The fashion industry has increasingly come under scrutiny for its role in polluting the environment, generating around 92 million tons of waste annually. It is expected to worsen and reach 134 million tons by 2030. While a good chunk of this waste is from clothing being burnt or sent to landfills, the very production of fabrics itself has adverse environmental impacts. Producing synthetic fabrics alone generates around 20% of the world’s wastewater. The ill effects of the current business model are reflected the best in graduating least developed countries (LDCs) in Asia. For instance, in Bangladesh, untreated wastewater from the clothing factories is discharged into various rivers, despite legal prohibitions, and it has damaged agricultural lands and caused skin sores in locals.

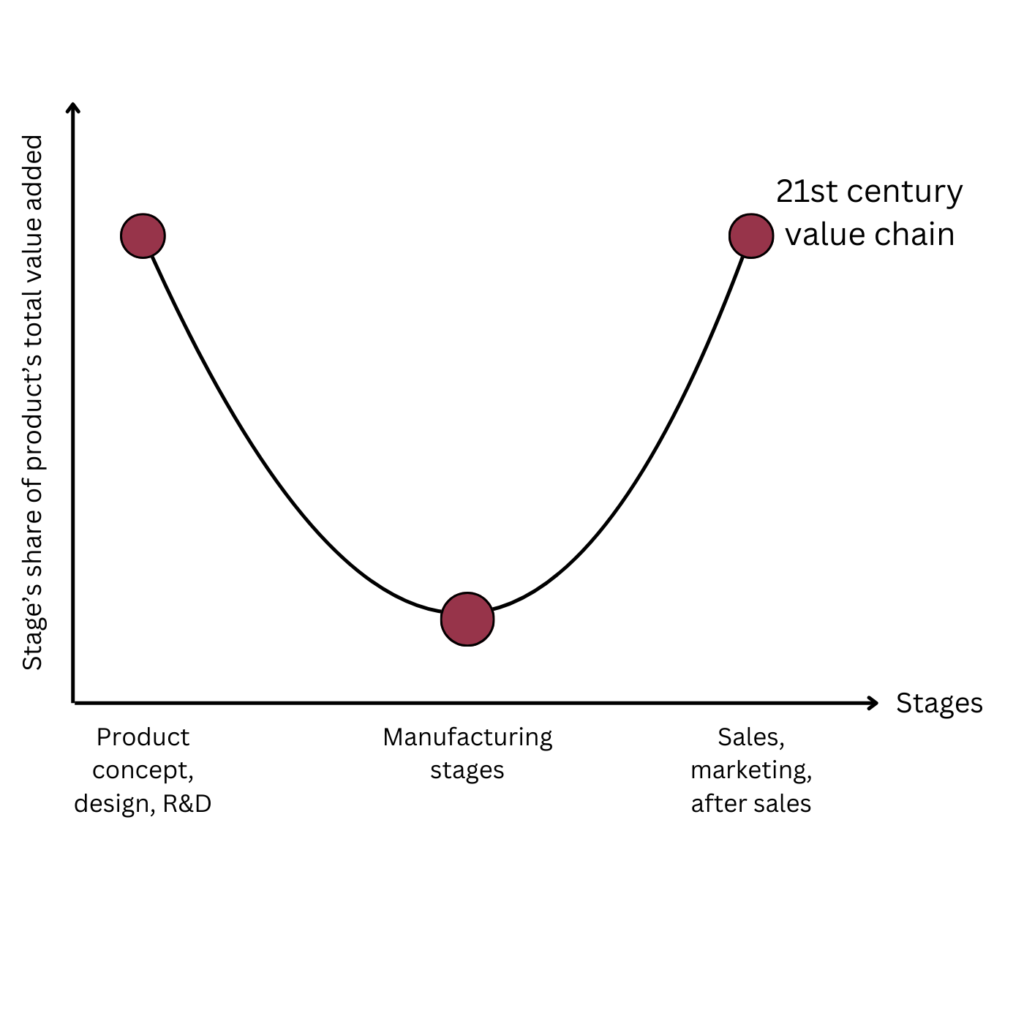

Figure 1. Value addition at different stages

Source: Adapted from World Trade Organization, 2022

Further, LDCs often do not develop sufficient backward linkages or create local value addition through sophisticated textile and fiber production. This causes them to not move beyond production, which adds the least economic value in the textile and apparel value chain, as depicted in Figure 1. With USD 65 billion worth of apparel exports being at risk due to increasing frequency and intensity of climate-related disasters, it is crucial for manufacturing LDCs to change business model and protect their local environment. This article will explore how Nepal could benefit from incorporating hemp in its textile productions in a sustainability and development context.

Sustainable Textile Options

There has been an increased consumer demand for sustainable practices and products as well as escalating regulatory attention, such as the European Union’s (EU) Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles. This has led to brands looking into how they can make their processes more sustainable. As a result, some have started incorporating low-impact fabrics into their lines. Among the various fabrics, hemp has gained prominence among sustainability circles, with the global hemp clothing market expected to reach USD 10.1 billion by 2028. An Patagonia, a United States outdoor clothing brand, that was named the United Nations Champion of the Earth in 2019 for its sustainability-centric business model. It has been using hemp in its products since 1997, sourcing it from China. Following the passage of the 2018 Farm Bill, which legalized hemp production and transport across the United States, Patagonia has been working to revive the domestic hemp-fiber economy in Colorado, partnering with the government and soil scientists.

