Overview

A year ago, the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing lockdowns had severely impacted the Nepali economy, with the remittance sector among those affected. The negative balance of payments, declining exchange reserves, soaring inflation rate, and other depressing macroeconomic indicators had also pushed the central bank of Nepal, Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB), to direct all banks and financial institutions (BFIs) of the economy not to issue letters of credit (especially for the import of non-essential items like private vehicles) on 4 April 2022. Following this, the government also banned the import of 10 goods, that it deemed non-essential or luxury goods, in a bid to stop the country’s foreign reserves from further depleting. The ban was anticipated to be in place until mid-July 2022 and was met with criticisms from the private sector as well as other key stakeholders involved in export-import businesses.

During mid-April 2022, when these policies were adopted by the Government of Nepal, the foreign exchange reserves had amounted to NPR 1.17 trillion (USD 9.14 billion) (a 16.5% decrease from NPR 1.4 trillion in mid-July 2021) and the remittances had reached NPR 724.7 billion (USD 5.66 billion) (a 0.6% decrease from NPR 729.2 billion (USD 5.69 billion) in mid-July 2021).

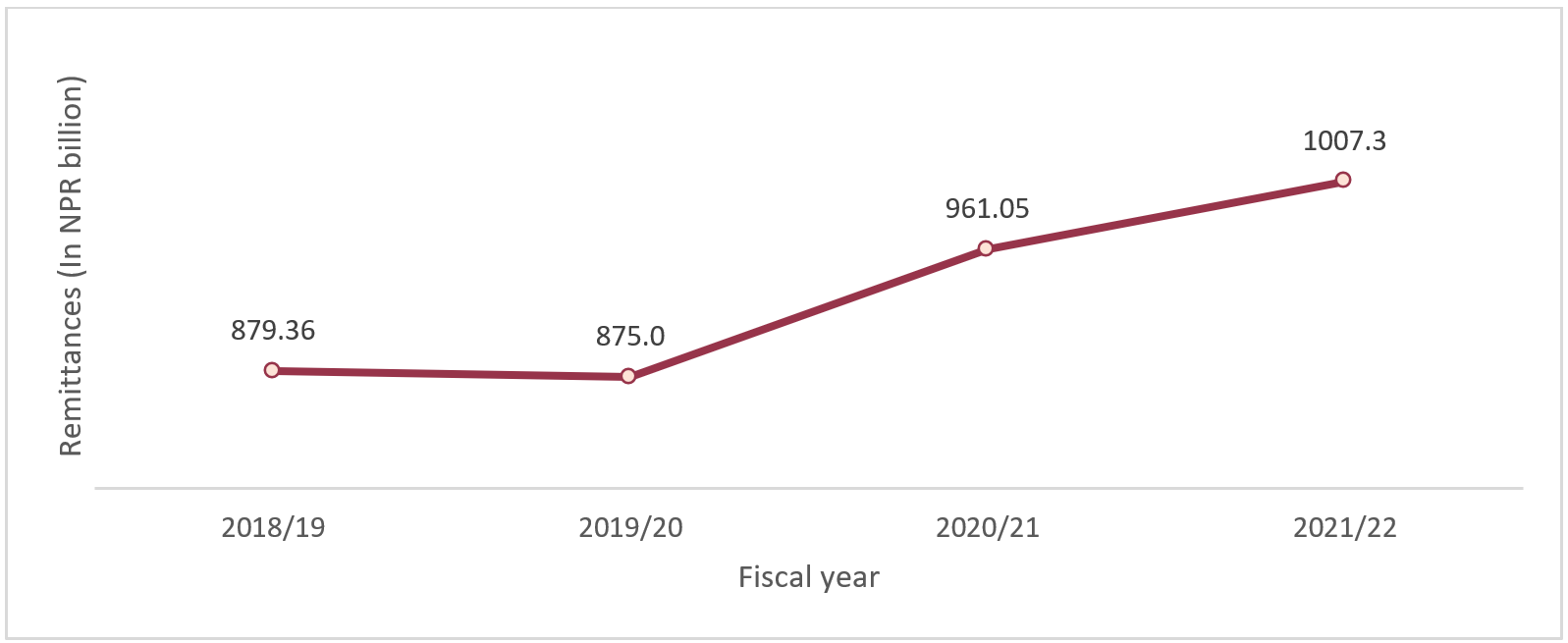

With the policies implemented since April 2022, the foreign exchange reserves were expected to deplete even more. The issue of depleting foreign exchange reserves could only be eased if the inflow of remittances would surge. Due to this reason, the recent 4.8% increase in remittances to Nepal, which reached NPR 1.007 trillion (USD 8.33 billion) in the final months of the FY 2021/22 compared to NPR 961.05 billion (USD 7.51 billion) in the corresponding period of the FY 2020/21, is encouraging and has provided relief to the Nepali economy.

