Context

Without its migrant workers, where would Nepal be? Since the 1990s, increasingly many Nepalis are moving out of the country in pursuit of foreign employment to send money back home. Nepal has reached a critical juncture that calls for introspecting whether Nepal would have been better off or worse off had its migrant workers stayed back. While imagining such kind of counterfactual scenarios requires subjective judgment, realizing the substantial impact of migrant workers’ remittances on the Nepali economy is evident from both household and national levels. This article analyzes how emigration and remittances are evolving in Nepal with respect to key trends, driving factors, and their impact on the Nepali economy.

Voting by feet to make ends meet

Emigration is a household story in Nepal. At the global level, 2020 oversaw 3.6% of the world’s population living as international migrants. While staying back in birth country is the prevailing norm for the vast majority, Nepalis seem twice as likely than the global population to migrate abroad. From a population size of over 29 million, 7.5% of Nepal’s population is reported to be living abroad in 2021 according to National Population and Housing Census 2021. Out of 2.1 million absentees, 82.2% are males and 17.8% are females. The household level data – 23.4% of 6.6 million total households – shows that nearly one in every four households in Nepal has a family member living abroad.

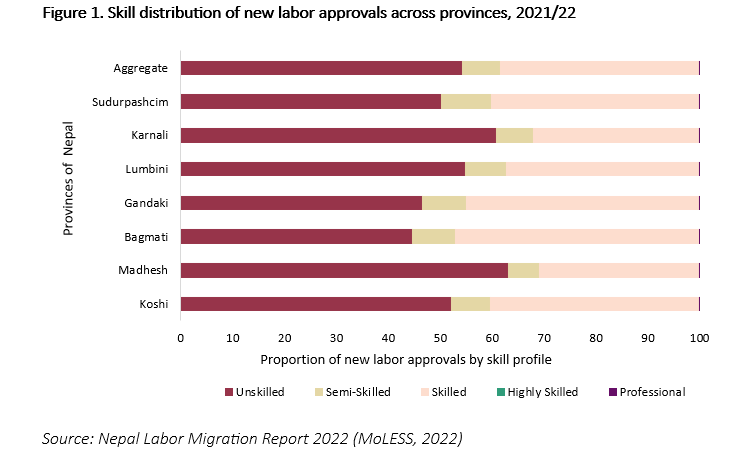

Geography moulds international migration from Nepal. Labor approvals issued from 2019 to 2022 paints an uneven pattern of overseas migration from the provinces: Madhesh (28.7%), Koshi (20.2%), Lumbini (16.8%), Bagmati (15.5%), Gandaki (12.2%), Karnali (3.8%), and Sudurpaschim (2.7%) Karnali’s and Sudupaschim’s seemingly low emigration rates belies their tendency to migrate via open-border Nepal-India corridor that goes grossly undocumented. Based on their human capital composition, Nepali migrants gravitate towards primarily three regions, namely India, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) as well as Malaysia, and the advanced countries. Figure 1 illustrates the labor approvals to be skewed towards lower-skilled roles, predominantly filled by men in security, construction, and contracts, and women in household and caregiving. However, these figures overlook 400,000+ Nepali students who secured No-Objection Certificates (NOCs) from 2008 to 2021 to pursue education abroad, often with the intention of permanent settlement and assimilation into skilled labor pool.

Nepali migrants vote by feet for better prospects. Net migration rates, a form of voting by feet, reflect public perceptions of economic development beyond traditional metrics like GDP per capita or HDI. Nepal’s consistently negative net migration rate indicates more individuals are departing the country because they see better opportunities and well-being in other countries. Moreover, Nepal’s stagnant labor force participation, hovering around 42% since 1990, indicates insufficient job creation. Emigration from Nepal is multicausal yet hope for a better life pulls large share of migrant aspirants to venture abroad.

