Mobilising Student Exchanges in South Asia

If you’re asked to think of the world’s great universities, you would probably first think of the Ivy League, Oxbridge or other elite institutions in the West. But more than a thousand years before the first students opened their books at Harvard, and 500 years before scholars even began teaching at Oxford, Nalanda Mahavira in modern-day India was already a well-established hub of learning.

At Nalanda, Buddhist scholars taught philosophy, mathematics, medicine and astronomy. The library alone was said to have contained more than nine million manuscripts. But the most remarkable thing about Nalanda was its internationalism. It was the world’s first residential university, bringing together as many as 10,000 scholars from all over South Asia and even beyond, including Tibet, China, Japan, Korea, and Indonesia. Unfortunately, the university was destroyed in the late 12th century by Bakhityar Khilji, a Turkish invader. After the demise of the university, South Asia lost its intra-regional academic hub and never recovered the fluid flow of exchanges.

Today, only a small fraction of South Asian students study in a neighbouring country. To rebuild the tradition of shared scholarly exchanges and academic ties, the region needs a modern educational mobility scheme that enables South Asian students to learn about each other’s countries, form lasting connections and cultivate mutual understanding.

From Intra-Regional Connections to Global Outflows

South Asia was once a region defined by shared cultures, religions, trade routes, philosophies and flourishing academic and cultural exchanges. Ancient centres like Nalanda and Taxila drew students from across the region and, during the colonial era, cities like Lahore and Calcutta were vibrant hubs for literary and intellectual circles. In the twentieth century, young people would visit and explore other countries in the region, fostering grassroot connections between individuals. At the elite level, too, many leaders from across the region spent their formative years in each other’s countries. For example, prominent leaders from countries such as Nepal, Myanmar, Afghanistan, Bhutan and Bangladesh studied in India in the twentieth century.

Until relatively recently, India was the destination of choice for most students from the region, but the advent of globalisation increased the options on offer. Today, South Asian students overwhelmingly tend to seek education in Western countries.