Increase in the inflow of remittances to Nepal

The surge in remittances in FY 2021/22 is by a smaller percentage (4.8%), against a 9.8% increase in FY 2020/21. Despite this minimal increase, the amount reaching the range of trillions is worth notifying as it is significant and indicative of the gradual revival of the country’s migration sector, which had seen a temporary halt during the peak of COVID-19.

The remittance inflows to Nepal increased from NPR 87.1 billion (USD 0.68 billion) to NPR 92.4 billion (USD 0.72 billion) from mid-May to mid-June 2022 alone, which is a 6.12% increase from the previous month. A continued surge in the upcoming months can likely revive the country’s income. Figure 1 depicts the annual trend of remittance inflows to Nepal over the last four fiscal years.

Figure 1 Annual remittance inflows to Nepal in four consecutive FYs (in NPR billion)

Source: Current Macroeconomic and Financial Situation of Nepal (ending mid-July 2022)

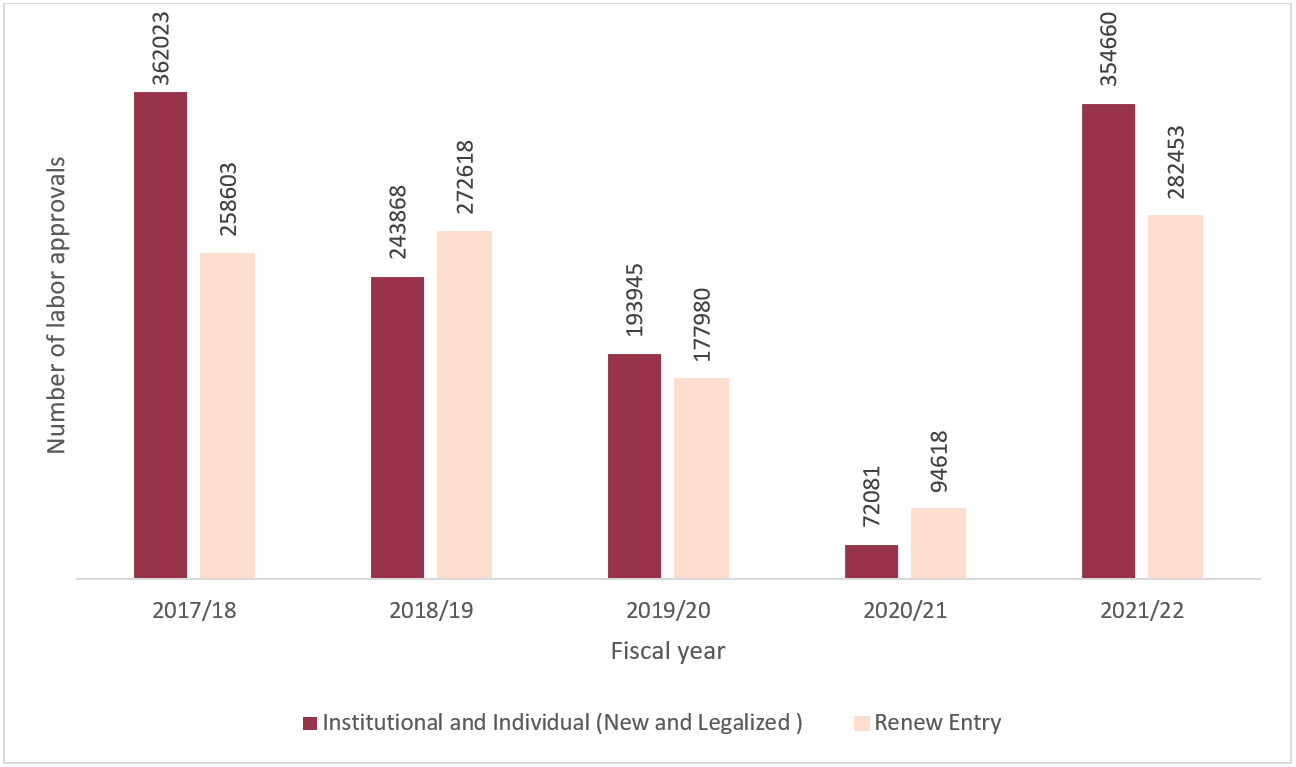

Encouragingly, the number of Nepali workers, including institutional and individual (new and legalized) workers, taking approvals for foreign employment also increased from 72,081 to 354,660 in the last month’s data of the FY 2021/22 (ending mid-July 2022). The increase signifies a whopping 392% jump from the previous year, majorly because of the relaxation of lockdowns and COVID-19 restrictions. Furthermore, increasing employment opportunities with increased salaries in destinations such as Malaysia, Qatar, India, and others also contributed to this positive trend. Likewise, the number of Nepali workers seeking renewed entry approvals increased by 198.5% to reach 282,453 in mid-July 2022, against a decrease of 46.8% in the previous corresponding period (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Annual number of labor approvals in the last five FYs

