- Introduction: Nepal’s Evolving Economic Structure

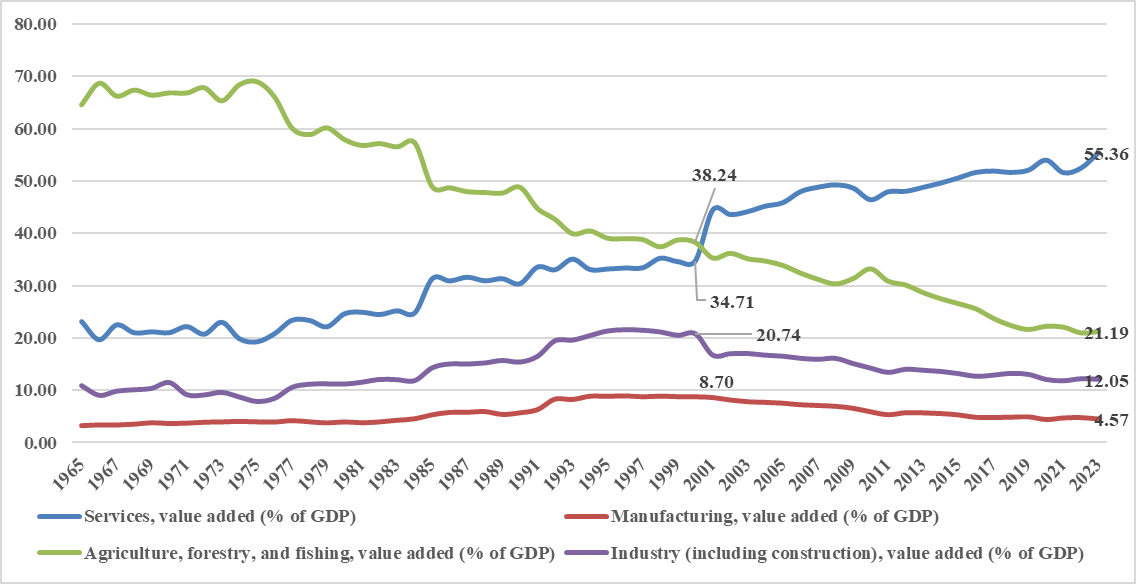

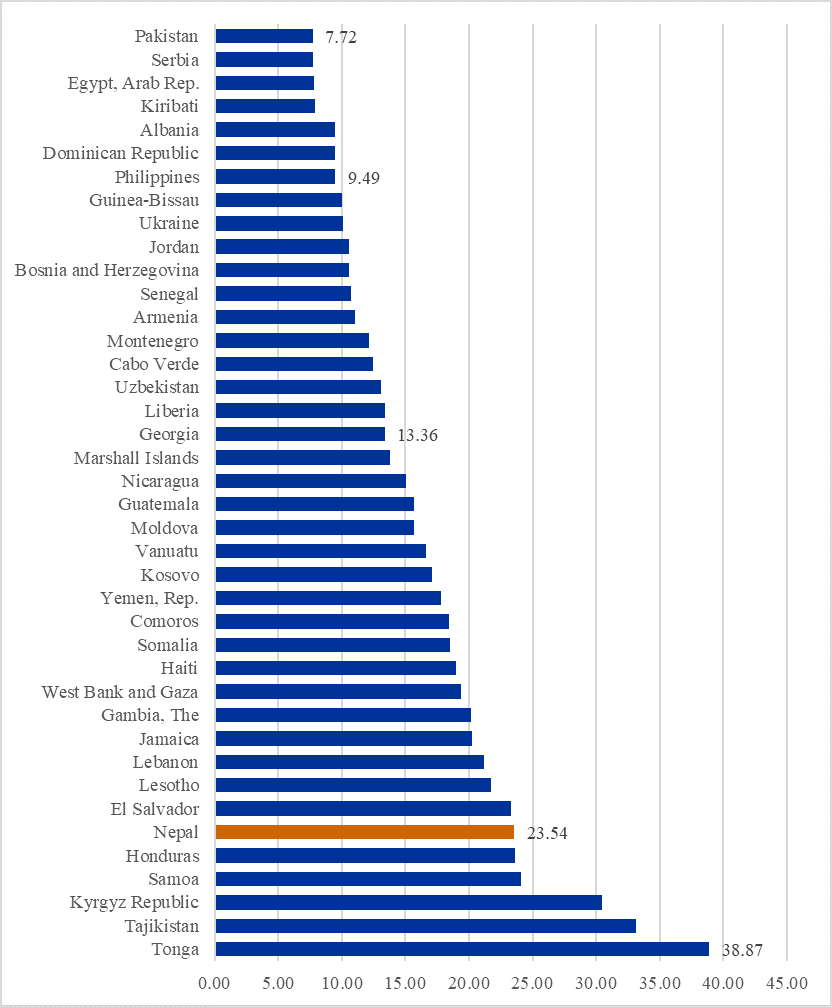

As of 2023, Nepal’s economy is mainly focused on services, which account for about 56% of the country’s GDP. Agriculture contributes 21% while industry makes up only 12% (Figure 1). As Nepal is highly reliant on external sources of finance for its socio-economic development, with personal remittance inflows consistently exceeding 25% of GDP (Figure 5), the country is experiencing a structural shift from an “agriculture-based subsistence economy” to a “remittance-based consumption economy”. However, about 4.13 million households (roughly 62% of all households) are engaged in agriculture-related activities. This highlights the persistent dominance of low-productivity employment in rural areas and the limited transformation of the agricultural sector. This duality between a service-dominated GDP structure and agriculture-dependent employment reflects Nepal’s incomplete and uneven structural transformation.

If we look at structural breaks of key macroeconomic indicators of Nepal, considering the period after economic reform and liberalization of the mid-1980s to the outbreak of COVID-19, a series of persistent disruptions challenged Nepal’s economic trajectory. Major economic disruptions took place between 2000 and 2003, when the internal armed conflict intensified and the royal massacre took place. These challenges emerged in the aftermath of liberalization policies introduced in the mid-1980s and were worsened by the decade-long armed conflict (1996–2006) and prolonged political transitions. During this time, a growing disparity emerged between regular government spending and investments in infrastructure. Although remittance inflows increased significantly, trade deficits widened, and public investment capacity in terms of capital expenditure weakened. The financial sector expanded in terms of access and financial services; however, it remains constrained by inefficiencies, limited depth, and poor intermediation quality. The banking sector continues to dominate financial intermediation, but capital market development has been slow, with limited product offerings, low investor participation, and weak institutional depth. This imbalance reflects a financial system that is expanding in size but lagging in quality, efficiency, and inclusiveness.

According to the classical developmental theory, countries normally transition from agriculture to industry and then to services. However, Nepal bypassed significant industrial growth, with workers moving directly from agriculture to foreign employment or in the domestic service sector. Nepal’s shift from agriculture to services without significant industrialization exemplifies premature de-industrialization. This type of premature de-industrialization, combined with ongoing political instability, has obstructed the necessary economic changes for consistent long-term growth. Figure 1 illustrates the evolving sectoral composition of Nepal’s economy as of 2023.

Figure 1. Structure of the Nepali Economy

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank

The current challenge lies in redirecting the economic structure away from remittance-driven consumption toward a productivity-based investment economy by expanding the industrial base and a high-value service sector. Reform 2.0 must serve as a comprehensive agenda to address these underlying issues, which are briefly discussed in this article.