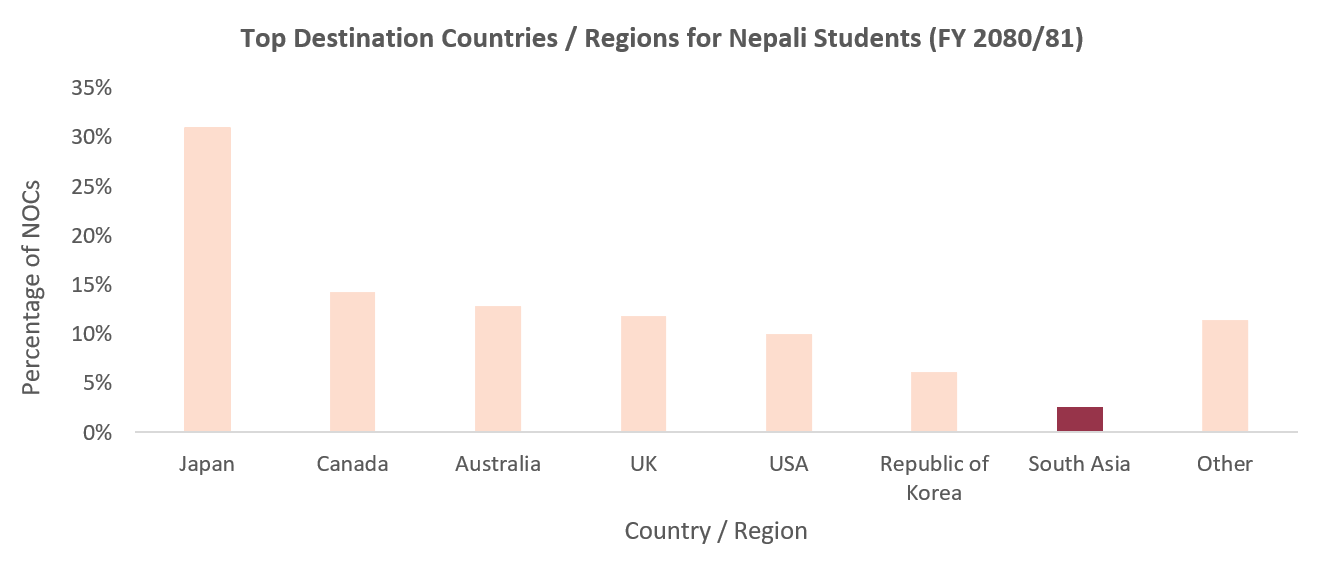

In FY 2023/24 AD (2081/82 BS), the Nepali Ministry of Education, Science and Technology issued 112,256 No Objection Certificates (NOCs), a document required for students to study abroad. Among these students, most went to Japan, Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States and South Korea. Only 2.54% of students went to South Asia, primarily to India and Bangladesh — though it should be noted that many Nepali students study in India without taking a NOC.

Figure 1. Nepal’s NOC certificate approvals by destination country

Source: Ministry of Education, Science and Technology

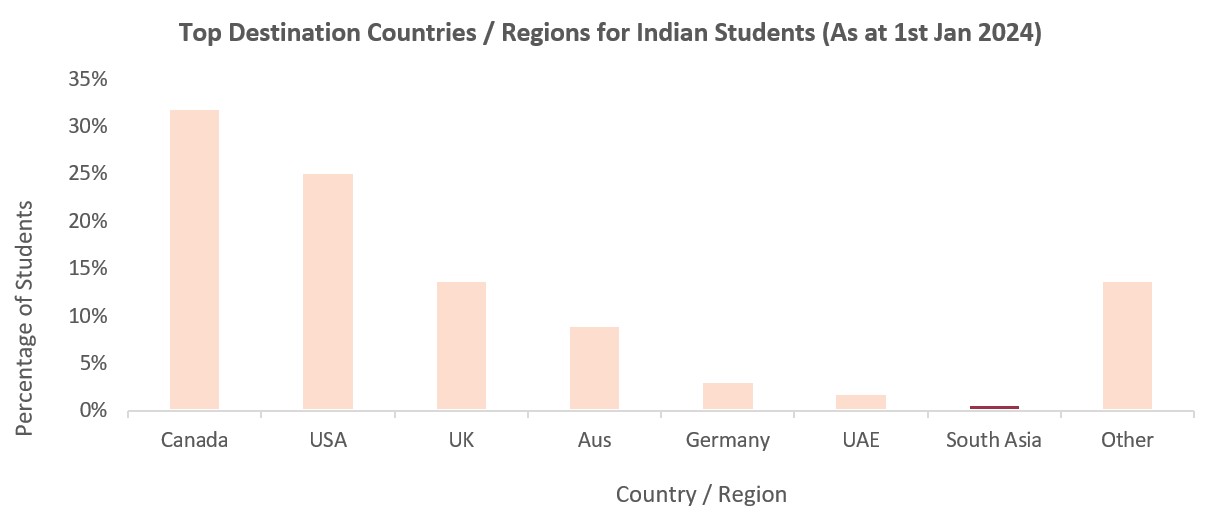

Similarly, most Indian students pursuing higher education abroad are in countries like Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and Germany. Only 0.81% of Indian students are studying in South Asia.

Figure 2. Indian students pursuing overseas higher education by destination country

Source: Ministry of External Affairs

Reports on the top destinations for other South Asian countries suggest similar trends. For Bangladeshi students, the top destinations are the United Arab Emirates, the United States, Malaysia, Australia and Canada. For Pakistanis, the top destinations are the United Kingdom, China, the United Arab Emirates, Australia, and the United States. Finally, for Sri Lankans, it is Australia, Japan, the United States, Malaysia and the United Kingdom.

Putting Education on the Regional Agenda

South Asia’s historical connections have been superseded by narrow national outlooks, border disputes, and political mistrust. The far-reaching implications of these divisions are well-known. The lack of economic integration has led to missed opportunities in trade and development, meaning that South Asia lags far behind its peers in the rest of Asia. Further, political instability and conflicts have hamstrung cooperation, leading to missed opportunities in regional governance and cooperation in climate change.

