Over the decades, top-down efforts have been unable to bring about significant results in poverty reduction. Its centralized approach to development has gathered criticism for being ineffective and limited in scope. This has encouraged new vocabulary in the development sphere in the form of bottom-up development, focusing on enriching the process with local community participation. However, a common concern raised about the popular implementation of the ‘community-based approach’ is its tendency to overlook the role of local social power structures, reducing poverty to be an issue of individual capacity. Many efforts fail to properly account for difficulty in accessing social and economic opportunities. Such flawed implementation has, in cases, undermined the priorities of marginalized groups and reproduced the very social inequalities development seeks to eradicate.

Women in Rural Nepal

As of 2024, Nepal is the second-poorest country in South Asia with a GDP per capita of USD 5,032, with 20.27% of the population living below the poverty line. It is significantly higher in rural areas, where the poverty rate is just over a quarter of the population. Traditionally, rural livelihoods depended largely on subsistence farming. In recent years, there has been an increasing trend in off-farm employment, particularly towards migration to urban areas and foreign destinations. With a majority of the migrants being male, there are certain implications on social structures and development. For instance, with a decrease in the number of working-age men in communities, the women often take on more ‘male labor activities’ in conjunction to the burden of domestic work. In the absence of men, women in rural communities have shown increased community participation, contributing to resource user groups such as those for water and community forests.

However, it cannot be said if male out-migration automatically benefits the women who stay behind, with some studies showing positive impact being conditional on the size of the remittance received. Larger remittances allowed for reduced work burdens and increased decision-making roles whereas low remittances were liked to having a larger workload and higher stress. In a similar vein, while some women take on more managerial roles and deepen their economic engagements, it is unsure if this empowerment is sustainable. Major decisions are still made by men, even if they are not home, and they tend to resume the role of the patriarchs upon returning.

Limited Financial Autonomy

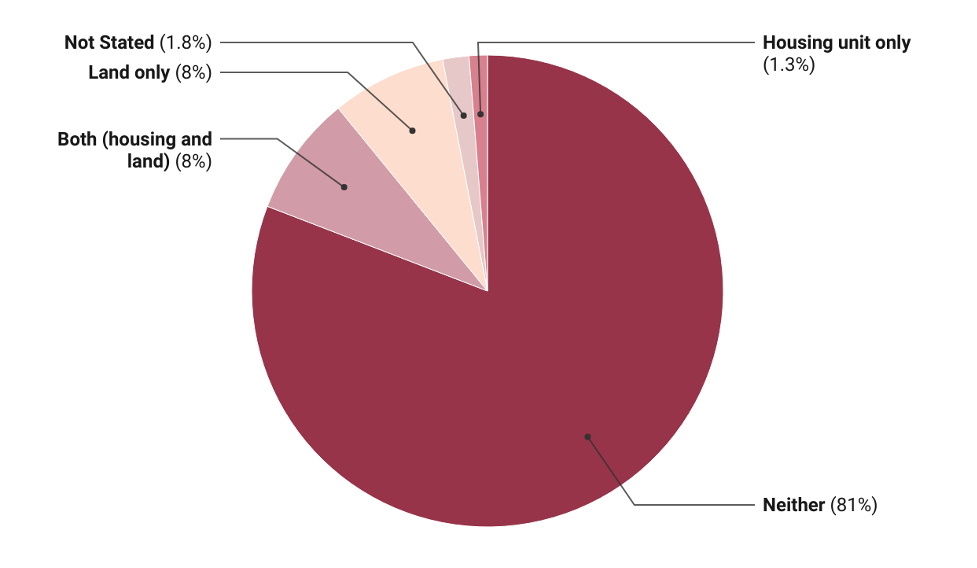

When it comes down to financial security, women are more vulnerable than their male counterparts. For starters, there is a significant disparity in asset ownership. Land and houses are critical assets to enhance socio-economic status. As of 2021, of the 2.1 million households in rural Nepal, only 379,524 had female ownership over the fixed assets – roughly 17%. The lowest was in Sudurpaschim province, with only 6% of households having female ownership. It is, however, progress compared to previous periods, which can be attributed to legal reforms and incentives such as lower land registration fees for women. Nevertheless, the gigantic gap in asset ownership continues to put rural women in the legally vulnerable position of not having control over productive resources.

Figure 1. Households in Rural Nepal with Female Ownership of Fixed Assets

Source: Nepal Population and Housing Census 2021

The limitation brought on by the lack of asset ownership is exacerbated by financial exclusion, limiting women’s access to credit and financial services. Women hold 687 banking accounts per 1,000 population, which is less than half the number held by men at 1,314 accounts per 1,000 population. Similar to asset ownership, the situation is worse for rural women where the number drops down to 201 accounts per 1,000 population, the lowest among all groups across the country. This effectively restricts their access to formal financial services and resources, increasing their dependence on male family members or informal credit sources that charge high interest rates. Perhaps an accurate reflection of this would be how 90% of female-owned companies depend on informal sources to meet financing needs despite multiple government initiatives, including collateral-free loans and concessional credit.

Barriers to Women’s Financial Empowerment

According to National Statistics Office, 29% of enterprises in Nepal are female-owned. However, simply relying on registration is not a strong indicator of women entrepreneurship development. Many businesses are falsely registered under the name of a woman to benefit from government and development initiatives, and they tend to be managed and run by male family members. Women hold very little, if any, managerial rights in these businesses. This dynamic is something that credit facilities targeting women-entrepreneurs have failed to capture so far, and it is also something that is very challenging to do. It is a multi-layered issue that involves social structures, behaviors, literacy rates, and access to finance, among other factors.

Simply announcing benefits aiming to empower women financially does not translate into the targeted women being able to access them. When planning for women empowerment, it is important to consider how limited access to financial resources and assets limits their risk-taking abilities. It is also equally important to consider the challenges associated with moving against the status-quo of patriarchal norms for women who are already financially restrained in this way. Rural women, on average, have lower literacy rates and technical trainings. This aggravates their exclusion from major decisions and their dependence on family members, despite the out-migration of male members. While they may take on certain managerial roles previously reserved for men, they are still held to the traditional standard of being primary caregiver. When trying to empower women entrepreneurially, it is crucial to view how such constraints affect their ability to actively own, manage, and scale-up a business. It also provides insights on the many women entrepreneurs that operate in informal spaces, given the lack of efficient formal support as well as a social structure that limits their entrepreneurial choices and access to household resources.

Impact on Development

When one discusses the significance of women having an equitable share in household assets, it should be underlined that it goes beyond simple economic benefits. It has far-reaching consequences into their security, social, and legal status, many of which trickle down into their families. Women’s economic participation is considered to catalyze development in family health, education, as well as human capital investment. The income generated from their economic activities are invested into household consumption as compared to business expansion. On the one hand, this makes women’s entrepreneurial activities an important factor for the economic well-being of the family. On the other, it can be taken as a reflection of how deeply women are embedded into domestic relationships, where their efforts are seen more as a public good. When a structure excludes women from financial systems, it risks slowing down economic growth in vulnerable rural areas by limiting the productive potential of at least half of the population.

Sukeerti Shrestha holds a Bachelor's degree in Business Administration (Finance) from Kathmandu University. She is passionate about development economics and sustainability, with a keen interest in community-inclusive policy making. Currently, she works as an Aspiring beed at beed Management, building on her prior experience in management consulting and social enterprises.