Giving back to escape poverty and poverty

Remittances account for over one-fifth of Nepal’s national income. Remittances as a ratio of GDP stood at 22% for Nepal in 2022 making it the world’s tenth largest recipient after Tonga (50%), Lebanon (38%), Somoa (34%), Tajikistan (32%), Kyrgyzstan (31%), Gambia (28%), Honduras (27%), El Salvador (24%), and Haiti (22%) . Such a high remittances-to-GDP ratio not only reflects Nepal’s position among fragile countries but also cautions against heavy reliance on international remittances. Moreover, these reported figures underestimates the actual magnitude as informal channels such as “hundi” and Nepal-India migration corridor remain unaccounted for

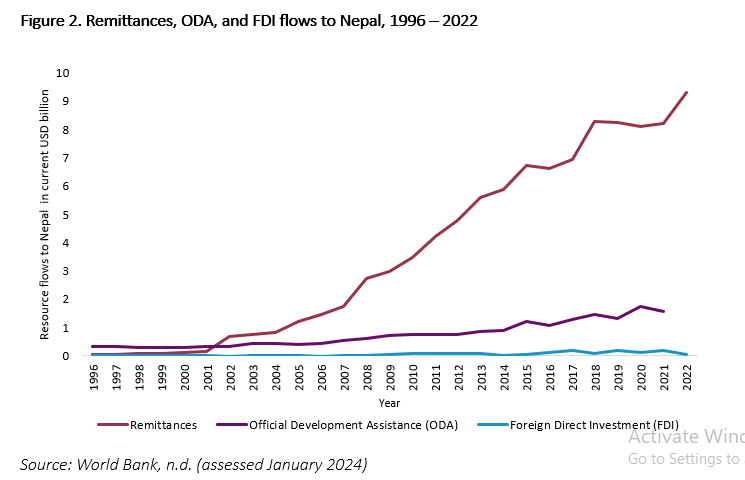

Remittances ease foreign exchange constraints in Nepal. Figure 2 reveals several notable trends in resource flows to Nepal from 1996 to 2022. First, remittances to Nepal surpass the combined inflow of Official Development Assistance (ODA) and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), deviating from the global trend where FDI typically leads resource flows to low and middle-income countries. Second, remittances to Nepal seem to be rising at an increasing rate from 2004 onward. Third, remittances are countercyclical and exhibit resilience during crises, such as Maoist Insurgency, Nepal Earthquake 2015, and the COVID-19 pandemic. These observations underscore Nepal’s need to attract FDI, create jobs, and integrate into the global value chain.

Remittances have lifted Nepali households out of poverty. Nepal’s poverty rate has drastically reduced from 42% in 1995 to 25% in 2010 as per Nepal Living Standards Survey III (NLSS3) Moreover, NLSS3 shows remittances boost household disposable income, which is then mainly spent on consumption (78.9%) followed by loan repayment (7.1%), household property (4.1%), education (3.5%), capital formation (2.4%) and other areas. Several studies based on NLSS3 data have quantified the impact of remittances on poverty alleviation in Nepal. For instance, a 10% increase in remittance inflows reduced the probability of Nepali households entering poverty by 1.1%. Remittances lowered the poverty ratio by 5.3% but widened the gap between recipients and non-recipients, causing an increase in poverty depth by 7.37% and severity by 9.25% .

Looking ahead with a 360-vision

Reexamining Nepal’s development via emigration and remittances guides informed decision-making. While technology has helped bridge the distance, millions of Nepali migrants incur great risks and costs in search of better outcomes abroad. From reducing poverty to easing foreign exchange constraints, Nepal’s migratory wave and remittance inflow are supporting households and the national economy to stay afloat. Amid political turmoil, jobless growth, and unfavorable investment environment, remittances act as a safety valve for Nepali households. Yet, becoming overly reliant on remittances raises the concern posed by their withering away. Along with safeguarding orderly migration for aspirant migrants, engagement platform for the diaspora, and reintegration of returnees, Nepal needs to create gainful employment opportunities within the country for those who want to stay.

Chandani Thapa works as the Coordinator at Nepal Economic Forum and beed at beed management. She holds Master's in Economics (with specialization in World Economy) from Jawaharlal Nehru University and B.A. (Honours) in Economics (with a minor in Mathematics) from Delhi University. Applying the toolkit of economists, Chandani strives to create a positive impact while advancing her capabilities in research, academia, and policymaking.