Source: Department of Foreign Employment

As per the annual data ending mid-July 2022, an increasing number of Nepali workers sought labor approvals for Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and United Arab Emirates (UAE) among many others. Table 1 shows the top 10 destination countries:

Table 1 Top 10 labor destinations of Nepali migrant workers in the last three FYs (institutional and individual – new and legalized)

| S.N. | Country | 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 |

| 1 | Saudi Arabia | 39279 | 23324 | 125374 |

| 2 | Qatar | 29835 | 22131 | 76822 |

| 3 | UAE | 52085 | 11611 | 53846 |

| 4 | Malaysia | 39167 | 106 | 25770 |

| 5 | Kuwait | 8974 | 2 | 22786 |

| 6 | Bahrain | 3305 | 3146 | 7592 |

| 7 | Romania | 1930 | 1954 | 6423 |

| 8 | South Korea* | 3542 | 16 | 4253 |

| 9 | Oman | 1996 | 1556 | 3627 |

| 10 | Cyprus | 1447 | 1003 | 3222 |

*Including EPS

Source: Department of Foreign Employment

However, India, which is unaccounted for in the official data, remains one of the largest migration destinations for Nepalis living in the border regions of the neighboring country.

Addressing barriers to remittance sector that prevents economic development

Despite these encouraging figures on the number of remittances and migrants seeking employment abroad, the two factors continue to be obstructed by barriers that prevent remittances from aiding Nepal’s economic growth.

One of the most critical barriers is the high cost of sending remittances. As per an article published in 2018, the average cost of sending remittances to Nepal was 4.7% which was below the global average of 7.1%. Likewise, the World Bank reported that the average cost stood at 4.54%, which was still well below the global average.

Similarly, the cost of sending domestic remittances is also high in Nepal. Elaborating this, if a person from Pokhara sends a remittance amount of NPR 10,000 (USD 81.91) to a person in another part of the country, for instance – Butwal, the remit companies charge at least NPR 100 (USD 0.819). Contrastingly, the maximum charge in a bank transfer amounts to only NPR 8 (USD 0.065) through connectIPS, a payment platform.

Hence, to address this issue in domestic remittances, NRB has set a transaction limit of up to NPR 25,000 per day from earlier NPR 100,000 in domestic remittances, as of 2 March 2022. The goal of establishing this threshold was to deter people from using remittance intermediaries and to encourage them to send money via banking institutions or connectIPS, that are formal and digital methods. The aforementioned regulation, which narrows the scale for domestic remittances, is also consistent with the NRB’s policy commitments to promote greater financial literacy and discourage the use of remittance intermediaries at the national level, both of which were mentioned in its mid-term review of Monetary Policy 2078/79.

Although, as of mid-July 2022, it has been reported that domestic remittances have increased significantly as a result of the directive to set the threshold limit. However, hundi/illegal operators are still using the F1 Soft payment gateway to transfer money from foreign marketplaces, indicating the lingering presence and the grasp of informal channels that exist in Nepal, further obstructing economic development that is achieved from remittances.

Way forward

Even before the pandemic, the remittance sector of the Nepali economy was undergoing policy hurdles. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the challenges have been exacerbated, indicating the need for a more holistic approach to addressing policy challenges. Dialogues between the Embassy of Nepal in various destination countries with the Chamber of Commerce and Industries of the respective destination countries as well as with the trade and investment boards should be encouraged and instituted as a frequent event. Through these programs, the formalization of the remittance channel can be promoted, a larger population can be informed and made aware, and opportunities for investment or employment can be explored.

When such avenues are identified, skill development programs aimed at supporting the skilling, re-skilling, and up-skilling of migrant workers can be targeted and planned in collaboration with donor agencies, national and international organizations, the private sector, civil society groups, and other key stakeholder groups. The British Council-managed “Dakchyata: TVET Practical Partnership” program of NPR 265.24 million, which is intended to be in operation for 10 months and serve at least 1,500 returnee migrant workers, is one of the most recent examples of such skill development programs. The Nepali economy may benefit, if the skill gaps are identified and prioritized in this manner.

Though the rise in remittance inflows, labor approvals, and salary increases are commendable, they will only give the Nepali economy a temporary respite. Unless the barriers are eliminated, structural transformation cannot be accomplished. Nepal’s external sector is still fragile and needs to be handled promptly. Given this, the Nepali economy would suffer due to a shortsighted approach to solving a deep-rooted problem. It is necessary to investigate and put into practice a more sustainable policy approach with better and more efficient plans and policies that can lower the cost of remittances, boost the use of formal channels, and strengthen productive investments in the nation.

Nasala Maharjan is a Bachelor's in Business Administration (BBA Honors) graduate from Kathmandu University with a major in Finance. She is mostly interested in researching and writing about economic development and contemporary issues in Nepal. She joined Nepal Economic Forum (NEF) as a Research Fellow in 2019 and is currently a beed at beed management.