- Structural Reform Issues

2.1. Narrow and Volatile Tax Base

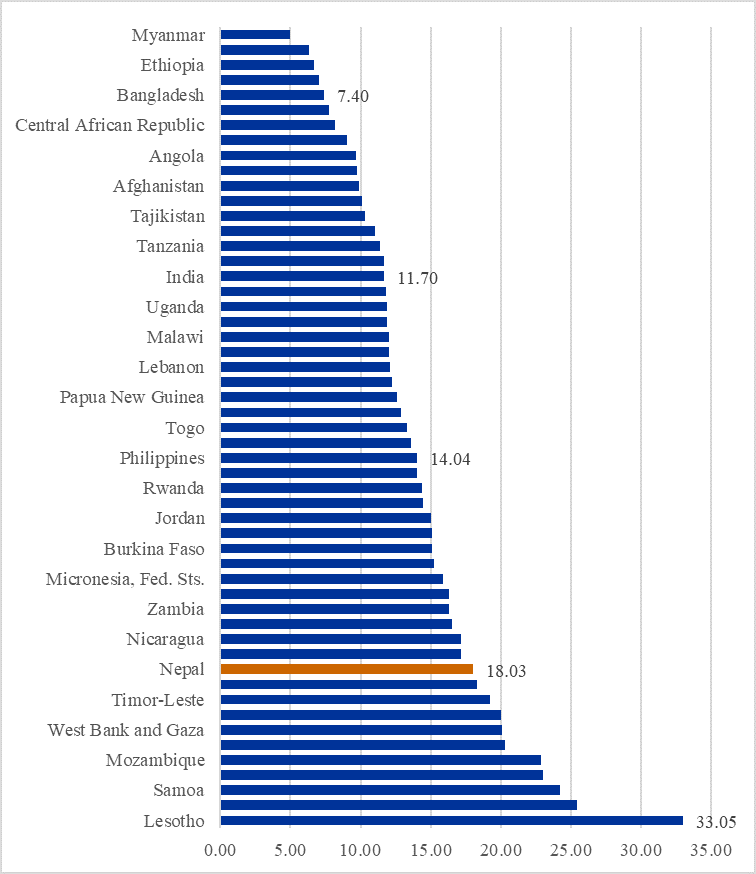

The tax system of Nepal is heavily reliant on indirect taxes, VAT, excise duties, and customs tariffs. While average annual tax revenue relative to GDP for the period of 2017 to 2021 ranks Nepal 11th among 53 low and lower-middle-income countries (Figure 2), the structure remains regressive and vulnerable to external shocks such as climate disasters or remittance disruptions. Widespread informality and low trust in institutions constrain tax capacity in many developing countries, including Nepal. Moreover, the dominance of the informal economy, limited tax compliance, and low trust in public institutions further complicate fiscal resilience.

Figure 2 shows the country’s relatively high tax revenue relative to GDP effort compared to its peers. However, reliance on indirect taxation can widen inequality and undermine the progressivity of the tax system. To improve taxation, it is important to broaden the tax base through digitization, targeting the informal and digital economy, simplifying tax structures, and enhancing public trust through transparent service delivery.