Hemp in Nepal

Nepal’s textile exports have been growing steadily over the past few months, even ranking as the fourth largest export item in FY 2022/23 at NPR 4.77 billion. Nepal has attempted to encourage the trend, including fabrics and textiles under the Nepal Trade Integrated Strategy 2023. However, this growth has been driven by synthetic yarn and fibers which are greatly polluting to the local environment. The current rising interest surrounding sustainability allows Nepal to explore environmentally friendly alternatives such as hemp.

Hemp is native to Nepal and grows in several districts in the western regions, at upper-middle altitudes of 1,500 – 3,500 meters. Before the ban in 1973, reportedly ‘a large amount of land in the central, western and far western regions’ was dedicated to growing cannabis. Currently, there are no farms dedicated solely to hemp, and they coexist in fields with other grains. Due to the ambiguous laws surrounding hemp cultivation, many harvest the plants that have grown in the wild. Furthermore, existing hemp goods dealers use imported hemp fiber from China due to the scattered nature of the value chain and the lack of quality control. However, there has been growing debate in Nepal about regulating and managing cultivation to boost exports and employment. Entrepreneurs have been calling attention to the economic potential that hemp holds, underlining its popularity among foreigners.

What is There to Gain?

Alongside being increasingly favorable in sustainability-focused apparel demographics, hemp has the added advantage of not depleting the local environment it is grown in. Starting at the soil, its deep root system helps prevent soil erosions and makes the plant drought-resistant by letting it access deep soil water. This makes it attractive to Nepal with a steep hillside geography and challenging irrigation. Furthermore, hemp has also been shown to encourage better soil health by cleaning contaminated soil without negatively affecting the plant much. It extracts heavy metals, such as lead, cadmium, and nickel, from contaminated soil.

Hemp is also considered to be a fast-growing high-yield crop. Accounting for the cost of agricultural activities such as fertilization, cultivation, irrigation, and fiber yield, hemp produces three times more metric tons of fiber per hectare cultivated, compared to cotton. Alongside having a higher yield per hectare, it also is a more sustainable option due to using less water. An estimated 9,758 liters of water is required for one kilogram of cotton, whereas hemp requires around 2,400 to 3,400 liters per kilogram. This means that hemp could be grown at a fraction of the agricultural costs associated with growing cotton, while greatly reducing the risks of microplastic pollution associated with synthetic materials, even recycled polyester.

Reviving the hemp trade would also have socioeconomic benefits. Prior to the US-induced ban on cannabis, hemp played an integral role in sustaining many rural communities in Nepal. The haphazard blanket ban caused hardships for hemp farmers, pushing many into poverty. Industrial hemp cultivation would create more stable employment for rural farmers and also open opportunities for training and modernizing the hemp agricultural sector. Furthermore, being able to institutionalize industrial hemp would preserve traditional crafts and offer local artisans an avenue to enter the global marketplace.

What Needs to be Done?

Despite all its pros, Nepal does have significant barriers it needs to overcome in the context of the hemp trade. The biggest one would be the stigma against hemp as a member of the Cannabis sativa plant species. It makes it crucial for legislation to clarify the difference between hemp and marijuana according to their usage and their chemical makeup. Hemp contains tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) of around 0.3% or less and is not used to produce narcotics, whereas marijuana can have a THC content of up to 20%. Accordingly, there also needs to be proper implementation and control measures for requirements industrial hemp needs to fulfil and for proper disposal mechanisms for crops exceeding the 0.3% limit. Hemp enterprises could also lean into the promotion of hemp as a sustainable material with historical ties to local communities in the country to overcome the stigma.

Hemp’s underdeveloped value chain is another barrier preventing Nepal from tapping into its industrial potential. Globally, Nepal would be competing with well-established and advanced exporters such as China. This makes it strong linkages between value chain actors, such as collectors, processors, traders, manufacturers, and exporters pivotal for hemp to be competitive. Lessons on an inclusive value chain can be taken from a similar initiative developing a value chain for nettle or allo in Naugad Rural Municipality. Key interventions included strengthening local institutions for higher efficiency and strengthening private sector linkages for better market access — factors which are crucial for hemp to succeed.

Furthermore, stakeholders should also be mindful of the cultural ties that locals and village communities could have with hemp when planning the value chain. Seeing positive outcomes for a product that has been disregarded and even discouraged for the past few decades will require time, patience, and united efforts. However, it will be such ground-level interventions that will better the lives and livelihoods of disadvantaged groups and highlight indigenous or local Nepali products as sustainable alternatives.

Sukeerti Shrestha holds a Bachelor's degree in Business Administration (Finance) from Kathmandu University. She is passionate about development economics and sustainability, with a keen interest in community-inclusive policy making. Currently, she works as an Aspiring beed at beed Management, building on her prior experience in management consulting and social enterprises.