While these issues have been well analysed, an overlooked consequence of this persistent fragmentation is the lack of interpersonal connections between South Asian youth. This is particularly pertinent given South Asia is one of the youngest regions in the world, with a median age of 26.8 in 2020, compared to 42.2 in Europe, 40 in East Asia, 38.3 in North America and 30.4 globally. Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal are even younger, with median ages of 25.3, 24.7, and 20.3, respectively. But limited educational mobility, due to divisions in the region, have hamstrung this once-in-a-generation demographic dividend. Academic experiences and opportunities for personal development and growth today hardly ever cross national boundaries.

Where schemes do exist, they tend to be focused on only one aspect of the issue. Initiatives like the South Asian University, Nalanda University (a revival of the Nalanda Mahavira), and the ‘BIMSTEC for Organised Development of Human Resource Infrastructure’ program aim to build centres of excellence that bring together people from across the region in one place. While these are commendable steps, they are only one part of the issue. We do not just need people to gather in one place — we need students to actively visit each other’s countries and foster a broader spirit of regional participation.

These current initiatives also lean towards being India-centric, given it is the largest and most influential actor in the region. This is where smaller countries can take a leadership role in putting the issue of student mobility at the top of the regional agenda. Nepal’s FY 2082/83 BS (2025/26 AD) budget cut fees for foreign student visas, which is an important first move in making Nepal a more accessible place for international education. The government could now seek to build on this step and take diplomatic efforts to spearhead a regional education initiative. Nepal should welcome South Asian students to study in its universities, and encourage Nepali students to spend time in other countries in the region.

Developing a South Asian Educational Mobility Scheme

Europe’s Erasmus program can be a guiding vision for a South Asian Mobility Scheme. The program was officially launched in 1987 to foster closer cooperation between universities across the continent through an organised system of student exchanges. Erasmus began with just 3,244 students in its first year and, in the four decades since, it has grown to encompass initiatives in training and sport with more than 16.7 million people having taken part in the broader program. Erasmus’ success is not only in its uptake, but the values of openness, collaboration, and the European identity it has promoted. The German political scientist Stefan Wolff has highlighted that it has created an ‘Erasmus Generation’ of citizens and leaders shaped by cross-border experiences, who have a distinct inclination towards cooperation and European integration.

South Asia can adopt these lessons to its own contexts. Right now, high costs for tuition and lodging, visa hurdles, credit recognition issues, and a lack of structured formal exchange agreements are the key constraints to student mobility. A regional framework for student exchanges, possibly funded through the creation of a Youth Fund based within one of the two main regional organisations — the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, or the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi–Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation — could be a driver for student mobility in South Asia and a foundation stone for further integration. Such a scheme could fund scholarships, semester exchanges, short-term immersion programs, summer schools, and language and cultural immersion programs. To be successful, governments would need to develop a framework to support partnerships between universities in the region, facilitate credit recognition and visa approvals, and minimise obstructive red tape. The initiative should also seek to ensure equitable access for students from all backgrounds, with an emphasis on marginalised communities.

There will of course be political and financial hurdles. But the costs of inaction are far greater. A regional youth program need not wait for the conditions to be perfect. An initiative can start small with pilot schemes that can be scaled up if they are shown to be successful. If governments show leadership and the political will to put forth an ambitious vision, businesses, philanthropists and civil society can be convinced to co-invest.

Making an investment in young people fosters regional connections and encourages business and innovation linkages. Social movements and political tensions are often downstream of people-to-people connections, which means that a generation of young people comfortable with each other and fluent in each other’s countries might be the first step towards resolving some of the political tensions in the region.

Conclusion

Imagine a world where Indian students spend time learning about Himalayan conservation in Nepal, Bangladeshi students visit Sri Lanka to learn about port developments, and Bhutanese students collaborate with their peers in Pakistan on taking advantage of the energy transition. This is a much better future for South Asia, and the world, than one in which the region’s young people grow up insulated, wary and suspicious of each other.

South Asian youth are already globally mobile, just rarely within their own neighbourhood. A South Asian Educational Mobility Scheme would revive historical traditions of cross–border learning in a modern spirit that lays the foundation for a shared future. In an environment of uncertainty and tension, there are few more powerful investments that a government can make than in its young people. It is their decisions, and the relationships they forge, that will shape the peace and prosperity of the region.

Rojan Joshi is an Economics and Finance student at the Australian National University, Canberra. He is interested in international economics and public policy, with experience across government, academia, think tanks and the private sector in Australia, India and Nepal.