Figure 2. Tax Revenue (% of GDP): Average 2017-2021

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank

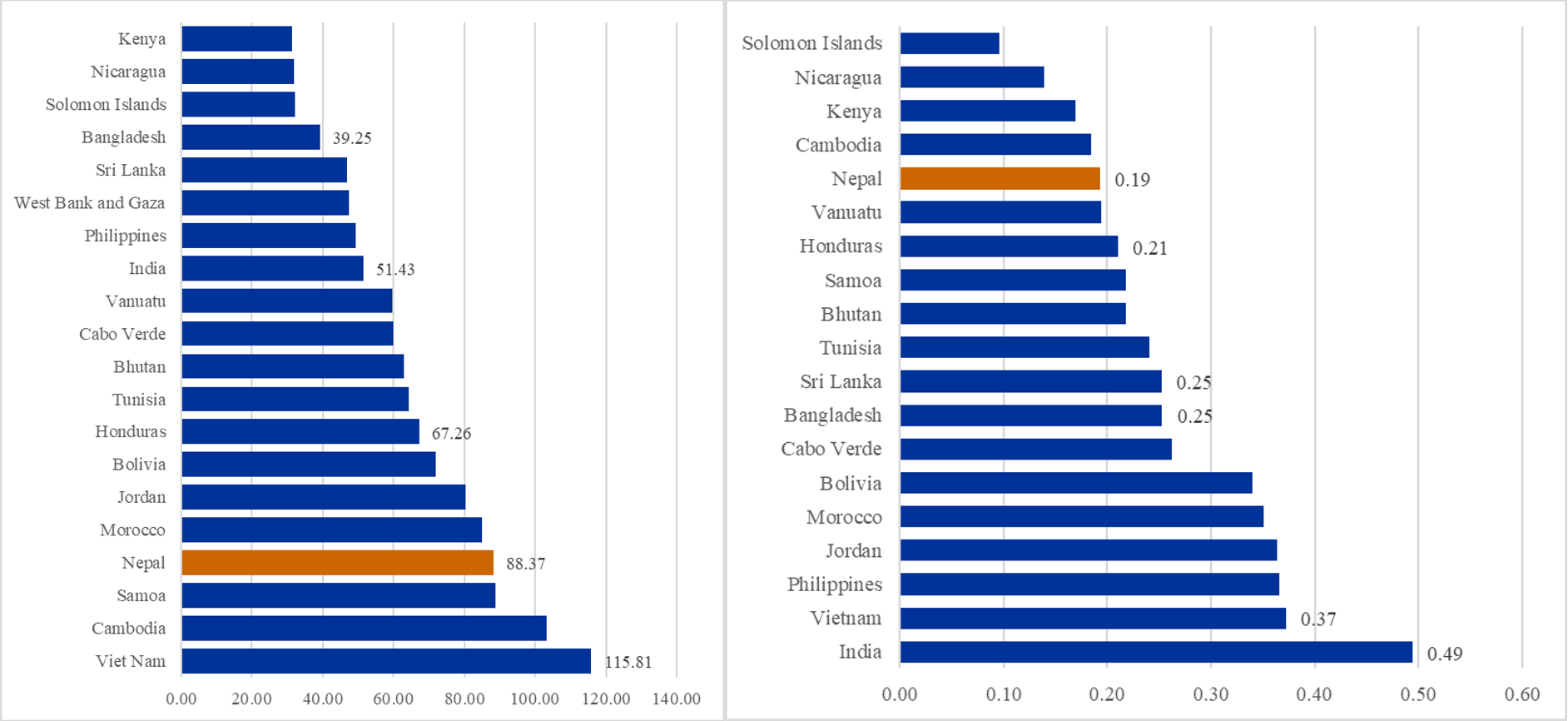

2.2. Underdeveloped Financial Market vs Over-Financing

Nepal’s financial system is primarily bank-based, and domestic credit to the private sector is almost 90% of GDP in recent years (Figure 3, Left Side). However, its financial development index remains low (Figure 3, Right Side), indicating an underdeveloped financial infrastructure and shallow capital markets. A significant portion of the credit is directed towards real estate and non-tradable assets, which fuels asset bubbles and reinforces wealth inequality. Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs), startups, and productive ventures often face a shortage of credit.

Figure 3 ranks the top 20 out of 68 low and lower-middle-income economies listed in World Development Indicators (WDIs) of the World Bank, where Nepal holds the 4th highest position in terms of the average domestic credit to private sector ratio to GDP for the period of 2018 to 2022. In contrast, Nepal ranks 5th lowest among these same 20 economies in the overall Financial Development Index developed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for the period of 2017 to 2021, which measures the depth, access, and efficiency of both financial institutions and financial markets. This disparity between Nepal’s high depth of financial institutions and its low score on the IMF’s Financial Development Index is largely due to inefficiencies in financial institutions and the underdevelopment of the capital market. Nepal’s capital market remains small and lacks depth, with limited listings and low sectoral representation. The absence of a well-functioning corporate bond market, a minimal yet fragile investor base, and a scarcity of diversified financial instruments hinder effective capital mobilization. Additionally, institutional and regulatory limitations restrict innovation and long-term financing, resulting in an overreliance on the banking sector and a lack of resilience in the broader financial system. To address these issues, reforms should focus on improving the quality of financial intermediation, deepening capital markets, introducing financial instruments such as government and green bonds, and expanding credit access to productive sectors. Economic growth and diversification are also necessary for the development of the financial market in the long run.

