Waste Management Crisis in Nepal

Waste management has become a significant environmental concern in Nepal over recent years. Rapid urbanization and a shift in consumption behavior means that Kathmandu Valley alone generates 1,200 metric tonnes of solid waste daily, with only a small fraction of this being recycled. Solid waste in Nepal is collected by various methods, including door-to-door collection, collection through community bins, roadside pick-up, and self-delivery. Although these methods provide basic waste collection, they fall short compared to the higher collection rates and efficiency seen in developed countries. For instance, most of the waste produced by Kathmandu Valley gets dumped in the Banchare Danda landfill site, located 2 kilometers from the previous Sisdol landfill site, which had been in operation for 20 years until it became overfilled. In contrast to sanitary landfills in developed countries, Nepal’s open dumps lack adequate standards to prevent environmental contamination. When Balen Shah was elected as Kathmandu’s mayor in 2022, environmental advocates were hopeful that his leadership would transform the city’s waste management. Promising to prioritize Kathmandu’s waste issues by introducing strict laws for household waste segregation and pledging to support the residents of Sisdol, he echoed the commitments made by previous leaders who also recognized the urgent need for change.

Solid waste management (SWM) lies near the bottom of the priority list for many Nepali municipalities, as there is a greater demand to prioritize other public services. Although household-level segregation has improved, its impact is diminished as most waste still ends up being burned, in open dumps, or in landfills, having detrimental effects on Nepal’s ecosystems. A limited focus on these issues has resulted in inconsistent waste management practices across Kathmandu and Nepal as a whole. Even when segregation is attempted, an absence of coordinated recycling efforts makes it ineffective. This complicated relationship between the segregation initiatives and actual recycling processes highlights gaps in the system, making solid waste management in Nepal complex and unaccountable.

Drawbacks of the Linear economy

Before plastic was introduced and consumerism became more common, Nepal’s traditional society naturally embodied many principles of the circular economy. Waste was minimal, and practices like resource efficiency, reuse, and recycling were ingrained as both economic necessities and social norms. For example, organic waste, such as food, was routinely composted or used as natural fertilizer, demonstrating a sustainable approach long before the concept of a circular economy became a formalized theory. But this has stopped being the norm in recent years. A report conducted by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in 2013 found that in rural settings households still practice composting, but those in urban settings where there is limited access to land are generally not able to use this technique. As a result, alternative methods like the production of bio-briquettes have emerged, offering a way to repurpose organic waste into energy. Bio-briquettes not only reduce waste but also provide a renewable energy source, it is resourcefulness like this that will ease the shift to a circular economy.

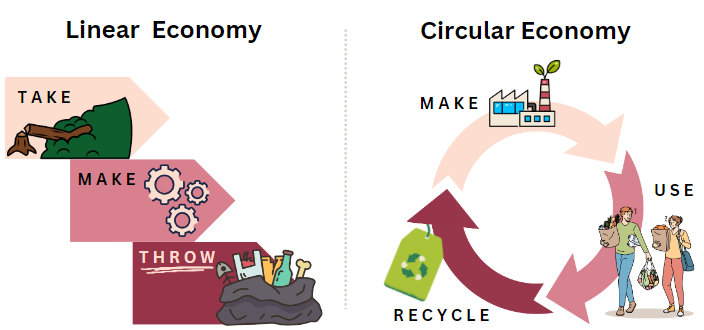

Today, Nepal’s economy is on an upward trajectory, expected to graduate from being a Least Developed Country to a Developing Country in 2026. It marks a fundamental step in the country’s socioeconomic progress. While this is a significant step in the right direction, progress has largely been driven by a linear economy (‘take, make, waste’), which is favored for its convenience and cost-effectiveness, particularly in developing countries where it aligns with existing infrastructure and economic priorities. However, over recent years the drawbacks of the linear economy have become more understood, particularly its significant environmental harm. Nepal’s precarious position as a Himalayan nation, ranked the fourth most climate-vulnerable country in the world, makes the need for a change away from the linear economy even more critical. Especially when climate related disasters have become more common. The number of people in Nepal annually affected by river flooding has been projected to increase to around 350,000 in 2030 from 157,000 in 2010. The nature of the linear economy which encourages constant generation of waste is also a system which depletes natural resources. Reverting to some more traditional practices embedded in Nepali culture will be important in slowing the waste crisis.

Figure 1: Comparison of the Linear and Circular economy

Economic Development and Transitioning to a Circular Economy

If Nepal is to positively embrace the circular economy, where extracted resources remain in use for as long as possible, the country will need to overcome several substantial challenges. Some of these challenges include inadequate infrastructure, insufficient financial investment in the sector and a lack of demand from consumers for sustainable products. Nevertheless, it’s promising to see that despite these barriers, there is slowly a rising consciousness in Nepal of the values of the circular economy. Some municipalities outside of Bagmati province have done a commendable job of managing and minimizing their waste and can be referred to as cases for best practices. An instance is the Waling municipality of Syangja which has demonstrated that, community involvement and inter-body coordination are effective tools for waste management. The municipality has not only efficiently managed its waste but has also enabled the community to generate income through proper waste organization. A solid waste recycling center has been established where waste is meticulously segregated, degradable waste is converted into compost, while non-degradable waste is further segregated and sold for reuse.

Collaboration and cooperation between public and private bodies will too be important in the transition to the circular economy. Leveraging shared resources, expertise, and innovation will help in creating more efficient, sustainable waste management and recycling systems. For instance, the ‘Doko Recyclers’ a social enterprise offering solutions for waste. They have collected over 14 million kilograms of waste since it was founded. The organization is supported by the government and has more than 100 other partners to encourage better implementation of existing policies. Though still in its early stages, these initiatives lay a foundation for future progress toward waste management models for whole communities.

Concluding remarks

While Nepal made an early commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals, waste generation in Nepal is expected to increase in the coming years. A continuation of the status quo where a linear economy dominates will keep up the significant challenges to the current waste management systems. To address this, the government must develop more effective waste-handling procedures and embrace institutional mechanisms to manage solid waste in an effective way. The circular economy is not only about managing waste, but it also encourages responsible planning and design where systems are established to extend a product’s life cycle. In Nepal it will be important to foster a positive perception towards the circular economy, that not only considers immediate concerns but also long-term environmental sustainability. Cooperation among government agencies, private organizations, and the public will be fundamental in achieving these goals.

Charlie Scotchbrook holds a Bachelor’s degree in International Development & Geography from the University of Sussex, UK. Prior to joining Nepal Economic Forum, he worked as an Intern at the Ellen Macarthur Foundation and Redress Hong Kong. He has a keen interest in sustainable development policy, with a passion for the circular economy.