was later declared as ‘Liberation Day’. In recent update, the United States has retracted the previously announced tariffs and declared a 90-day truce following successful bilateral negotiations. While this marks a temporary de-escalation, the long-term trade landscape still remains uncertain.

For a detailed breakdown, Figure 1 displays a timeline outlining the major developments.

Figure 1. Timeline of Tariff Rates Proposed by the U.S.

Source: New York Times

The Impact of the Tariffs

The volatile tariff rollout triggered a global economic shock, severely disrupted supply chains, and led to stock market mayhem, with sharp declines in investor confidence. At the same time, the GEP Global Supply Chain Volatility Index, a monthly survey of 27,000 businesses tracking the demand conditions, shortages, transportation costs, inventories, and backlogs, reported a decline in purchasing activity of manufacturers in April 2025, specifically in North America, and to a lesser extent in Asia. The steep fall signaled a probable production slowdown as manufacturers scaled back in anticipation of reduced future demand as a direct result of the tariffs.

Many domestic industries rely on imported inputs within their global supply chains. Rising import costs have increased production expenses for these firms. If producers pass these costs on to consumers, prices of domestically manufactured goods will also rise. This would leave the burden of the tariff on normal citizens who would have to pay a higher price for the same product. Thus, the tariff has become a regressive tax in the sense that consumers who have lower incomes have to pay a larger portion of their incomes for the same product.

A report by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs depicts a similar bleak picture. Global GDP growth projection is down to 2.4% in early-2025, 0.4 percentage points below the January 2025 projection. Furthermore, trade growth is projected to halve from 3.3% in 2024 to 1.6% in 2025. This drastic falloff is uniform to both developing and developed countries. Meanwhile, the U.S. economy is projected to slow from 2.8% growth in 2024 to 1.6% in 2025, while China’s growth is expected to slow to 4.6%. Other major emerging economies, such as Brazil, Mexico, and South Africa, are also facing economic downturns due to declining trade and reduced investment. Furthermore, inflation rates have surpassed pre-pandemic levels in nearly two-thirds of countries, with over 20 developing economies experiencing double-digit inflation.

Nepal, on the other hand, has not been directly targeted by the current wave of tariffs. It remains subject to a 10% base tariff on exports to the United States. However, most Nepali products benefit from duty-free access to the U.S. under the Nepal Trade Preference Program (NTPP), which covers 77 tariff lines, including select travel goods, apparel, made-up textiles, and headwear. Nevertheless, as with all countries, Nepal faces indirect repercussions from the global trade disruptions and tariff-induced shocks.

Current Outlook

The policy shift has reshaped trade flows. A survey conducted by trade insurer Allianz Trade found that, from a poll surveying 4,500 exporters across several major economies, 95% of Chinese exporters are planning to diversify away from America. In parallel, U.S. firms are looking to shift the production out of China. This move appears to have benefited Europe as firms are expanding to Europe. Previously underutilized supply chain capacities in countries like Germany and France are now showing signs of growth as spare capacity, which measures the gap between actual output and potential output, shrinks further. Besides Europe, Southeast Asia is also emerging as a potential market. A study from China reported that local businesses favor Indonesia as the top destination to move production overseas.

The U.S. has moved the wheel. The market is adjusting, and change is in motion. We have yet to see whether this will go down as a historic downturn or if there will be a rise of a new global order. However, it is certain that the international market will go through massive restructuring, and this holds both risks and opportunities. The outcome of this shift depends entirely on how each country chooses to respond and for Nepal, this is a critical opportunity. By leveraging the gaps in the global supply chain, Nepal could position itself as an emerging market player. The path forward will be shaped by the decision we make in this pivotal moment.

Heykha Rai holds a Bachelor’s in Economics from Kathmandu University and serves as a Research Fellow at the Nepal Economic Forum. With a keen interest in international economics and economic history, she contributes insightful research to advance economic discourse. Passionate about policy analysis and development strategies, Heykha is dedicated to fostering informed economic decision-making in Nepal.