Figure 3. Domestic Credit to Private Sectors (% of GDP) vs Financial Development Index

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank & IMF Financial Development Database

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank & IMF Financial Development Database

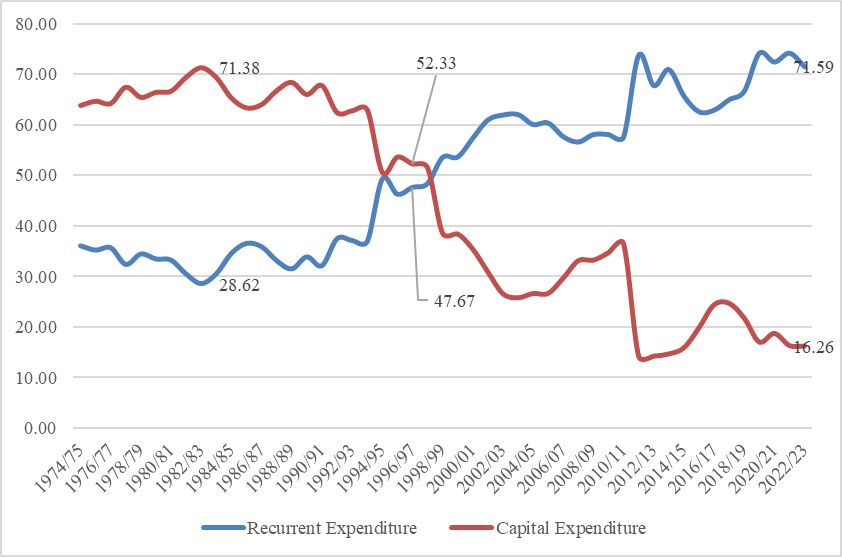

2.3. Imbalance in Government Expenditure

A structural imbalance exists between capital and recurrent expenditure. While capital budgets are underutilized, recurrent expenditures like wages, pensions, and subsidies consume a disproportionate share of resources. Federalism has compounded this issue through bureaucratic duplication. Figure 4 demonstrates how recurrent spending outpaces capital investment. Weak procurement systems, poor project design, and low absorptive capacity hinder development outcomes. Slow performance and limited size of the private sector have created spaces for over-reliance on the public towards public sectors, that have increased the size of government through recurrent expenditures. Nepal must adopt performance-based budgeting, control administrative overheads, and build institutional capacity, especially at the subnational level.

Figure 4. Share of Recurrent and Capital Expenditure

Source: Author’s compilation from NRB Reports

Source: Author’s compilation from NRB Reports

2.4. Inefficiency in Infrastructure Project Delivery

Despite having budget allocations, Nepal faces significant challenges in infrastructure delivery due to problems with land acquisition issues, weak contract management, and low technical capacity. Weak procurement systems and poor public investment management reduce infrastructure efficiency. These inefficiencies lead to increased business costs and limit connectivity and access to rural areas. To address these issues, reforms should focus on strengthening public investment management, ensuring transparent procurement practices, enabling one-stop clearances for major projects, and promoting public-private partnerships. Prioritizing infrastructure development is essential for improving productivity and attracting private investment.

2.5. Weak Industrial and Export Base

Nepal is currently facing significant challenges stemming from a weak industrial base. This situation is exacerbated by high production costs, policy uncertainty, and limited market access. The deindustrialization that occurred during the civil war from 1996 to 2006, coupled with a prolonged political transition until the adoption of the new constitution in 2015, has led to reliance on remittances for consumption and ongoing trade deficits.

To revitalize the economy, it is crucial to shift policy focus toward import substitution and export promotion. Key investments in Special Economic Zones (SEZs), industrial clusters, and Research & Development (R&D) are essential. Additionally, reducing labor and logistics costs is critical for rebuilding a competitive industrial base. The private sector needs to build confidence in these strategies to effectively promote import substitutions and export growth, ultimately transforming the overall economy.

2.6. Labor Market Rigidity, Outmigration, and Remittance Dependency

Nepal’s labor market is marked by rigidity, informality, and a significant skill mismatch. Many young individuals entering the workforce lack employable skills, and there is limited creation of formal jobs. As a result, millions of Nepalis seek work abroad, leading to a dynamic labor force beyond national borders. Consequently, remittances account for nearly 25% of GDP on average in recent years. Figure 5 ranks Nepal 6th among 120 low and lower-middle-income economies regarding the average remittance inflows ratio to GDP for the period of 2018 to 2022. While remittances contribute to poverty reduction, they also highlight failure in domestic job creation and create a long-term dependency on foreign employment. Heavy reliance on remittances has shaped the consumption-driven growth in many South Asian economies, including Nepal, with long-term structural implications. To tackle these challenges, reforms are essential to strengthen technical education, enhance employment services, and support the reintegration of returnees. A robust industrial expansion, coupled with the development of a competitive and well-equipped private sector engaged in domestic production and merchandise trade, is essential for creating large-scale employment opportunities and reducing Nepal’s overdependence on foreign labor markets.

Figure 5. Personal Remittances (% of GDP): Average 2018-2022

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank

2.7. Energy Sector Inefficiencies

Nepal has harnessed only 2,800 MW of its estimated hydropower potential of 43,000 MW, technically and economically. As a result, power generation often exceeds the grid capacity, leading to seasonal energy waste. The sector faces challenges such as transmission bottlenecks, regulatory delays, and weak investment planning. To address these issues, a robust national energy strategy is essential. This strategy should connect power generation with industrial demand, improve transmission infrastructure, and encourage cross-border electricity trade. Additionally, integrating private sector investment and fostering regional cooperation is crucial for the sector’s development.

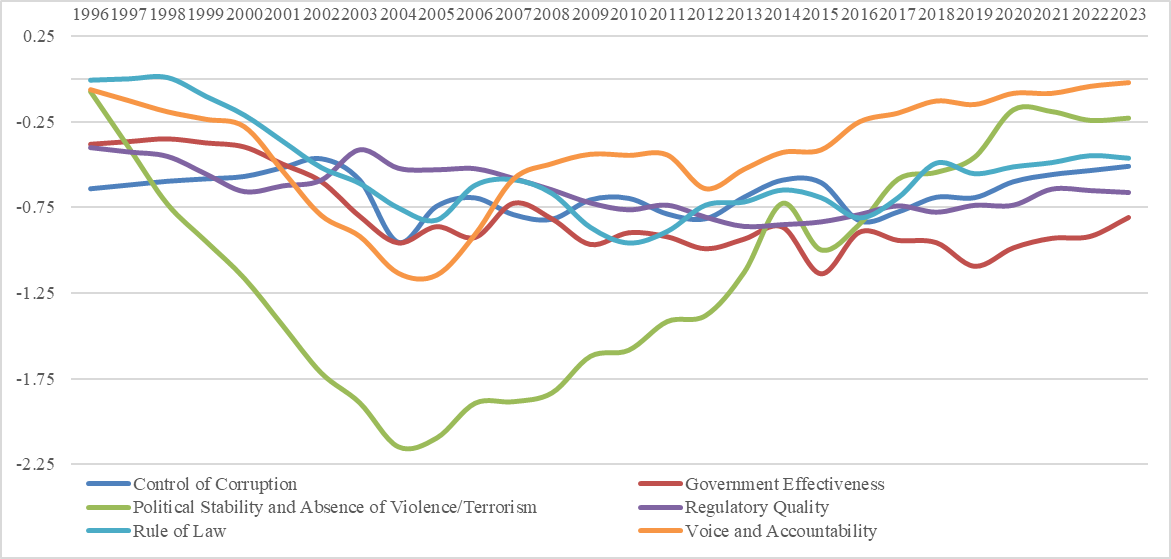

2.8. Governance, Corruption, and Regulatory Burdens

Governance remains Nepal’s most pervasive structural challenge. Weak institutional capacity, politicized bureaucracy, and systemic corruption collectively undermine effective service delivery, deter private investment, and erode public trust in state institutions. Figure 6 illustrates Nepal’s performance across six governance indicators from the World Governance Indicators (WGIs). Although political stability and civic freedoms, such as freedom of expression and electoral participation, have improved since the end of the internal armed conflict in 2006, there are still significant issues in other critical areas, including the rule of law, corruption control, and regulatory quality. These persistent governance weaknesses create uncertainty, reduce policy credibility, and stifle innovation and private sector dynamism. Improved governance and institutional quality are fundamental to enhancing macroeconomic resilience and achieving sustained long-term growth. For Nepal, building an accountable, transparent, and capable state is not merely an administrative necessity but a development imperative. Effective reform requires enhancing civil service professionalism, enforcing anti-corruption legislation, and embracing digital governance tools. Coordinated efforts across federal, provincial, and local levels are essential to ensure policy coherence and institutional effectiveness.

Figure 6. Institutional Quality Indicators (1996–2022)

Source: World Governance Indicators, World Bank

Source: World Governance Indicators, World Bank

- Reform 2.0 Agenda and Way Forward

In 2024, Nepal’s High-Level Economic Reform Advisory Commission unveiled a 447-page report detailing 408 reform actions. This Reform 2.0 blueprint spans financial, fiscal, business, energy, infrastructure, and public sector governance.

Key highlights include:

- Finance: Narrow interest corridors, issue infrastructure bonds, develop credit information systems, and enhance cooperative regulation.

- Fiscal Policy: Rationalize expenditure, shift from indirect to direct taxation, and improve budget transparency.

- Business Climate: Implement single-window systems, reduce compliance burdens, and promote FDI through legal reforms.

- Infrastructure: Improve capital budget execution and expand cross-border electricity infrastructure.

- Public Sector: Restructure underperforming SOEs, professionalize state enterprises, and rationalize public assets.

- Social Security: Raise senior citizen benefit eligibility from 68 to 70 to improve fiscal sustainability.

These measures are not just technical fixes; they aim to create a resilient, competitive, and inclusive economy. Successful implementation hinges on sustained political commitment, public accountability, and strong institutions. However, these measures alone are not enough to address the structural issues earlier.

- Conclusion

Nepal’s economic transformation has been shaped more by survival than strategy. The opportunity offered by Reform 2.0 is to reset this trajectory through deep, systemic reforms. Addressing structural issues in taxation, finance, labor, energy, and governance is crucial for building a more productive and equitable economy. To strengthen its institutions, Nepal must commit to reforming both policies and their implementation. The future of Nepal’s economy relies not only on external factors but also on the country’s commitment to addressing its internal structural challenges with vision, coherence, and determination.

Dr. Pradeep Panthi holds a PhD in International Development from Nagoya University, where he also served as a teaching assistant, in addition to a Master’s degree (with distinction) and a Bachelor’s degree in Business Studies from Tribhuvan University. He is currently working as a Research Fellow at the Policy Research Institute's Centre for Economic and Infrastructure Development Policy, having previously worked as a Consultant and Research Associate at the Asian Development Bank Institute. His experience includes managerial roles in banking and finance as well as academic positions in Nepal. Dr. Panthi's research interests encompass international finance, macroeconomics, development economics, and the dynamics of global capital flows, with a focus on economic development through trade, investment, and policy management.